![Pilgrim's Road]()

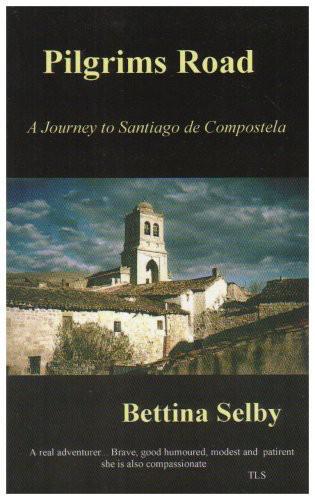

Pilgrim's Road

The previous year, she had got about a third of the way before being admitted to hospital with a serious chest infection. Her husband had to be sent for to take her home, and he had only agreed to her setting out again, she confided, because Eva, her niece, who was a student nurse, had agreed to come with her. But what had caused her to set her sights on Santiago in the first place I never really discovered. She was not religious in any accepted sense of the word, nor did she seem to be looking for answers to the great quandaries of human existence. She was not drawn by the marvellous church architecture on the route, nor was she a particularly athletic type who enjoyed the outdoor life for its own sake. She didn’t even like Spaniards very much, finding them far too noisy. ‘You wait,’ she said to me in a darkly conspiratorial whisper. ‘This lot haven’t even walked today, they’ll be talking and laughing until one or two in the morning, keeping us all awake.’ And yet even such blunt un-Christian remarks could not veil the essential attractive honesty and warmth which were her chief characteristics. When in fact the Spanish turned out to be totally inoffensive and to have retired to bed by ten o’clock, it was Sophie herself who pointed this out, and who castigated herself for her uncharitable remarks about them.

It was clear to anyone that Sophie was a woman of determination — headstrong some would call her. She had set out to achieve a particular goal, and she was going to keep at it if it took her a lifetime. Eva confided to me that her aunt suffered frequent bronchial attacks and was not strong. No one in the family expected her to succeed in getting to Santiago, she said, but no one could dissuade her from attempting it either.

When I wakened during the night listening to the small unfamiliar creaks and murmurs of the old buildings, I found I was thinking about Keats’ ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’. It had come to mind because of what Eva had told me about her aunt. The figures on the Grecian urn had been captured by the potter at the moment of reaching out towards some particularly desired thing; like the lover approaching his beloved. Keats sees this frozen intensity of passion that never reaches its goal as a blessed state:

‘... yet do not grieve... though thou hast not thy bliss, forever wilt thou love and she be fair.’

I thought that Sophie too would probably never quite achieve her goal, but that the urge to walk to Santiago would always be there, adding something special to her life, something big to look forward to, to plan for, to set out towards year after year. As many have discovered it is not the arrival that matters, but the journey itself.

6

Across Navarre

I N spite of the expectation of an effortless glide down the southern side of the Pyrenees — a delightful prospect for any bicycle traveller — I found myself reluctant to leave Roncesvalles the following morning. I was aware that I had come upon something special there, particularly during the previous evening’s mass, which I wasn’t too eager to lose.

The collegiate church of Roncesvalles is one of the most satisfactory settings that could be found for a pilgrim mass. For no matter how many times its walls have been rebuilt, they still enclose the spot from which for eight hundred years and more an unbroken stream of particularly heartfelt prayer has arisen. A traveller arriving cold and weary at Roncesvalles is extremely thankful for its existence, as I now knew from personal experience. But the gratitude of a modern traveller can be only a fraction of what medieval pilgrims felt. Don Javier told me that one of the chief duties of the monks of Roncesvalles (a duty continued to the present day) was to pray for the souls of the thousands of pilgrims who died on their way to Santiago. The bones of many who were never to reach St James’ Shrine lie in the underground ossuary beneath the funeral chapel at the gate, the victims of wolves, thieves, warring bands, or of the notorious mountain mists in which many pilgrims lost their way and perished of cold and hunger. This last hazard claimed so many victims that a bell used to be rung at Ibañeta in an attempt to guide them to safety. The worship and thanksgiving offered up by those who had survived all these dangers must have been especially fervent, and it would have been strange if this had not been reflected in the aura of the place.

From the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher