![Praying for Sleep]()

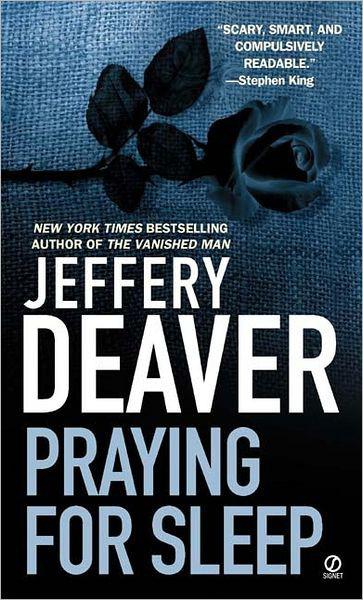

Praying for Sleep

wondering what exactly this meant, and why her sister seemed to treat it as an inevitable rite of passage.

What, Lis wondered, was life like when you “did” the city? Did Portia’s daytime hours pass quickly or slow? Did she flirt with her boss? Did she gossip? What did she eat for dinner? Where did she buy her laundry soap? Did she snort cocaine at ad-agency parties? Did she have a favorite movie theater? What did she laugh at, Monty Python or Roseanne ? Which newspaper did she read in the morning? Did she sleep only with men?

Lis tried to recall any time in recent years when she and Portia had spoken frequently. During the prelude to their mother’s death, she supposed.

Yet even then “frequently” was hardly the word to use.

Seventy-four-year-old Ruth L’Auberget had learned the hopeless diagnosis a year ago August and had immediately taken up the role of Patient—one that, it was no surprise to Lis, her mother seemed born to play. Her monied, Boston sous -Society upbringing had taught her to be stoic, her generation to be fatalistic, her husband to expect the worst. The role was, in fact, simply a variation on one that the statuesque, still-eyed woman had been acting for years. A formidable disease had simply replaced a formidable husband (Andrew having by then made his unglamorous exit in the British Air loo).

Until she got sick, the widow L’Auberget had been foundering. A woman in search of a burden. Now, once again, she was in her element.

Buying clothes for a shrinking figure, she chose not the shades she’d always worn—colors that made good backgrounds, beige and taupe and sand—but picked instead the hues of the flowers she grew, reds and yellows and emerald. She wore loud-patterned turbans, not scarves or wigs, and once—to Lis’s astonishment—burst into the Chemo Ward announcing to the young nurses, “Hello, dahlings, it’s Auntie Mame!”

Only near the very end did she grow sullen and timid—mostly at the thought, it seemed, of an ungainly and therefore embarrassing death. It was during this time that, on morphine, she’d described recent conversations with her husband in such detail that Lis’s skin would sting from the goose bumps. Mother only imagined it, Lis recalled thinking—as she’d protested to Owen tonight on the patio.

She’d just imagined it. Of course.

The chills, however, never failed to appear.

Lis had thought that perhaps their mother’s illness might bring the sisters closer together. It didn’t. Portia spent only slightly more time in Ridgeton during the months of Mrs. L’Auberget’s decline than she had before.

Lis was furious at this neglect, and once—when she and her mother had driven into the city for an appointment at Sloan-Kettering—she resolved to confront her sister. Yet Portia preempted her. She’d fixed up one of the bedrooms in the co-op as a homey sickroom and insisted that Lis and Ruth stay with her for several days. She broke dates, took a leave of absence from work and even bought a cookbook of cancer-fighting recipes. Lis still had a vivid, comic memory of the young woman, feet apart, hair in anxious streamers, standing dead center in the tiny kitchen as she slung flour into bowls and vegetables into pans, searching desperately for lost utensils.

So the confrontation was avoided. Yet when Ruth returned home, Portia resumed her distance and in the end the burden of the dying fell on Lis. By now, much had intervened between the sisters, and she’d forgiven Portia for this lapse. Lis was even grateful that only she had been present in the last minutes; it was a time she would rather not have shared. Lis would always remember the curiously muscular touch of her mother’s hand on Lis’s palm as she finally slipped away. A triplet of squeezes, like a letter in Morse code.

Now Lis suddenly found herself gasping for breath and realized that, in the grip of memory, she’d been working with growing fervor, the pace increasingly desperate. She paused and leaned against the pile of bags, already three-high.

She closed her eyes for a moment and was startled by her sister’s voice.

“So.” Portia plunged the shovel into the pile of sand with a loud chunk. “I guess it’s time to ask. Why did you really ask me out?”

14

At her sister’s feet Lis counted seven bags, filled, waiting to be piled up on the levee. Portia filled two more and continued, “I didn’t have to be here for the estate, right? I could’ve handled it

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher