![Scratch the Surface]()

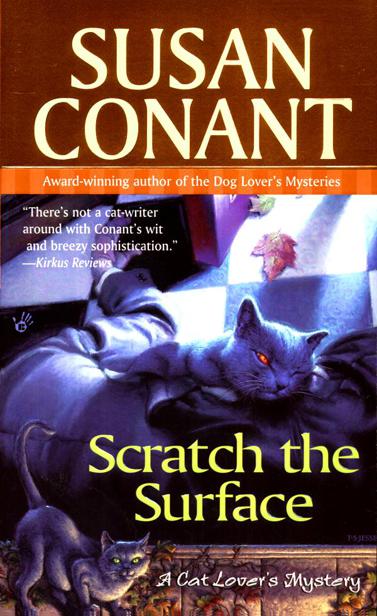

Scratch the Surface

application had been examined. In particular, no one had raised the question of whether she was, in fact, a widow, and no one had asked whether her financial circumstances were, in fact, severely reduced.

When Felicity parked Aunt Thelma’s unpretentious Honda CR-V in front of her mother’s building that afternoon, she uttered a short prayer: “Dear God, thank you for allowing the illegitimate nature of my mother’s occupancy to remain undetected. Gratefully yours, Felicity Pride.”

If a thorough and conscientious administrator ever examined the details of residents’ applications, would Mary be booted out? Sent a hefty rent bill for past years? Perhaps even charged with fraud? Probably not. Although Uncle Bob had been a man of influence, there was no reason to suppose that his sister was the only resident who’d slipped in under false pretenses. For all Felicity knew, not a single occupant of the attractive units was actually entitled to subsidized housing; the entire place was probably populated by the relatives of persons of financial or political power. And the units were attractive. The entrance hall of her mother’s building was spotless. A low table held a mixed bouquet of flowers in a glass vase. Tacked to a cork bulletin board above the table were notices of events: Children from a local school would give a concert on Thursday afternoon, a shuttle bus would transport people to a Boston theater on Saturday for the matinee performance of a musical comedy, and lessons in watercolor painting would begin on Monday at ten A.M.

Felicity rapped her knuckles on the first door on the left. “Mother?” She could hear the television. After a long wait, she rapped again and called loudly, “Mother! It’s Felicity!” Eventually, there was a sound of shuffling, and Mary said, “Who is it?”

“Felicity!”

“Who?”

“Felicity!”

The door opened. Mary wore a cotton duster, a flower-patterned garment halfway between a bathrobe and a dress. She made as if to hug and kiss Felicity, but succeeded only in scratching Felicity’s face with the brush rollers that covered her head. “Come in! Don’t stand out there. You’re letting in a draft. Those shoes are new. I always think that a woman with big feet should look for something with a short vamp.”

“They’re boots,” Felicity said. “It’s cold out.”

Mary settled herself in a padded lounger that faced the television. “I wouldn’t know,” Mary said. “I can’t get out very much.”

Won’t, thought Felicity as she turned off the TV.

“Sit down and tell me all about your murder,” her mother said. “It puts me in mind of my grandmother. She loved a murder. She spoke broad Scots, you know, and when the paper came, she always opened it and said, ‘Any guid meerders today?’ ”

“This wasn’t a particularly good murder. It wasn’t exactly pleasant to find—”

“Do you remember that woman who shot her husband and threw him over the bridge? You and Angie and I followed that in the papers. It went on for weeks. She and her boyfriend killed the husband. What was her name? Nancy? And the boyfriend was ten years younger than she was. She shot her husband in the head, but he didn’t die right away, so she called the boyfriend to finish him off and help her get rid of the body.”

“Could I have a cup of coffee?“ Felicity asked. “Do you want one?”

“Help yourself. Nothing for me. I had a nice poached egg for lunch. You know, Felicity, there’s something I’ve been meaning to ask you. This review you sent me? Of your book?”

“Yes?”

“There’s something I don’t understand.”

“Yes?”

“It says here you’re funny.”

“What do reviewers know?” Felicity moved to the small kitchen, which was separated from the living room by a divider. She put the kettle on and got out instant coffee, sugar, milk, and a cup and saucer. Her mother disapproved of mugs. As she fixed coffee for herself, her mother reminisced about other murders that the family had enjoyed following in the papers throughout Felicity’s childhood: husbands who had hired thugs to brain wayward wives with baseball bats, doctors and nurses who had habitually done in patients, mothers who had drowned their children in bathtubs.

Returning to the living room and taking a seat, Felicity said, “I’ve wondered whether the body was left at my house by mistake. It’s occurred to me that maybe someone didn’t know about Bob and Thelma and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher