![Secret Prey]()

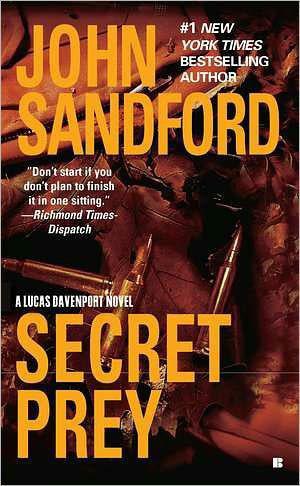

Secret Prey

victims asked that you be notified. An Officer Lucas Davenport.’’

‘‘Oh no! How bad is he?’’

‘‘He’s in surgery. I really don’t have any more information; a priest on the staff has been notified—we assumed he was Catholic.’’

‘‘Yes, he is. Is the priest doing extreme unction?’’

‘‘No, Officer Davenport is in surgery, but we thought a priest should be notified; it’s purely routine in these cases . . .’’

‘‘I’ll be right there.’’

‘‘If you will check with the information desk at the front entrance, not the emergency entrance, you will be directed to the surgical waiting area.’’

And the nun dropped the phone on the hook.

AUDREY BRACED HERSELF AGAINST THE WALL. IF THE nun came out the main entrance, the entrance closest to the parking lot, and headed straight toward the lot, she’d pass Audrey at little more than an arm’s length. Audrey would have only a moment to determine if she was alone. If she wasn’t, Audrey would follow her to Midway Hospital and try there—the nun would have to walk some distance to the main entrance, and would probably be dropped off.

She was rehearsing it all in her mind when she heard the main door open. No voices, just the clank of the push bar on the door, and the door opening. Three seconds later, a woman in a black habit swept by, and down the walk. Audrey instinctively knew she was alone: she was moving too quickly, with too much focus, to be with another person. Audrey swung out from behind the junipers, her heart gone to stone in her chest, a step and a half behind the nun.

And she struck, like an axman taking a head.

The heavy rod hit the nun on the side of the head, glanced off, hit the nun’s shoulder; the woman sagged, her knees buckling, one hand going to the ground. She started to turn.

And Audrey struck her again, this time full on the head, and the nun pitched forward on her face . . . Audrey lifted the dowel rod, her teeth bared, her breathing heavy, and struck at the nun’s head again, but from a bad angle: the rod this time bounced off the side of the nun’s head and into her shoulder.

With building fury, with the memory of all these decades of slights and slurs against her, with the thought of all the people who’d held her back and down, with her father, her mother, with all the others, Audrey struck again and again, hitting the nun’s neck and back and shoulder . . .

And heard the clank of the door again, froze, looked wildly around—nowhere to run, not at this instant, this was the very worst moment for an interruption—and stepped back in the shadow of the junipers. The girl came around the corner no more than a second later, saw the nun, said, ‘‘Sister!’’ and bent over her.

And Audrey struck at her, hitting the girl on the back of the head. Like the nun, the girl pitched forward, onto her face. Audrey hit her again, and again, breathing hard now. Stopped, hovered over the two motionless women for an instant, jabbed at the nun’s leg with the end of the dowel rod, got no response, then scuttled away. Around the corner, onto the sidewalk, down the sidewalk to the car. Nobody on the sidewalk. Inside the car, dowel rod on the floor—a sudden touch of panic: she felt her pocket. Yes! The phone was there—and the car started and she eased away from the curb.

This was always the hardest part, staying cool after an attack. With her heart beating an impossible rhythm, Audrey drove slowly off the campus, to the Mississippi, left to the bridge and across to Minneapolis.

She stopped once, on a dark street, to throw the dowel rod down a sewer. She went on, dropped the cotton gloves one at a time out the window. She hadn’t seen any blood from either of the women, but it had been dark: she should burn these clothes, or get rid of them, anyway.

That would have to wait—she could wash them tonight, immediately—and throw them out tomorrow.

But now, there was more to do.

Twenty minutes later, headlights on, she pulled into her driveway, and into the darkened garage. She dropped the garage door, groped to the kitchen entrance, went inside and flipped on the light.

Upstairs, she took off her clothes, inspected them closely. Nothing she could see. Still, they’d go in the washing machine. She picked up the phone: no messages. Good.

She dialed, got Helen: ‘‘Hello?’’

‘‘Helen . . . I just . . . can’t sleep,’’ she said, her voice crumbling. ‘‘I hate to bother you,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher