![Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set]()

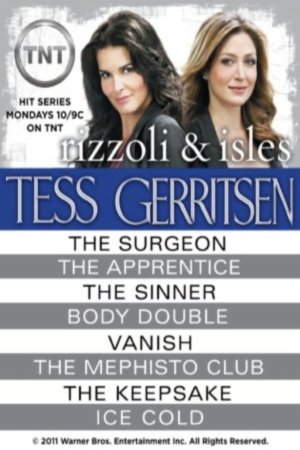

Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set

of the sacrificial goat’s final shudder, and I remember the pride in my mother’s eyes and the murmurs of approval from the circle of robed men. I want to feel that thrill again.

A fish will not do.

I remove the hook and drop the wriggling bass back into the lake. It gives a splash of its tail and darts away. The whisper of a breeze ruffles the water and dragonflies tremble on the reeds. I turn to Teddy.

And he says, “Why are you looking at me like that?”

TWENTY-FIVE

Forty-two Euros in tips—not a bad haul for a chilly Sunday in December. As Lily waved good-bye to the tour group whom she’d just shepherded through the Roman Forum, she felt an icy raindrop fleck her face. She looked up at dark clouds hanging ominously low and she shivered. Tomorrow she’d certainly need a raincoat.

With that fresh roll of cash in her pocket, she headed for the favorite shopping venue of every penny-pinching student in Rome: the Porta Portese flea market in Trastevere. It was already one P.M., and the dealers would be closing down their stalls, but she might have time to pick up a bargain. By the time she reached the market, a fine drizzle was falling. The Piazza di Porta Portese echoed with the clatter of crates being packed up. She wasted no time snatching up a used wool sweater for only three Euros. It reeked of cigarette smoke, but a good washing would remedy that. She paid another two Euros for a hooded slicker that was marred only by a single streak of black grease. Now dressed warmly in her new purchases, and with money still in her pocket, she indulged in the luxury of browsing.

She wandered down the narrow passage between stalls, pausing to pick through buckets of costume jewelry and fake Roman coins, and continued toward Piazza Ippolito Nievo and the antiques stalls. Every Sunday, it seemed, she always ended up in this section of the market, because it was the old things, the ancient things, that truly interested her. A scrap of medieval tapestry or a mere chip of bronze could make her heart pound faster. By the time she reached the antiques area, most of the dealers were already carting away their merchandise, and she saw only a few stands still open, their wares exposed to the drizzle. She wandered past the meager offerings, past weary, glum-faced sellers, and was about to leave the piazza when her gaze fell on a small wooden box. She halted, staring.

Three reverse crosses were carved into the top.

Her mist-dampened face suddenly felt encased in ice. Then she noticed that the hinge was facing toward her, and with a sheepish laugh, she rotated the box to its proper orientation. The crosses turned right-side up. When you looked too hard for evil, you saw it everywhere.

Even when it’s not there.

“You are looking for religious items?” the dealer asked in Italian.

She glanced up to see the man’s wrinkled face, his eyes almost lost in folds of skin. “I’m just browsing, thank you.”

“Here. There’s more.” He slid a box in front of her, and she saw tangled rosary beads and a wooden carving of the Madonna and old books, their pages curling in the dampness. “Look, look! Take your time.”

At first glance, she saw nothing in that box that interested her. Then she focused on the spine of one of the books. The title was stamped on the leather in gold:

The Book of Enoch.

She picked it up and opened it to the copyright page. It was the English translation by R. H. Charles, a 1912 edition printed by Oxford University Press. Two years ago, in a Paris museum, she had viewed a centuries-old scrap of the Ethiopic version.

The Book of Enoch

was an ancient text, part of the apocryphal literature.

“It is very old,” said the dealer.

“Yes,” she murmured, “it is.”

“It says 1912.”

And these words are even older

, she thought, as she ran her fingers across the yellowed pages. This text predated the birth of Christ by two hundred years. These were stories from an era before Noah and his ark, before Methusaleh. She flipped through the pages and paused at one passage that had been underlined in ink.

Evil spirits have proceeded from their bodies, because they are born from men, and from the holy Watchers is their beginning and primal origin; they shall be evil spirits on earth, and evil spirits shall they be called.

“I have many more of his things,” said the dealer.

She looked up. “Whose?”

“The man who owned that book. This is all his.” He waved at the boxes. “He died last

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher