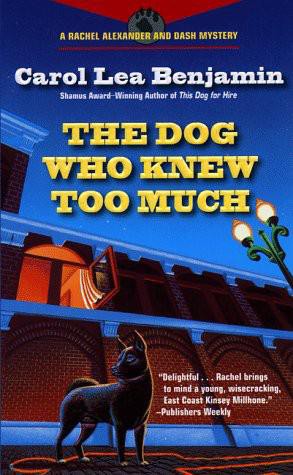

![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

Soft Scrub, and toilet brush. Everything was in order and covered with dust, to say the least.

Stewie didn’t have a desk in the small room. There was a Murphy bed, and it was closed, locked up against the wall. There was a small Formica table with wrought-iron legs and one chair near the pint-size kitchen appliances in what was called a Pullman kitchen, maybe because it could fit in one of those miniature rooms you could get on a train. Stewie’s breakfast coffee cup was in the sink, but the rest of the dishes were in the drainer. I’m sure if Beatrice were here she’d rewash them, but I had more urgent things to do.

It was after four, and Stewie could be home at any moment. I was hoping not to be here when he discovered his keys were missing, just in case the super had a set for emergencies such as this one.

I poked through Stewie’s closet, checking out his inexpensive and tasteless wardrobe, finding nothing but small change and used tissues in his linty pockets. I looked at the vegetables in his refrigerator, feeling that sour taste in my throat as I did. Perhaps I should have left the Fantastic out, to give him a hint, but there probably wasn’t any. Maybe it was made with animal products and he couldn’t use it, for political or moral reasons.

I looked through a pile of magazines on the floor near Stewie’s ratty couch, wondering why he wasn’t on the dole. Surely he lived as if he were hovering at the poverty line. But the magazines were expensive ones, all photography journals, and his books were mostly photography books. The expensive Nikon I’d seen at t’ai chi school was nowhere around. Maybe, like Diane Arbus , he liked to photograph life’s losers, so he took it to work with him. Maybe not. I wondered now if the wonderful photos I’d seen of Lisa had been his, or the one of Howie doing t’ai chi. No way those were drugstore prints. Anyone who did work like that had to have a darkroom, but dark as the apartment was, he wasn’t using the kitchen. There were no chemicals under the sink, no stores of paper, no enlarger in the small closet. And even if Stewie could have made do in the tiny bathroom, covering the window with thick black paper and laying a board over the tub to have a surface for the chemical baths and enlarger, still, the equipment just wasn’t there.

I went back to the books. Sure enough, several were about developing and printing black-and-white film. I looked around again to see if I had missed a place where Stewie could have stashed an enlarger, trays, and chemicals, but the place was small, and the storage practically nil.

I can’t recall who started sneezing first, me or Dashiell, but once I started, I kept going until there were tears coming out of my eyes.

I never heard the first few pops. I was probably still sneezing. By the time I realized what was happening, there were tissues everywhere. Like an idiot, I began to pick them up before separating Dashiell from the box, but no matter, he’d destroyed it already. One side had been mashed down by his big paw to anchor the box so that he could pull the tissues out. Now he was shaking the empty box violently from side to side, having the time of his life. I’d have no choice but to take the thing with me, ditch it in a garbage can on the street, and let Stewie figure he forgot he used his last Kleenex.

That’s when I heard it, the ping of something metallic and small hitting the dull parquet floor.

“Take it,” I told him, not seeing what it was, a coin perhaps. Or the rabies tag falling off his collar. I knew I had to find out what it was before leaving.

Dashiell’s mouth was right on the floor for a moment, which meant he was scooping something up with his tongue, something too small to get his teeth around. Then I heard it against his teeth as he chewed on it, trying to determine if luck were on his side and he’d picked up something edible, because don’t all dogs believe in their hearts that they aren’t fed nearly often enough?

I called him over, whispering in case someone were in the hall. It was a quarter to five now, time to get out of here.

I heard someone outside and froze in place. Dashiell was approaching me, and the sound of his nails click-clacking on the wooden floor seemed as loud as hailstones on the roof of a car. I signaled him to lie down by raising my arm over my head, then crept up to him and cupped my hand under his jaw.

“Out,” I whispered, hearing the footsteps in the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher