![Pilgrim's Road]()

Pilgrim's Road

over the Celtic West, though none was as distinctive as these in Galicia, nor have any others remained in use for quite so long, except perhaps the ‘black houses’ of the Hebrides. In Cebreiro a few of these pallozas are still in use, though I believe they are no longer shared by the livestock. As I stood there admiring them I had no idea I was to spend the night in one.

Satisfyingly strange and attractive though I found them, however, there would be pallozas in other places, while there was nowhere else on the entire route that had the unique attraction of Cebreiro’s church, and it was to this building that I now made my way.

A Benedictine monastery and a pilgrim hospice had been founded at Cebreiro as early as the ninth century, though it seems likely that the place had already acquired a special significance. At some point it became one of the rumoured resting places of the Holy Grail, and although scholars have advanced a score of different reasons for it, no one knows how or why this came about. The legend of the Holy Grail (the cup or chalice which Christ had used at the Last Supper) is one of the most mystical traditions to have arisen out of the relic cult and it was one that exerted a tremendous hold on the Christian imagination. The basis of the belief was that Joseph of Arimathea preserved the chalice, together with a few drops of the blood from Christ’s pierced side, and sailed away with it to seek a place of safe keeping. There are tales of the Holy Grail appearing in almost as many different sites as the wood of the True Cross, but the accounts are particularly concentrated in the Celtic West. Medieval romances, like the Arthurian legends, have the ‘Quest for the Holy Grail’ as their central theme, the ultimate prize which can be won only by the ‘perfect knight’ without stain or blemish.

An echo of the ardent and mystical beliefs surrounding the Holy Grail occurred again at Cebreiro in the thirteenth century, when the church became the celebrated site of a miracle. One bitter winter’s day a peasant had trudged far through the snow to hear mass, the only person to have braved the fearful weather. The officiating priest had sneered at him for making such an effort ‘just for a bit of bread and wine’. At this, the story goes, the elements became the actual body and blood of Christ, and a wooden statue of the Virgin on the adjacent wall turned her head towards the altar to witness the event. The miracle established Cebreiro as a site of pilgrimage in its own right, one of the most significant stops on the way to Santiago.

With all these tales of miracles and romance in my mind I came to the walled enclosure at the top of the village with the glebe field behind and the two small dark slate buildings. Even though I knew that both structures had been almost entirely rebuilt, my first thought was how ancient and absolutely right they looked with their dry-stone walling and simple dignity.

The monastery had begun to decline by the seventeenth century, and by 1960, when Don Elías Valiña, a local priest devoted to the pilgrimage, had started the work of restoration, the place was almost in ruins. What is there now is a great testimony to his efforts. The little hostelry has become a simple hotel, an unpretentious place with a log fire, long tables and benches, delightfully in keeping with the pilgrimage.

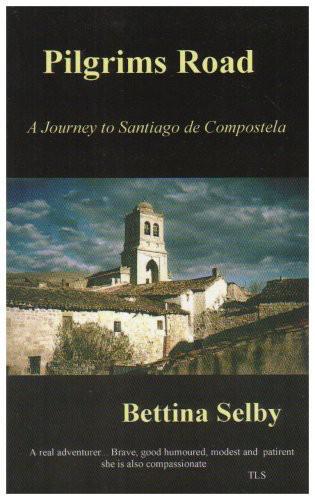

The church gives no hint of being rebuilt, and most authorities claim that the design can have changed little, if at all, from the original ninth-century structure. It is a modest three-aisled building, almost square, with a sturdy bell tower at one corner, the bells exposed in simple Romanesque arches. The interior walls have been left bare except for a statue of the Virgin — whether it was the very one whose head had turned in reverence I did not know. Nearby in a glass case is the twelfth-century chalice and patten, together with a reliquary for holding the preserved bread and wine of the famous miracle, given by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella when they came here on pilgrimage in 1486. There was a story that the royal couple had intended to take the divine elements with them, but they refused to be moved.

The chalice is exquisite, a masterpiece of the goldsmith’s art. But over and above the beauty of the vessels there is no doubt that the church gains an extra dimension by having them there, a visible link with their past. The objects themselves would also lose much of their

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher