![Pow!]()

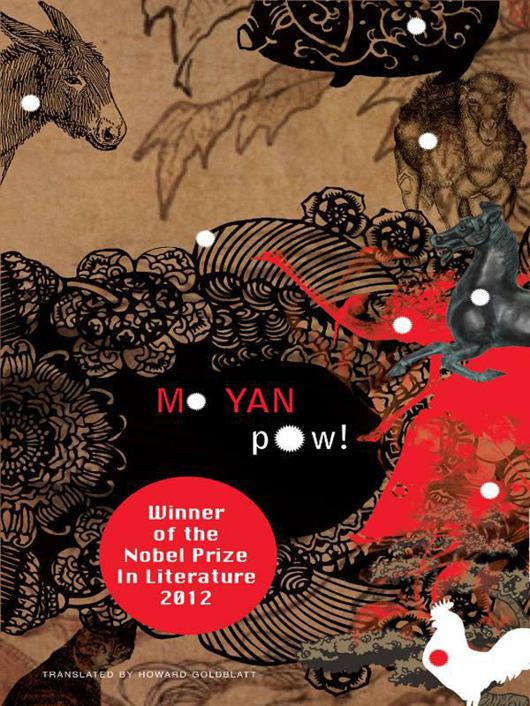

Pow!

competition was brutal, since the required test scores were so incredibly high .’ ‘ What do you know about the Wutong ?’ she turns to asks him, a mischievous grin on her face . ‘ Nothing .’ ‘ That's what I thought ’ ‘ So what is it ?’ he asks . ‘ No wonder the writer Pu Songling said “ After Wan's success with weapons, the area of Wu had no trouble with the remnants of the Wutong spirit ,’” she teases . ‘ Huh ?’ is all he can manage. She smiles . ‘ Forget it. But look here. She holds out her mud-stained hand. See ? The Horse Sprit is sweating .’ He takes her hand and leads her out of the temple. She turns to look back, reluctant to leave, and though she is looking at the idol, she's talking to me when she says : ‘ You should go to a hospital. You're not about to die but you do need some medical attention .’ My nose begins to ache, in part out of gratitude and in part over the vicissitudes of life. More and more people have joined the crowd outside, including the very old and the very young, bringing with them stools to sit on, assembling from both sides of the road and the cultivated fields behind the temple. What I find strange is that there isn't a single vehicle on the usually busy road, a departure that can only be explained if the police have cordoned it off. I wonder why they haven't erected the stage in the open field across the way instead of on the cramped temple grounds. Nothing is the way it should be, nothing makes sense. I look up and there's Lao Lan, his arm in a sling and a gauze bandage covering his left eye, looking like a defeated soldier, walking up to the temple from the cornfield behind us, escorted by Huang Biao. The girl they'd named Jiaojiao runs happily ahead of them, holding a fresh ear of corn she's just picked. Her mother, Fan Zhaoxia, cautions her : ‘ Slow down, honey, you could trip and fall .’ A middle-aged man in an undershirt, holding a folding fan and smiling broadly, runs up to greet the new arrivals : ‘ Boss Lan, how good of you to come .’ A man next to Lao Lan makes the introductions : ‘ This is Troupe Leader Jiang of the Qingdao Opera Troupe. He's a true artist .’ ‘ You can see why I can't shake your hand, Lao Lan says. My apologies ’ ‘ There's no need for you to apologize, General Manager. The troupe survives on your support ’ ‘ We help each other ,’ Lao Lan replies . ‘ Tell your actors to put on a good show to thank the Meat God and the Wutong Spirit. I offended the gods by firing a gun in front of the temple and got what I deserved ’. ‘ Don't you worry, General Manager, we'll sing our hearts out .’ Electricians with tool bags over their shoulders climb ladders to instal stage lighting, and watching them go up and down reminds me of the brothers who did electrical work back in Slaughterhouse Village years before. How things have changed. The surroundings are the same but not the people. I, Luo Xiaotong, have sunk to the lowest tier of society and am pretty well assured of never being able to turn my life round. My abilities do not extend beyond sitting in this dilapidated temple, propping up a body exhausted by the occurrence of what might have been an epileptic seizure and relating dusty old stories to a Wise Monk whose body is like rotting wood —

A large, gleaming purplish red coffin rested in Lao Lan's living room. In it lay a fancy urn full of bones. Why go to all that trouble? I wondered. But then Lao Lan knelt by the coffin and smacked it with his hand as he keened, and I got my answer. A hand on an empty coffin was the only way to create such a soul-stirring sound; only a grand coffin suited the sight of the imposing Lao Lan kneeling alongside; and only a coffin of that grandeur was capable of encapsulating the appropriately sombre atmosphere. I had no way of knowing if my conjectures were correct, because what happened later made me lose all interest in this train of thought.

I sat at the head of the coffin, draped in hempen mourning attire. Tiangua sat at the opposite end, similarly clad. A clay pot for burning spirit money had been placed in the space between us. She and I lit sheets of yellow paper embossed like money from the flame of the bean-oil lamp resting atop the coffin and fed them into the clay pot, where they quickly turned to white ash and swirls of smoke. The stifling heat of that lunar July day, coupled with the rope-belted hempen cloth I was swathed in and the fire in the pot

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher