![Pow!]()

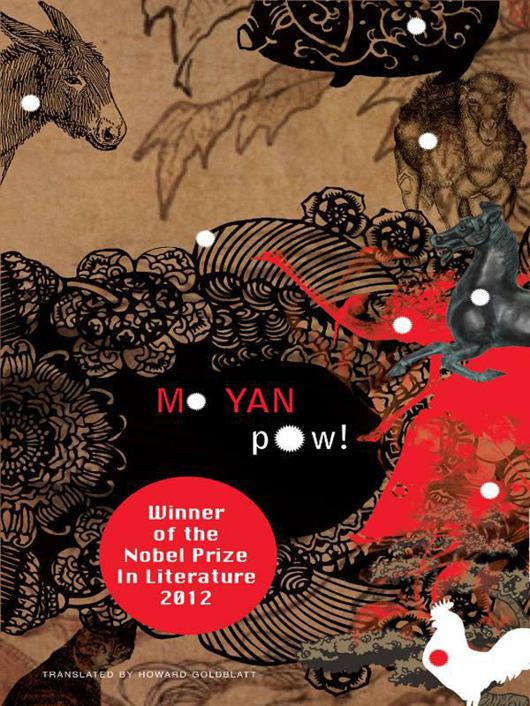

Pow!

on his fly-covered ears. The flies remain unmoved. Studying them closely for a few seconds, I see them rub their shiny eyes with their spindly legs. In spite of their bad name, they're a talented species. I don't think any other creature can rub its eyes with its legs and be so graceful about it. Out in the yard, the immobile gingko tree whistles in the wind which has grown stronger. As have the smells it carries, which now include the fetid stench of decaying animals and the filth at the bottom of a nearby pond. Rain can't be far off. It's the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, the day when the legendary herd-boy and the weaving maid—Altair and Vega—separated for the rest of the year by the Milky Way, get to meet. A loving couple, in the prime of their youth, forced to gaze at each other across a starry river, permitted to meet only once a year for three days—how tortured they must be! The passion of newlyweds cannot compare to that of the long separated, who want only to embrace for three days—as a boy, I often heard the village women say things like that. Lots of tears are shed over those three days, which are fated to be full of rain. Even after three years of drought, the seventh day of the seventh lunar month cannot be forgotten! A streak of lightning illuminates every detail of the temple interior. The lecherous grin on the face of the Horse Spirit, one of the five Wutong Spirit idols, makes my heart shudder. A man's head on a horse's body, a bit like the label of that famous French liquor. A row of sleeping bats hangs upside down from the beam above its head as the dull rumble of thunder rolls towards us from far away, like millstones turning in unison. Then more streaks of lightning, and deafening thunderclaps. A scorched smell pounds into the temple from the yard. Startled, I nearly jump out of my skin. But the Wise Monk sits there, placid as ever. The thunder grows louder, more violent, an unbroken string of crashes, and a downpour begins, the raindrops slanting in on us. What look like oily green fireballs roll about in the yard. Something like a gigantic claw with razor-sharp tips reaches down from the heavens and waits, suspended above the doorway, eager to force its way inside and grab hold of me—me, naturally—and then hang my corpse from the big tree outside, the tadpole characters etched on my back announcing my crimes to all who can read the cryptic words. As if by instinct, I move behind the Wise Monk, who shields me, and I am reminded of the beautiful woman who lay sprawled in the breach in the wall, combing her hair. Now there is no trace of her. The breach has turned into a cascade, and I think I see strands of hair in the cascading water, infusing a subtle osmanthus fragrance into the torrent…Then I hear the Wise Monk say: ‘Go on—’

POW! 2

My teeth were chattering. So cold! I buried my head under the covers and curled into a ball. Heat from the dead fire under the kang had long since disappeared, and the bedding was too thin to protect me from the icy concrete floor. Not daring to move, I wished I could turn into a cocooned bug. Through the bedding I heard the muffled sounds of Mother lighting the fire in the next room, the cracks of splitting firewood (that's how she vented her ire towards Father and Aunty Wild Mule). Why didn't she hurry and get the fire roaring?—that was the only way to drive the damp chill out of the room. At the same time I didn't want her to hurry because as soon as she had the fire going she'd try and get me out of bed. Her first shout would be relatively gentle; her second louder and higher and more annoyed. The third would be a bestial roar. A fourth had never been necessary, for if I hadn't rocketed out from under the covers on the third shout, she'd flick the covers off and whack my bottom with her broom. When it got that far, I knew I was doomed. For if, after the first painful whack, I jumped out of bed and onto the windowsill or scuttled out of range on the far side of the kang , she'd jump up without even taking off her muddy shoes, grab me by the hair or the scruff of my neck, press me down against the kang and really pound me with that broom. If I didn't try to get away or to resist, which she always took as a sign of contempt, her anger would boil over and she'd beat me even harder. However things progressed, if I was not on my feet by the third shout, my bottom and the poor broom were both bound to suffer. The beatings were

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher