![Pow!]()

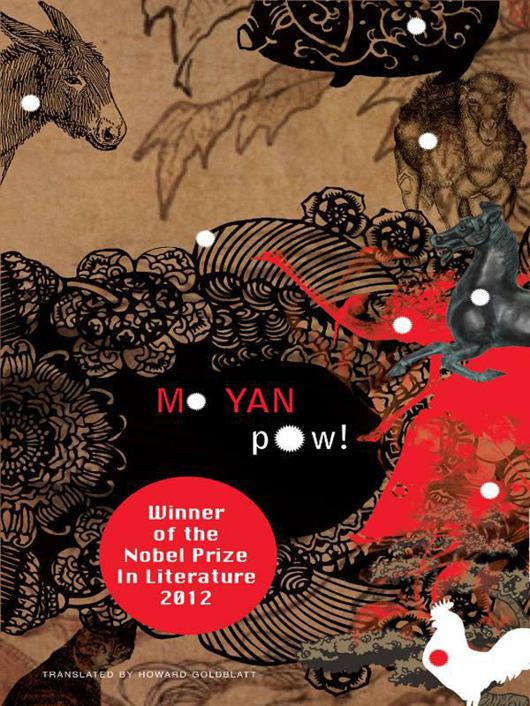

Pow!

farm labourer. That waste of money unleashed decades of humiliation upon Mother's family. His attempt to swim against the tide of history made my idiot grandfather a village laughing-stock. My father, on the other hand, was born into a lumpenproletariat family. He spent his youth with my good-for-nothing grandfather and grew up into a lazy glutton. His philosophy of life was: eat well today and don't worry about tomorrow. Take it easy and enjoy life. The lessons of history coupled with my grandfather's teachings made him the kind of man who would never spend only ninety-nine cents if he had a dollar in his pocket. Unspent money always cost him a night's sleep. He often counselled my mother that life was an illusion, everything but the food you put in your belly. ‘If you spend your money on clothes,’ he'd say, ‘people can rip them off your back. If you use it to build a house, decades later you're the target of a struggle.’ The Lan clan had plenty of houses but now they're a school. The Lan Clan Shrine was a splendid building that had been taken over by the production team to turn sweet potatoes into noodles. ‘Buy gold and silver with your money and you could lose your life. But spend your money on meat and you'll always have a full belly. You can't go wrong.’ ‘People who live to eat don't enter Heaven’ Mother would reply. ‘If there's food in your belly,’ Father'd say with a laugh, ‘even a pigsty is Heaven. If there's no meat in Heaven, I'm not going there even if the Jade Emperor comes down to escort me.’ I was too young to care about their words. I'd eat meat while they argued, then sit in the corner and purr, like that tailless cat that lived such a luxurious life out in the yard. After Father left, in order to build our five-room house, Mother turned into a skinflint; food seldom touched her lips. Once the house was built, I'd hoped she'd change her views on eating and let meat return to our table after its long absence. Imagine my shock when her scrimping grew worse. A grand plan was taking shape in her mind—to buy a truck, like the one that belonged to the Lan clan, the richest in the village. A Liberation truck, manufactured at Changchun No. 1 Automobile Plant, green, with six large tyres, a square cab and a bed as solid as a tank. I'd have preferred living in our old, three-room country shack with the thatched roof if that would have put meat back on the table. I'd have preferred travelling down bumpy rural roads on a walking tractor that nearly shook my bones apart if that would have put meat back on the table. To hell with her big house and its tiled roof, to hell with her Liberation truck and to hell with that frugal life which forbade even the smallest spot of grease! The more I grew to resent Mother, the more I longed for the happy days when Father was home. For a boy with a greedy mouth—like me—a happy life was defined by an unending supply of meat. If I had meat, what difference did it make if Mother and Father fought, verbally or physically, day in and day out? No fewer than two hundred rumours concerning Father and Aunty Wild Mule reached my ears over a five-year period. But what instilled a recurring longing in me were those three I mentioned, since meat figured in all of them. And every time the image of them eating meat blossomed in my head, as real as if they were right there with me, my nostrils would flare with its aroma, my stomach would growl, my mouth would fill with drool. And my eyes would fill with tears. The villagers often saw me sitting alone and weeping beneath the stately willow tree at the head of the village. ‘The poor boy! they'd sigh. I knew they'd misread the reason for my tears but was I incapable of setting them straight. Even if I'd told them it was the craving for meat that caused the tears, they wouldn't have believed me. The idea that a boy could yearn for the taste of meat until his tears flowed would never have occurred to them—

Thunder rolls in the distance, like cavalry bearing down on us. Some feathers fly into the dark temple, carrying the stink of blood, like frightened children, bobbing in the air and then sticking to the Wutong Spirit. The feathers remind me of the recent slaughter in the tree outside, and announce that the wind is up. It is, and it carries with it the stench of muddy soil and vegetation. The stuffy temple cools down, and more cinders fall out of the air over our heads, gathering on the Wise Monk's shiny pate and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher