![Pow!]()

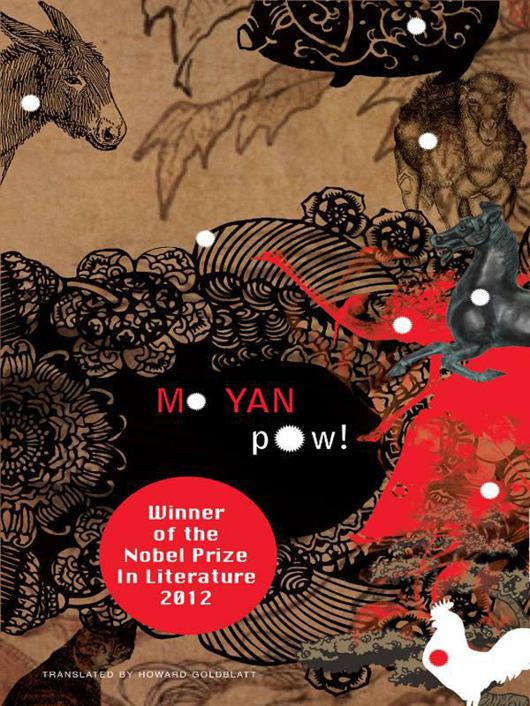

Pow!

them carefully, and I could imagine how the legendary Bo-le must have felt when he discovered a fine steed…‘Too bad,’ Father sighed, ‘what a pity.’ ‘Lao Luo, you can stop the phony dramatics,’ the cattle merchant snickered. ‘Do you want them or don't you? If not, I'll take them back with me.’ ‘No one's stopping you,’ replied Father. ‘Go ahead, take them.’ The cattle merchant gave an embarrassed little laugh: ‘We're old friends. If the goods die at the wharf, that's where they stay. You and I will be doing more business in the future…’

Yao Qi wore a pompous smile as he stood at the head of the line with the two handsome cows and I must say I was impressed. To be at the head of the queue he must have raced to the cow pens, forced halters onto the two most powerful animals and then walked them over, no easy task for someone that fat. That he had beat all those younger and stronger men to the first spot was testimony to the power of a man's will. The Luxi cows’ eyes were clear and bright and their muscles rippled beneath their satiny hides. They were in their prime, at an age when they could pull a plough with speed and power—a glance at their shoulders was proof enough. The West County cattle merchants were cattle thieves, part of an organized gang that stole cattle for others to sell. They had a special arrangement with the train station that promised a worry-free delivery of stolen cattle to our village. But things had begun to change. The cattle we bought from West County for the plant came not in cattle cars but in trucks, long semis covered with green tarps, gigantic, intimidating vehicles that could have been transporting anything, even military hardware. The animals emerged from the trucks on such unsteady legs you'd think they were drunk. The merchants were pretty unsteady too, and they were most certainly drunk.

Yao Qi entered the station with his Luxi cows, followed by Cheng Tianle, a one-time independent, conservative pig butcher. In the 1960s, butchers in our village began to skin the pigs they slaughtered because the hides were worth more, pound for pound, than the pork—they could be turned into fine leather. Cheng Tianle was the only one who refused to do so. He kept an oversized cook pot in his kill room, covered by a thick plank; the sides of the pot and the plank were covered with pig bristles removed the old-fashioned way. He'd cut a hole in one of the rear legs and open several passages with a metal rod, then put his mouth up to the hole and blow, puffing the carcass up like a balloon and creating a space between the hide and the flesh. Then he'd pour hot water over the skin causing the bristles to simply fall off. This method produced the best-looking meat; it was sold still enclosed in its shiny skin and looked so much more appealing than stripped pork. Blessed with powerful lungs, Cheng Tianle could inflate a whole pig with a single breath. His meat was popular with those who enjoyed the crunchy texture and appreciated the high nutritional value. But now, here he was, a man uniquely skilled to produce fine, crunchy meat by blowing air under the hide, looking as mournful as can be, leading two head of cattle into the building. It was as sad as putting a master shoemaker on a shoe assembly line. I'd always had a soft spot for him, a good and decent man who remained true to his ways. Unlike so many craftsmen who liked to show off in front of the young, Cheng Tianle, a modest man, treated me with kindness; he greeted me warmly whenever I dropped by in the old days and sometimes even asked if there was news of my father. ‘Xiaotong,’ he'd say, ‘your father is an upright man.’ And when I went to buy his bristles (I resold them to make brushes), he'd say: ‘You don't have to pay for those, just take them.’ Once he even gave me a cigarette. He never treated me like a child but always with respect. And I intended to repay his kindness within the limits of my authority.

Cheng Tianle led a big black local animal—it had a sagging belly that swayed from side to side, like a sack of ammonia. It was long past its working age, and either its owner or a merchant who specialized in old animals had fattened it up with hormone-laced feed. No good meat with high nutritional value could come from that. But the taste buds of the city-dwellers had deteriorated to such a point that they could no longer distinguish good meat from bad. There was no sense in giving them

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher