![Not Dead Yet]()

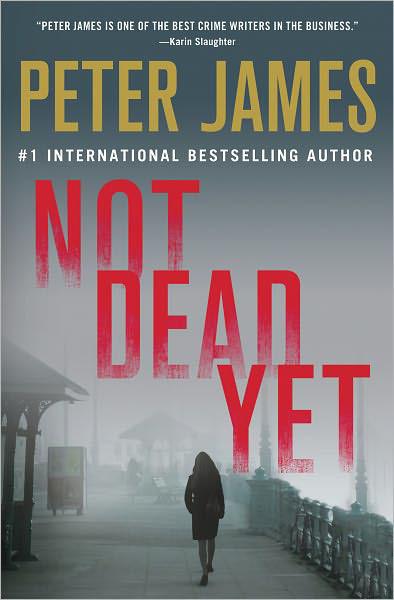

Not Dead Yet

head.’

‘Unlike the victim who doesn’t have that luxury,’ Potting interjected with a smug grin.

Ignoring him, Exton said, ‘I’m putting myself in the perp’s shoes. If I’m going to dismember my victim, why would I stop at cutting off his head and limbs, and leave his torso intact? Why not cut everything into little pieces? Much easier to dispose of.’

‘What about someone who has a grudge against the farmer?’ Nick Nicholl said. ‘He doesn’t want to get caught, so he removes the head and hands, but puts the body there to try to frame the farmer?’

A possibility, Grace thought, but that didn’t strike him as likely. There were many kinds of murders, he knew from experience, but most of them fell into one of two categories: those cold psychopaths who planned carefully, and others who killed in the heat of the moment. The psychopaths who planned were the ones who often got away with murder. He remembered a conversation he’d once had with a Chief Constable some years back, when he had asked the Chief if in his experience he believed there was such a thing as the ‘perfect murder’. The Chief had replied that there was. ‘It’s the one we never hear about,’ he said.

Grace had never forgotten that. If someone devoid of all human emotion were to plan an execution killing, with the disposal of the body carefully thought out, he or she had a good chance of getting away with it. When you found a body, or body parts, that usually indicated carelessness by the killer. Carelessness tended to becaused by panic. Someone who had killed in the heat of the moment and had not thought it through.

This headless, limbless torso smelled of the latter to him. It was a hurried, amateurish body dump. When killers panicked, they made mistakes. And the kind of mistake a killer usually made was to leave a trail, however tiny. His job was to find it. Invariably, it involved getting his enquiry team doing painstaking work, turning every stone – and hoping, at some point, for that one small piece of luck.

He turned to the analyst, Carol Morgan. ‘I want you to look back through the serials covering the winter months – let’s set an initial parameter of February the twenty-eighth going back to November the first of last year – for any incident reported in the Berwick area. Someone behaving strangely, someone driving recklessly or just speeding; attempted break-ins; trespass. Take a three-mile radius around Stonery Farm as your starting point.’

‘Yes, sir,’ she said.

He let Glenn Branson run the rest of the briefing by himself. Although Grace kept track of all that was said, he was multi-tasking, running through the security strategy he had agreed with Chief Superintendent Graham Barrington, and which the Chief Constable had signed off. Gaia was arriving in this city the day after tomorrow. But he was also running through something that was happening tomorrow. Something he could not stop thinking about. The old rogue Tommy Fincher’s funeral. And one particular mourner who would be attending.

Amis Smallbone.

Just the thought of the creep caused Grace to clench his fists.

36

To those few people acquainted with Eric Whiteley, he seemed a creature of habit. A small, balding, mild-mannered man, with a wardrobe of inoffensive suits and dull ties, who was always unfailingly polite and punctual. During the twenty-two years since he had joined the Brighton firm of chartered accountants Feline Bradley-Hamilton, he had never taken a day off sick and had never arrived late. He was always the first in the office.

He would dismount his sit-up-and-beg bicycle at the New Road offices, directly opposite the Pavilion gardens, at precisely 7.45 a.m., rain or shine, with a tick-tick-tick sound as he scooted the last few yards balanced on one pedal. He would chain the machine to a lamp post which he had come to regard as his own, remove his bicycle clips, let himself into the premises and enter the alarm code. Then he would make his way up the staircase and along to his small back office on the second floor, with its frosted-glass borrowed-light window that was partially obscured by a row of brown filing cabinets and stacks of boxes. In winter he would switch on the heater, in summer, the fan, before sitting at his tidy desk, booting up his computer terminal, and settling into his tasks.

One thing his colleagues had learned about him was that he was something of a self-taught computer expert. He was normally able

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher