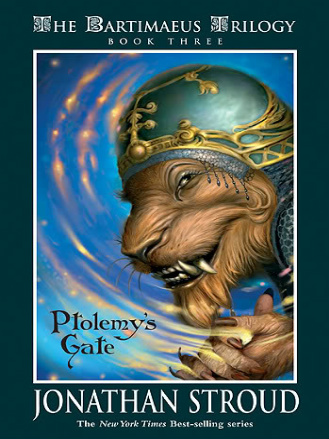

![Ptolemy's Gate]()

Ptolemy's Gate

water and the whiteness of the children's clothes enraged it. Head down, it charged upon the nearest girl, and would have gored or trampled her to death had not Ptolemy and I been strolling down that way.

The prince raised a hand. I acted. The bull stopped, mid-charge, as if it had collided with a wall. Head reeling, eyes crossed, it capsized into the dust, where it remained until attendants secured it with ropes and led it back into its field.

Ptolemy waited while his aides calmed the children, then resumed his constitutional. He did not refer to the incident again. Even so, by the time we returned to the palace a flock of rumors had taken flight and was swooping and swirling about his head. By nightfall everyone in the city, from the lowest beggar to the snootiest priest of Ra, had heard or misheard something of it.

As was my wont, I had wandered late among the evening markets, listening to the rhythms of the city, to the ebb and flow of information carried on its human tide. My master was sitting cross-legged on the roof of his quarters, intermittently scratching at his papyrus strip and gazing out toward the darkened sea. I landed on the ledge in lapwing's form and fixed him with a beady eye.

"It's all over the bazaars ," I said. "You and the bull." He dipped his stylus into the ink. "What matter?" "Perhaps no matter; perhaps much. But the people whisper."

"What do they whisper?"

"That you are a sorcerer who consorts with demons." He laughed and completed a neat numeral. "Factually, they are correct."

The lapwing drummed its claws upon the stone. "I protest! The term 'demon' is fallacious and abusive in the extreme!"[1]

[1] Note my restraint here. My standard of conversation was pretty high in those days, on account of conversing with Ptolemy. Something about him made you disinclined to be too vulgar, blasphemous, or impudent, and even made me rein in my use of estuary Egyptian slang. It wasn't that he forbade any of it, more that you ended up feeling a bit guilty, as if you'd let yourself down. Harsh invective was a no-no, too. It's surprising I had anything left to say.

Ptolemy put down his stylus. "It is a mistake to be too concerned with names and titles, my dear Rekhyt. Such things are never more than rough approximations, matters of convenience. The people speak thus out of ignorance. It's when they understand your nature and are still abusive that you will have to worry." He grinned at me sidelong. "Which is always possible, let's face it."

I raised my wings a little, allowing the sea wind to ruffle through my feathers. "Generally you come off well in the accounts so far. But mark my words, they'll be saying you let the bull loose soon."

He sighed. "In all honesty, reputation—for good or ill— doesn't much bother me."

"It may not bother you" I said darkly, "but there are those in the palace for whom the issue is life and death."

"Only those who drown in the stew of politics," he said. "And I am nothing to them."

"May it be so," I said darkly. "May it be so. What are you writing now?"

"Your description of the elemental walls at the margins of the world. So take that scowl off your beak and tell me more of it."

Well, I let it go at that. Arguing with Ptolemy never did much good.

From the beginning he was a master of curious enthusiasms. The accumulation of wealth, wives, and bijou Nile-front properties—those time-honored preoccupations of most Egyptian magicians—did not enthrall him. Knowledge, of a kind, was what he was after, but it was not the sort that turns city walls to dust and tramples on the necks of the defeated foe. It had a more otherworldly cast.

In our first encounter he threw me with it.

I was a pillar of whirling sand, a fashionable getup in those days. My voice boomed like rock-falls echoing up a gully. "Name your desire, mortal."

"Djinni," he said, "answer me a question."

The sand whirled faster."! know the secrets of the earth and the mysteries of the air; I know the key to the minds of women.[2] What do you wish? Speak."

[2] Patently all lies. Especially the last bit.

"What is essence?"

The sand halted in midair. "Eh?"

"Your substance. What exactly is it? How does it work?"

"Well, um . . ."

"And the Other Place. Tell me of it. Is time there synchronous with ours? What form do its denizens take? Have they a king or leader? Is it a dimension of solid substance, or a whirling inferno, or otherwise? What are the boundaries between your realm and this Earth,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher