![Saving Elijah]()

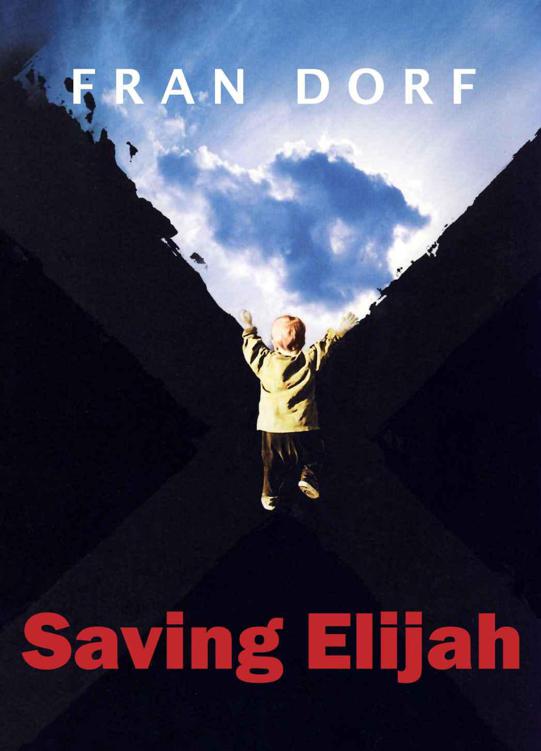

Saving Elijah

his chest, and pressed his nose to the glass. He stared into the tank for several minutes then pulled away, leaving little breath marks on the glass, tiny pearls, delicate as bubbles. He pursed and relaxed his lips, pursed and relaxed, pursed and relaxed, laughed at his own clowning, and moved on to the next tank. Finally, when he had finished looking into every single tank, he went back and pointed to the tanks where he'd seen a fish he particularly liked. This one. That one. And that one.

"But that's a tropical fish," the salesman said. "And it can only live in freshwater. And that one's a saltwater fish. And that one can only live in brackish water. You can't put them together."

Elijah put his glasses back on and stared up at the man. "Why?"

It was his favorite new word.

"Because you can't." The salesman looked at me.

"Because the freshwater fish doesn't like salt," I said.

Elijah shrugged. "He would if you gave him a chance."

"Look," the salesman said to me. "Why don't you just start out with a ten-gallon tank and a few small tropical fish? Just to get the hang of it. It's a little tricky to get the chemicals right in a saltwater tank."

"I like that one best." Elijah pointed to the large blue fish with the long nose, a saltwater variety.

We ended up with the saltwater tank, the blue fish with the long nose, and a yellow striped companion.

* * *

Sam's boss, Ed Larobina, had a friend with an epileptic daughter whose parents swore by her doctor, Dr. David Selson, of the Manhattan Medical Center.

"I called Selson's office and told them a little bit about Elijah," Sam said. "They said he'd be glad to give a second opinion. It's even covered by our insurance."

Elijah's hospitalization and follow-up had cost more than $250,000.

"Would we have to see Selson first?" We were scheduled for Moore's EEG the next day.

"No, but of course Selson's office could do the EEG, too. Or we can just take them the results."

"We might as well go ahead with Moore."

"Whatever you think." He came closer, put his hand on my shoulder. "Feel better?"

No.

"Where is everyone?"

"Alex and Kate are doing their homework. Elijah is fish watching."

"What's that?"

"You know how he's been bugging me to get him a fish. Well, we took the plunge, so to speak, this afternoon. We set the tank up in the dining room, and he's been in there ever since."

I followed Sam in. The lights were all off and the tank gave off an eerie blue glow.

"Well, now," Sam said, "those certainly are some beautiful fish." He switched on the light.

"Hi, Daddy." Elijah didn't turn around.

Sam leaned over and kissed his cheek. "Do they have names?"

Elijah shook his head and kept on staring into the tank.

"Look at that blue one," Sam said. "Wiggles his tail like he's dancing. You could always call him Elvis."

Elijah turned around and laughed. "Elvis," he said, and went back to fish watching.

"Dinner'll be ready in about twenty minutes," I said. "If Elijah can tear himself away."

I kissed him and he giggled.

* * *

The next morning Sam and I drove Elijah down to the hospital for his EEC I was nervous about it, unsure how he'd react to being tethered by his head to a machine for twenty-four hours.

Elijah walked between Sam and me, holding our hands as we took him up to the pedi-floor, where they gave us a room for the night. He didn't seem to mind the ordeal, even when they gooped up his head. He sat quietly while they hooked him up and even laughed when he saw himself in a mirror a little later.

We had brought along games and toys to keep him amused, but mostly he wanted to walk around and talk to the nurses and doctors, show off Tuddy and his Creatures of the Deep book. He had become so friendly and interested, not afraid of anything, even hallways full of white coats. The machine was portable, and we wheeled it around with us.

Just before they brought Elijah his dinner, Sam went home. Elijah ate everything on his plate except the hot dog, then we—Elijah (and Tuddy and the book), me, and the electroencephalographic machine—went into the little playroom. A girl of about eight was already in the room, playing listlessly with a Barbie doll. Her bloated little face was as pale as dough and she was nearly bald, with just a few wispy clumps of fluff on her head, like duck fuzz. I nodded at the mother hovering over her, a woman nearly as pale as her daughter, with deep raccoon-like circles under her eyes.

"This is Margaret," the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher