![Ptolemy's Gate]()

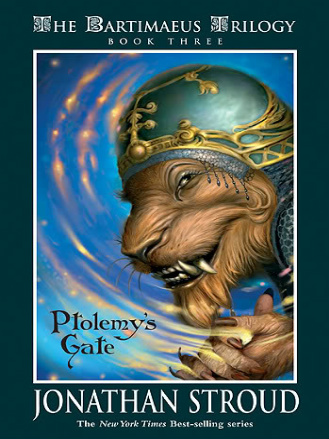

Ptolemy's Gate

Faquarl? Nouda? Did he deck his name out in neon lights and parade it round the town? I ask you! And I never told anyone!

You let it slip last time I summoned you.

Well, apart from that.

But you could have told his enemies, couldn't you, Bartimaeus? You'd have found a way to harm him if you'd really wished it. And Nathaniel knows that too, I think. I had a talk with him.

The boy looked thoughtful. Hmm. I know all about those talks of yours.

Anyway, he's gone for the Staff; I went to find you. Together —

The long and the short of it is that none of us are up to a fight. Not anymore. You won't be, for starters. As for Mandrake, last time he tried to use the Staff he knocked himself out. What makes you think he'll have the strength to do it now? He was exhausted last time I saw him. . . Meanwhile, my essence is so shot I couldn't maintain a simple form on Earth, let alone be useful. I probably couldn't even withstand the pain of materializing in the first place. Faquarl's got one thing right. He doesn't have to worry about the pain. No, let's face facts, Kitty — A pause. What? What's the matter?

The mannequin had tilted its bulbous head and was regarding the boy with an air of quiet intentness. The boy became uneasy.

What? What are you — ? Oh. No. Absolutely no way.

But, Bartimaeus, it would protect your essence. You wouldn't feel any pain.

Uh-uh. No.

And if you combined your power with his, maybe the Staff—

No.

What would Ptolemy have done?

The boy turned away. He crossed to the nearest pillar and sat down on the steps, looking out over the swirling void.

Ptolemy showed me the way it might have been, he remarked at last. He thought he would be the first of many — but in two thousand years you, Kitty, are the only one who's followed him. The only one. He and I conversed as equals for two years. I helped him out from time to time; in return he let me explore your world a little. I wandered as far as the Fezzan oasis and the pillared halls of Axum. I floated over the white crests of the Zagros Mountains and the dry stone gulches of the Hejaz deserts. I flew with the hawks and the cirrus clouds, high, high over earth and sea, and took with me memories of those places when I returned home.

As he spoke, little flickering images danced beyond the pillars of the hall. Kitty could not make them out, but she had little doubt they showed fragments of the wonders he had seen. She sent her mannequin to sit beside him on the step; their legs dangled out over nothingness.

The experience, the boy continued, was exhilarating. My freedom echoed that of my home, while my interest was roused by what I saw. The pain I felt was never too pressing, since I was able to return here when I wished. How I danced between the worlds! It was a great gift that Ptolemy gave me, and I have never forgotten it. I knew him for two years. And then he died.

How? Kitty asked. How did he die?

At first no answer came. Then:

Ptolemy had a cousin, the heir to the throne of Egypt. He feared my master's power. Several times he attempted to get rid of him, but we — the other djinn and I — stood in his way. Out among the swirling matter Kitty glimpsed recurring images of more than usual clarity: figures crouching on a window ledge, holding long curved swords; demons flitting over nighttime roofs; soldiers at a door. I would have taken him from Alexandria, particularly after his journey here had rendered him more vulnerable. But he was stubborn; he refused to go, even when Roman magicians arrived in the city and were housed by his cousin in the palace citadel. Brief flashes in the void: sharp triangular sails, ships below a lighthouse tower; six pale men in coarse brown cloaks standing on a quay.

It pleased my master, the boy went on, to be carried about the city most mornings, to let the scents of the markets drift over him — the spices, flowers, resins, hides, and skins. All the world was present in Alexandria, and he knew it. Besides, the people loved him. My fellow djinn and I carried him in his palanquin. Here Kitty caught the suggestion of a curtained chair, suspended on poles. Dark slaves supported it. Behind were stalls and people, bright things, blue sky.

The images winked out; the boy sat silent on the step.

One day, he continued, we took him to the spice market — his favorite place, where the scents were most intoxicating. We were foolish to do so; the streets were narrow, clogged with people. Progress was slow.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher