![Ptolemy's Gate]()

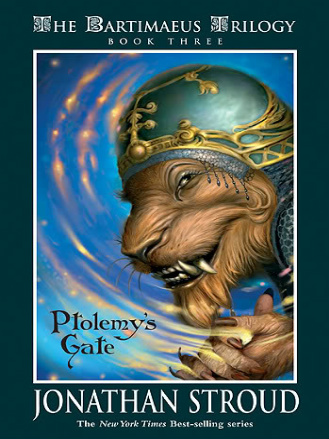

Ptolemy's Gate

into precocious dissipation. By his late teens he was a grotesque, loose-lipped youth, already potbellied with drink; his eyes glittered with paranoia and the fear of assassination. Impatient for power, he dawdled in the shadow of his father, seeking rivals in his blood-kin while waiting for the old man to die.

Ptolemy, by contrast, was a scholarly boy, slim and handsome, with features more nearly Egyptian than Greek.[5] Although distantly in line for the throne, he was clearly not a warrior or a statesman and was generally ignored by the royal household. He spent most of his time in the Library of Alexandria, close to the waterfront, studying with his tutor. This man, an elderly priest from Luxor, was learned in many languages and in the history of the kingdom. He was also a magician. Finding an exceptional student, he imparted his knowledge to the child. It was quietly begun and quietly completed, and only much later, with the incident of the bull, did rumor of it seep out into the wider world.

[5] They came from his mother's side, I guess. She was a native girl from upriver somewhere, a concubine in the royal apartments. I never saw her. She and his father died of plague before my time.

Two days afterward, while we were in discussion, a servant knocked upon my master's door. "Pardon me, Highness, but a woman waits without."

"Without what?" I wore the guise of a scholar, in case of just such an interruption.

Ptolemy silenced me with a gesture. "What does she want?" "A plague of locusts threatens her husband's crops, sir. She seeks your aid."

My master frowned. "Ridiculous! What can I do?" "Sir, she speaks of. . ." The servant hesitated; he had been with us in the field. "Of your power over the bull."

"This is too much! I am hard at work here. I cannot be disturbed. Send her away."

"As you wish." The servant sighed, made to close the door. My master stirred. "Is she very miserable?" "Mightily, sir. She has been here since dawn." Ptolemy gave a gasp of impatience. "Oh, this is rank foolishness!" He turned to me. "Rekhyt—go with him. See what can be done."

In due course I returned, looking plump. "Locusts gone." "Very well." He scowled at his tablets. "I have altogether lost the thread. We were talking about the fluidity of the Other Place, I believe. . ."

"You realize," I said, as I sat delicately on the straw matting, "that you've done it now. Got yourself a reputation. Someone who can solve the common ills. Now you'll never get any peace. Same thing happened to Solomon with the wisdom thing. Couldn't step outdoors without someone thrusting a baby in his face. Mind you, that was often for a different reason."

The boy shook his head. "I am a scholar, a researcher, nothing else. I shall aid mankind by the fruits of my writing, not by my success with bulls or locusts. Besides, it's you who's doing the work, Rekhyt. Do you mind removing that wing-case from the corner of your mouth? Thank you. Now, to begin . . ."

He was wise about some things, Ptolemy was, but not about others. The next day saw two more women standing outside his chambers; one had problems with hippos on her land, the other carried a sick child. Once again I was sent to deal with them as best I could. On the morning after that, a little line of people stretched out into the street. My master tore his hair and lamented his ill fortune; nevertheless I 'was dispatched again, along with Affa and Penrenutet, two of his other djinn. So it went. Progress on his research slowed to a snail's pace, while his reputation among the ordinary people of Alexandria grew fast as summer's flowering. Ptolemy suffered the interruptions with good, if exasperated, grace. He contented himself with completing a book on the mechanics of summoning and put his other inquiries aside.

The year aged, and in due time came the Nile's annual inundation. The floods went down, the dark earth shone fertile and wet, crops were planted, a new season began. Sometimes the queue of supplicants at Ptolemy's door was lengthy, at other times less so, but it never went away entirely. And it was not long before this daily ritual became known to the black-robed priests of the greater temples, and to the blackhearted prince sitting brooding on his wine-soused throne.

5

A disrespectful sound alerted Mandrake to the return of the scrying-glass imp. He put aside the pen with which he was scribbling notes for the latest war pamphlets, and stared into the polished disc. The baby's

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher