![Pow!]()

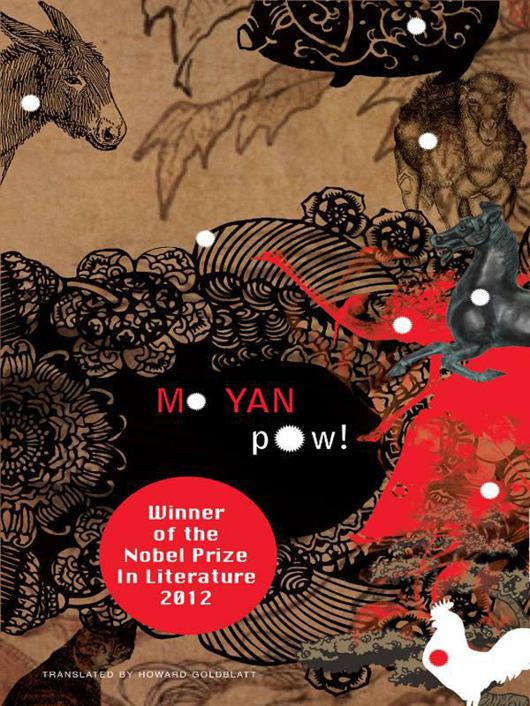

Pow!

were so tattered that we could see the abdomens of at least three of them. When the large wooden bell in Lao Lan's house was struck three times, Mother turned to Yao Qi. ‘Begin,’ she said.

From his position between the two tables, Yao Qi raised his arms like a conductor. ‘Begin, Shifu!’ he announced as he dropped his arms flamboyantly, thoroughly enjoying his moment as the centre of attention. It should have been me out there, but I was stuck inside, acting the dutiful son at the head of the coffin. Shit!

At Yao Qi's signal, two kinds of music erupted across the yard. On this side, the clap-clap of wooden fish and the clang of chimes and cymbals and the drone of chanted sutras. Along with that, a dirge with horns and woodwinds and flutes. A mournful sound indeed. As a murky dusk settled outside, the room grew dark, the only light a green sparkle from the bean-oil. I saw a woman's face in that light, and after staring at it for a few moments, I recognized it as Lao Lan's wife. Ghostly pale and bleeding from every orifice. ‘Look, Tiangua!’ I whispered, scared witless.

But she had dozed off, her head slumped onto her chest, like a chick resting against a wall. A chill ran down my spine, my hairs stood on end and my bladder threatened to burst, all good reasons to leave my post at the bier. Wetting my pants would surely be disrespectful towards the deceased! So I grabbed a handful of paper, threw it into the pot, jumped to my feet and ran out into the yard where I breathed in the fresh air before heading to the latrine next to the kennel and opening the floodgates with a shudder. The leaves on the plane tree quivered in the wind, but I could hear neither the wind nor the leaves, for both were drowned by the music and the chants. I watched the reporter taking shot after shot of the musicians and the monks.

‘Put some oomph into it, gentlemen!’ Yao Qi shouted. ‘Your host will show his gratitude later.’

Yao Qi's loathsome face glowed, a petty man intoxicated by his perceived glory. The same man who had once approached my father with a plan to bring Lao Lan to his knees was now his chief lackey. But I knew how unreliable he was, that he had the bones of a backstabber and that Lao Lan would be wise to keep him at arm's length. Now that I was out, I had no desire to return to the head of the coffin so, together with Jiaojiao, who had shown up from somewhere, I ran round the yard taking in all the excitement. She had gouged out the eyes of a paper horse and was clutching them like treasured objects.

As the music from the monks and musicians came to an end, Huang Biao's wife, who had changed into an off-white dress, pranced into the yard like an operatic coquette and placed tea services on both tables. Biting her lower lip, she poured the tea. After a drink of tea and some cigarettes, it was time to perform. The monks began by intoning loud, rhythmic chants, liquid sounds filled with devotion, like pond bullfrogs croaking on a summer night. The crisp, melodic clangs of cymbals and the hollow thumps of the wooden fish highlighted the clear voices. After a while the minor monks ended their chorus, leaving only the strains of the old monk's full voice, with its uncanny modulation, to mesmerize the listeners. Everyone held their breath as they drank in each sacred note emerging from deep in the old monk's chest; it seemed to send their spirits floating idly, lazily, into the clouds. The old monk chanted on for several moments, then picked up his cymbals and beat them with changing rhythms. Faster and faster, now throwing his arms open wide and bringing them back, now barely moving. The sounds changed with the movements of his hands and arms, heavy clangs giving way to thin chattering clicks. At the moment of crescendo, one of the cymbals flew into the air and twirled like a magic talisman. The old monk uttered a Buddhist incantation, spun round and held the remaining cymbal behind his back, waiting for its mate to drop from the sky atop it; as it landed it produced a metallic tremble that lingered in the air. A cry of delight rose from the crowd and the monk flung both cymbals skyward—they chased each other like inseparable twins and, on meeting, sent a loud clang earthward. As they descended they seemed to seek out the old monk's hands. The performance that day by the wise old monk, a Buddhist devotee of high attainments, left a lasting impression on every one of us.

Their performance ended, the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher