![Praying for Sleep]()

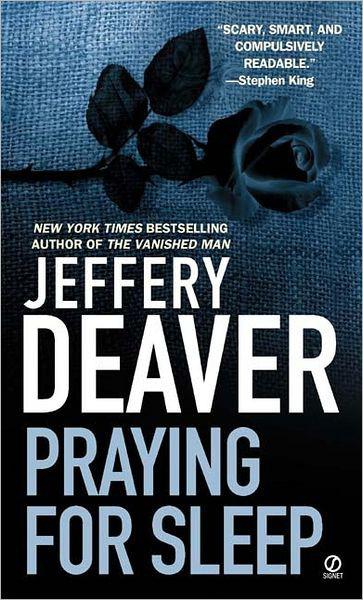

Praying for Sleep

walked away. He grabbed his old .22 pump rifle and walked out into the woods to plink cans and hunt squirrels and rabbits.

For several hours Lis was left alone with the distant pops of gunshots and the memory of the coldness in his eyes when he’d walked out the door.

And for several hours she wondered if she’d lost her husband.

Yet when he returned he was calm. The last he said about the nursery was, “I’d counsel against it but if you want to go ahead anyway, I’ll represent you.”

She’d thanked him but it was several days before his moodiness vanished.

Tonight, Lis started to tell her sister some of Owen’s concerns but Portia wasn’t interested. She simply shook her head. “I don’t think so.”

After a moment Lis asked, “Why?”

“I’m not ready to leave the city yet.”

“You wouldn’t have to. I’d do the day-to-day things. We’d get together a couple times a month. You could come out here. Or I could go into the city.”

“I really need some time off.”

“Think about it, at least. Please?” Lis exclaimed breathlessly to her sister’s face, pale and obscure in the darkness.

“No, Lis. I’m sorry.”

Angry and hurt, Lis picked up a large sandbag and tossed it onto the edge of the levee. She misjudged the distance though and it tumbled into the lake. “Shit!” she cried, trying to retrieve the bag. But it had slipped deep beneath the surface.

Portia spun some strands of hair once more. Lis stood. Several waves splashed loudly at their feet before Lis asked, “What’s the real reason?”

“Lis.”

“What if I said I didn’t want to buy a nursery. What if I was all hot for a boutique on Madison Avenue?”

Portia’s mouth tightened but Lis persisted, “What if I said, Let’s start a business where you and I travel around Europe and try out restaurants or rate châteaux? What if I said, Let’s start a windsurfing school?”

“Lis. Please.”

“Goddamn it! Is it because of Indian Leap? Tell me?”

Portia spun to face her. “Oh, Jesus, Lis.” She said nothing more.

The surface of the lake grew light suddenly, as a huge flash, bile green, filled the western horizon. It vanished behind a slab of thick clouds.

Lis finally said, “We’ve never talked about it. For six months, we haven’t said a word. It just sits there between us.”

“We better finish up here.” Portia seized her shovel. “That was some mean son-of-a-bitch lightning. And it wasn’t that far away.”

“Please,” Lis whispered.

A groan filled the night, and they turned to see the boathouse slide completely off the pilings and into the water. Portia said nothing more and started shoveling once again.

Listening to the chunk of the sandbags filling, Lis remained near the shore, gazing out over the lake.

As the boathouse sank, a vague white form appeared in the trees behind it. For a moment, Lis was sure that it was an elderly woman limping slowly toward the lake. Lis blinked and stepped closer to shore. The woman’s gait suggested she was ill and in pain.

Then, like the boathouse, the apparition eased off the shore and into the water, where it sank beneath the still, onyx surface. A piece of canvas tied to a cleat on the frame, or a six-mil plastic tarp, Lis supposed. Not a woman at all. Not a ghost.

She’d just imagined it. Of course.

The night Abraham Lincoln died, after spending many hours with a horrid wound in the thick mass of sweat-damp hair, the moon that blossomed out of the clouds in the eastern part of the United States was blood red.

This freak occurrence, Michael Hrubek had read, was verified by several different sources, one of whom was a farmer in Illinois. Standing in a freshly planted cornfield, 1865, April 15, this man looked up into the radiant evening sky, saw the crimson moon and took off his straw hat out of respect because he knew that a thousand miles away a great life was gone.

There was no moon visible tonight. The sky was overcast and turbulent as Hrubek bicycled unsteadily west along Route 236. It was a painstaking journey. He was now accustomed to the mountain bike and was riding as confidently as a Tour de France racer. Still, whenever a crown of light shone over the road before him or behind, he stopped and vaulted to the ground. He’d lie under cover of brush or tree until the vehicle passed then would leap onto his bike once again, his hammish legs pedaling fast in low gear; he didn’t know how to upshift.

A flash of light startled

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher