![Scratch the Surface]()

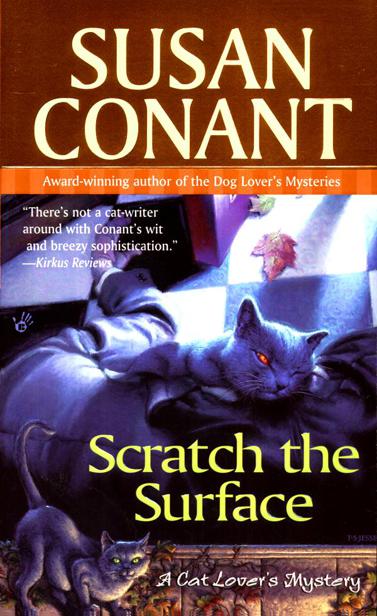

Scratch the Surface

had been possible for Felicity to open a window and eavesdrop, she might have done so. She was, however, fearful of getting caught. The Norwood Hill view of the residents of Newton Park was bad enough, and now Trotsky was making it worse! What was he doing home, anyway? Felicity grabbed a coat from her front hall closet. In her haste, she considered going out through the vestibule, but retained a superstitious desire to avoid it. If the snob with the dog assumed that anyone emerging from the back door must be a servant, too bad.

Striding down the paved path from the back door to the road, Felicity heard Mr. Trotsky yell, “And they are killing my grass, these dogs! Look at that! Dead! And do you know how much I pay for this lawn?”

“What’s killing your grass,” the woman said calmly, “isn’t dog urine. It’s drought. If you’d water the grass here by the street, it would be fine.” Her pronunciation of the word water irked Felicity, who never disgraced herself by saying “wat-uh,” but who could never get that first vowel quite right. This condescending Norwood Hill dog walker pronounced the miserable syllable with the effortless perfection of someone who hadn’t merely overcome her Boston accent, but had never had one to begin with. She probably didn’t have to think twice before uttering cork or caulk.

“This neighborhood is private property,” Mr. Trotsky informed her. He swept an arm around. “All private property.”

“If I’m trespassing,” countered the woman, “perhaps you should call the police. The Boston police will undoubtedly come running when they hear that my dog put her paw on your lawn.”

“Pardon me,” Felicity said, “but—”

Mr. Trotsky ignored her. “No dogs! No pets! No trespassers!”

“You know something?” asked the woman. “People who don’t know how to live in good neighborhoods shouldn’t move to them. Or anywhere near them. Until these houses went up, Norwood Hill was the quietest, safest place you can imagine, and now we have cars speeding down our narrow streets and ruining everything. As a matter of fact, a complaint has been lodged with your condominium association.” Before her Russian neighbor could respond, Felicity said, “I’m so sorry there’s trouble here. There’s no reason at all to object to having people walk through here. Most of us—”

“No pets!” shouted Mr. Trotsky. “A cat! I saw a cat in your window!” He turned his back on her and stomped to his house.

“Charming neighbor you have,” said the woman.

“He really is the exception,” said Felicity.

“I’d hope so. At least you’re not all Russian. There’s that to be thankful for. How they get their money out of Russia is a mystery to me. And how they made it to begin with!”

“This neighborhood is actually quite diverse,” Felicity said. “And I suspect that back in Russia, people found him pretty rude, too. If your dog wants to walk on a lawn, let him walk on mine. It won’t bother me.”

“Her. Her. She’s female!” With that, the woman clucked to the dog and walked briskly away.

Felicity went back inside and resumed her examination of her correspondence. It seemed to her that some of the reviews she’d received would have provided grounds for justifiable homicide, but the blurbs she’d written for the covers of other people’s mysteries, feline and otherwise, had been laudatory. She had, of course, declined to blurb some books, and she’d begged off reading some manuscripts, but it seemed to her that her refusals had been kind and tactful. For instance, to Janice Mattingly, she’d written, “How sorry I am not to have the treat of reading your manuscript right now! As it is, I am up against a looming deadline and barely have time to read my own book. I look forward to enjoying Tailspin when it comes out and certainly wish you the very best of luck with it.” She’d previously weaseled out of recommending Janice to her agent, too, but to the best of her recollection, she’d been equally inoffensive on that occasion.

As she was turning to old e-mail in search of slights and grudges, the phone interrupted her.

“So,” said her sister, “you find a corpse at your door, and you don’t even bother to tell me?” Angie’s Boston accent was intact: corpse was “cawpse,” door was “dough-uh.”

“I’m sorry. I told Mother.” Felicity had long ago discarded Ma. “I assumed she’d tell you. But I should’ve called. It’s

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher