![Praying for Sleep]()

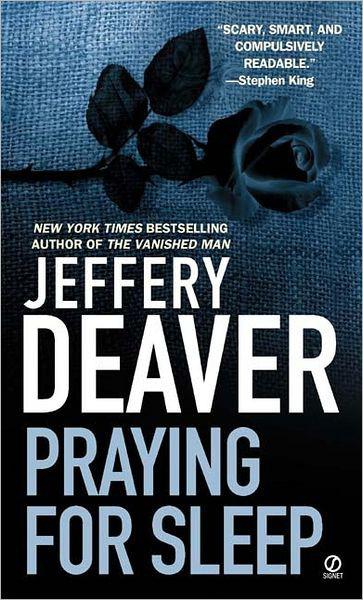

Praying for Sleep

his back. He then stripped off the regulation patent-leather belt and bound the officer’s feet. He stared in disgust for a moment, wondering if the trooper had gotten a good look at him. Probably not, he concluded. It was too dark; he himself hadn’t seen the cop’s face at all. He’d most likely figure that Hrubek himself had attacked him.

Owen ran back to his truck. He closed his eyes and slammed his fist on the hood. “No!” he shouted at the wet, breezy sky. “No!”

The left front tire was flat.

He bent down and noted that the bullet that had torn through the rubber was from a medium-caliber pistol. A .38 or 9mm probably. As he hurried to get the jack and spare, he realized that in all his plans for this evening this was something that he’d never considered—that Hrubek might be inclined to defend himself.

With a gun.

They stood side by side, holding long-handled shovels, and dug like oyster fishermen beneath the brown water for their crop of gravel. Their arms were in agony from filling and lugging the sandbags earlier in the evening and they could now lift only small scoops of the marble chips, which they then poured around the sunken tires of the car for traction.

Their hair now dark, their faces glossy with the rain, they lifted mound after mound of gravel and listened with some comfort to the murmuring of the car’s engine. From the radio drifted classical music, interrupted by occasional news broadcasts, which seemed to have no relation to reality. One FM announcer—sedated by the sound of his own voice—came on the air and reported that the storm front should hit the area in an hour or two.

“Jesus Christ,” Portia shouted over the pouring rain, “doesn’t he have a window?”

Apart from this, they worked silently.

This is mad, Lis thought, as the wind slung a gallon of rain into her face. Nuts.

Yet for some reason it felt oddly natural to be standing in calf-high water beside her sister, wielding these heavy oak-handled tools. There used to be a large garden on this part of the property—before Father decided to build the garage and had the earth plowed under. For several seasons the L’Auberget girls grew vegetables here. Lis supposed that they might have stood in these very spots, raking up weeds or whacking the firm black dirt with hoes. She remembered stapling seed packets to tongue depressors and sticking them into the earth where they’d planted the seeds the envelopes contained.

“That’ll show the plants what to look like, so they’ll know how to grow,” Lis had explained to Portia, who, being four, bought this logic momentarily. They’d laughed about it afterwards and for some years vegetable pinups had been a private joke between them.

Lis wondered now if Portia too recalled the garden. Maybe, if she did, she would take the memory as proof that going into business with her sister might not be as improbable as it seemed.

“Let’s try it,” she called through the rain, nodding toward the car.

Portia climbed in and, with Lis pushing, eased her foot delicately to the gas. The car budged an inch or two. But it sank down into the mud almost immediately. Portia shook her head and got out. “I could feel it. We’re close. Just a little more.”

The rain pours as they resume shoveling.

Lis glances toward her sister and sees her starkly outlined against a flare of lightning in the west. She finds herself thinking not about gravel or mud or Japanese cars but about this young woman. About how Portia moved to a tough town, how she learned to talk tough and to gaze back at you sultry and defiant, wearing her costumes, her miniskirts and tulle and nose rings, how she glories in the role of the urbane femme lover.

And yet . . . Lis has her doubts. . . .

Tonight, for instance, Portia didn’t really seem at ease until she discarded the frou-frou clothes, ditched the weird jewelry and pulled on baggy jeans and a high-necked sweater.

And the boyfriends? . . . Stu, Randy, Lee, a hundred others. For all her talk of independence, Portia often seems no more than a reflection of the man she is, or isn’t, with—precisely the type of obsolete, noxious relationship that she enthusiastically denounces. The fact is she never really likes these excessively handsome, bedroom-eyed boys very much. When they leave her—as they invariably do—she mourns briefly then heads out to catch herself a fresh one.

And so Lisbonne Atcheson is left to wonder, as she has

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher