![Praying for Sleep]()

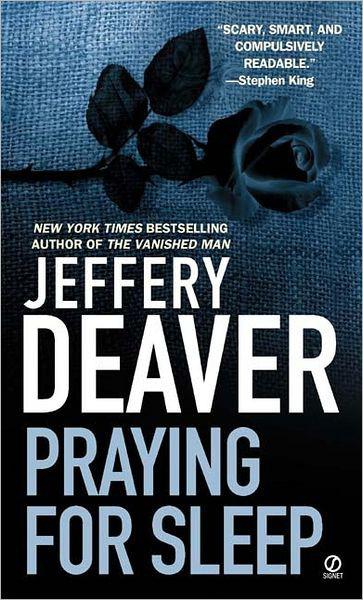

Praying for Sleep

coffee with milk. Kohler took his black. “Let’s go in here,” she said.

With their thin mugs of steaming coffee in hand they walked into the greenhouse, at the far end of which was an alcove. As they sat in the deep wrought-iron chairs, the doctor looked about the room and offered a compliment, which because it had to do only with square footage and neatness meant he knew nothing of, and cared little for, flowers. He sat with his legs together, body forward, making his thin form that much thinner. He took loud sips, and she knew he was a man accustomed to dining quickly and alone. Then he set the cup down and took a pad and gold pen from his jacket pocket.

Lis asked, “Then you have no idea where he’s going tonight?”

“No. He may not either, not consciously. That’s the thing about Michael—you can’t take him literally. To understand him you have to look behind what he says. That note he sent you, for instance; were certain letters capitalized?”

“Yes. That was one of the eeriest things about it.”

“Michael does that. He sees relationships between things that to us don’t exist. Could I see it?”

She found it in the kitchen and returned to the greenhouse. Kohler was standing, holding a small ceramic picture frame.

“Your father?”

“I’m told there’s a resemblance.”

“Some, yes. Eyes and chin. He was, I’d guess . . . a professor?”

“More of a closet scholar.” The picture had been taken two days after he’d returned from Jerez, and Andrew L’Auberget was shown here climbing into the front seat of the Cadillac for the drive back to the airport. Young Lis had clicked the shutter as she stood shaded by her mother’s protruding belly, inside of which her sister floated oblivious to the tearful farewell. “He was a businessman but he really wanted to teach. He talked about it many times. He would’ve made a brilliant scholar.”

“Are you a professor?”

“Teacher. Sophomore English. And you?” she asked. “I understand medicine runs in the genes.”

“Oh, it does. My father was a doctor.” Kohler laughed. “Of course he wanted me to be an art historian. That was his dream. Then he grudgingly consented to medical school. On condition that I study surgery.”

“But that wasn’t for you?”

“Nope. All I wanted was to be a psychiatrist. Fought him tooth and nail. He said if you become a shrink, it’ll chew you up, make you miserable, make you crazy and kill you.”

“So,” Lis said, “he was a psychiatrist.”

“That he was.”

“Did it kill him?”

“Nope. He retired to Florida.”

“About which, I won’t comment,” she said. He smiled. Lis added, “Why?”

“How’s that?”

“Why psychiatry?”

“I wanted to work with schizophrenics.”

“I’d think you’d make more money putting rich people on the couch. Why’d you specialize in that?”

He smiled again. “Actually, it was my mother’s illness. Say, is that the letter there?”

He took it in his short, feminine fingers and read it quickly. She could detect no reaction. “Look at this: ‘. . . they are holding me and have told lIes About Me to waShingtOn and the enTIRE worlD.’ See what he’s really saying?”

“No, I’m afraid I don’t.”

“Look at the capitalized letters. ‘I AM SO TIRED.’ ”

The encoded message sent a chill through her.

“There are a lot of layers of meaning in Michael’s world. ‘Revenge’ contains the name ‘Eve.’ ” He scanned the paper carefully. “ ‘Revenge,’ ‘eve,’ ‘betrayal.’ ”

He shook his head then set the letter aside and turned his hard eyes on her. She suddenly grew ill at ease. And when he said, “Tell me about Indian Leap,” a full minute passed before she began to speak.

Heading northeast from Ridgeton, Route 116 winds slowly through the best and the worst parts of the state: picturesque dairy and horse farms, then small but splendid patches of hardwood forests, then finally a cluster of tired mid-size towns studded with abandoned factories that the banks and receivers can’t give away. Just past one of these failed cities, Pickford, is a five-hundred-acre sprawl of rock bluffs and pine forest.

Indian Leap State Park is bisected by a lazy S-shaped canyon, which extends for half a mile from the parking lot off 116 to Rocky Point Beach, a deceptive name for what’s nothing more than a bleak rock revetment on a gray, man-made lake about one mile by two in size. Rising from the forest not far

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher