![Ptolemy's Gate]()

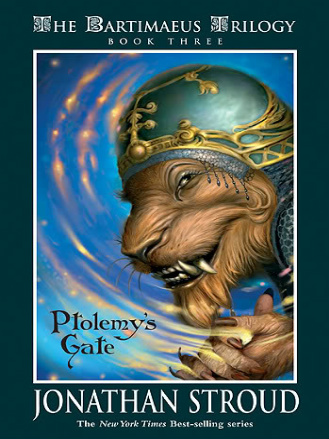

Ptolemy's Gate

and to what degree are they permeable?"

Um . . .

In short, Ptolemy was interested in us. Djinn. His slaves. Our inner nature, that is, not the usual surface guff. The most hideous shapes and provocations made him yawn, while my attempts to mock his youth and girlish looks merely elicited hearty chuckles. He would sit in the center of his pentacle, stylus on his knee, listening with rapt attention, ticking me off when I introduced a more than usually obvious fib, and frequently interrupting to clarify some ambiguity. He used no Stipples, no Lances, no other instruments of correction. His summonings rarely lasted more than a few hours. To a hardened djinni like me, who had a fairly accurate idea of the vicious ways of humans, it was all a bit disconcerting.

I was one of a number of djinn and lesser spirits regularly summoned. The normal routine never deviated: summons, chat, frenzied scribbling by the magician, dismissal.

In time, my curiosity was aroused. "Why do you do this?" I asked him curtly. "Why all these questions? All this writing?"

"I have read most of the manuscripts in the Great Library," the boy said. "They have much about summoning, chastisement, and other practicalities, but almost nothing about the nature of demons themselves. Your personality, your own desires. It seems to me that this is of the first importance. I intend to write the definitive work on the subject, a book that will be read and admired forever. To do this, I must ask many questions. Does my ambition surprise you?"

"Yes, in truth. Since when has any magician cared about our sufferings? There's no reason why you should. It's not in your interests."

"Oh, but it is. If we remain ignorant, and continue to enslave you rather than understand you, trouble will come from it sooner or later. That's my feeling."

"There is no alternative to this slavery. Each summons wraps us in chains."

"You are too pessimistic, djinni. Traders tell me of shamans far off among the northern wastes who leave their own bodies to converse with spirits in another world. To my mind, that is a much more courteous proceeding. Perhaps we too should learn this technique."

I laughed harshly. "It will never happen. That route is far too perilous for the corn-fed priests of Egypt. Save your energy, boy. Forget your futile questions. Dismiss me and have done."

Despite rny skepticism, he could not be dissuaded. A year went by; little by little my lies dried up. I began to tell him truth. In t urn, he told me something of himself.

He was the nephew of the king. At birth, twelve years before, he had been a frail and delicate runtling, coughing at the nipple, squealing like a kitten. His discomfort cast a pall over the ceremony of naming: the guests departed hurriedly, the silent officials exchanged somber looks. At midnight his wet nurse summoned a priest of Hathor,[3] who pronounced the infant close to death; nevertheless, he completed the necessary rituals and gave the child into the protection of the goddess. The night passed fitfully. Dawn came; the first rays of sun glimmered through the acacia trees and fell upon the infant's head. His squalling subsided, his body grew calm. Without noise or hesitation, he nuzzled at the breast and drank.

[3] Hathor: divine mother and protector of the newborn; djinn in her temples wore female guises with the heads of cattle.

The nature of this reprieve did not go unnoticed, and the child was swiftly dedicated to the sun god, Ra. He grew steadily in strength and years. Quick-eyed and intelligent, he was never as strapping as his cousin, the king's son,[4] eight years older and burly with it. Ptolemy remained a peripheral figure in the court, happier with the priests and women than with the sun-browned boys brawling in the yard.

[4] He was a Ptolemy, too. As they all were, these kings of Egypt, for 200 years and more, one after the other until Cleopatra spoiled the run. Originality was not the family's strong suit. Easy to see, perhaps, why my Ptolemy regarded names so casually. They meant little. He told me his the first time I asked him.

In those days the king was frequently on campaign, struggling to protect the frontiers against the incursions of the Bedouin. A series of advisers ruled the city, growing rich on bribes and port taxes, and listening ever closer to the soft words of foreign agents—particularly those of the emerging power across the water: Rome. Swathed in luxury in his marbled palace, the king's son fell

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher