![Speaker for the Dead]()

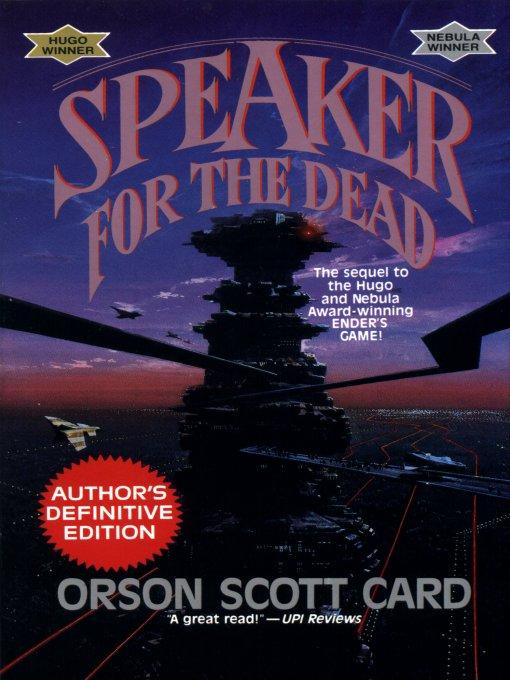

Speaker for the Dead

village to watch you and study you ."

Pipo answered as honestly as he could, but it was more important to be careful than to be honest. "If you learn so little and we learn so much, why is it that you speak both Stark and Portuguese while I'm still struggling with your language?"

"We're smarter." Then Rooter leaned back and spun around on his buttocks so his back was toward Pipo. "Go back behind your fence," he said.

Pipo stood at once. Not too far away, Libo was with three pequeninos, trying to learn how they wove dried merdona vines into thatch. He saw Pipo and in a moment was with his father, ready to go. Pipo led him off without a word; since the pequeninos were so fluent in human languages, they never discussed what they had learned until they were inside the gate.

It took a half hour to get home, and it was raining heavily when they passed through the gate and walked along the face of the hill to the Zenador's Station. Zenador? Pipo thought of the word as he looked at the small sign above the door. On it the word XENOLOGER was written in Stark. That is what I am, I suppose, thought Pipo, at least to the offworlders. But the Portuguese title Zenador was so much easier to say that on Lusitania hardly anyone said xenologer , even when speaking Stark. That is how languages change, thought Pipo. If it weren't for the ansible, providing instantaneous communication among the Hundred Worlds, we could not possibly maintain a common language. Interstellar travel is far too rare and slow. Stark would splinter into ten thousand dialects within a century. It might be interesting to have the computers run a projection of linguistic changes on Lusitania, if Stark were allowed to decay and absorb Portuguese--

"Father," said Libo.

Only then did Pipo notice that he had stopped ten meters away from the station. Tangents. The best parts of my intellectual life are tangential, in areas outside my expertise. I suppose because within my area of expertise the regulations they have placed upon me make it impossible to know or understand anything. The science of xenology insists on more mysteries than Mother Church.

His handprint was enough to unlock the door. Pipo knew how the evening would unfold even as he stepped inside to begin. It would take several hours of work at the terminals for them both to report what they had done during today's encounter. Pipo would then read over Libo's notes, and Libo would read Pipo's, and when they were satisfied, Pipo would write up a brief summary and then let the computers take it from there, filing the notes and also transmitting them instantly, by ansible, to the xenologers in the rest of the Hundred Worlds. More than a thousand scientists whose whole career is studying the one alien race we know, and except for what little the satellites can discover about this arboreal species, all the information my colleagues have is what Libo and I send them. This is definitely minimal intervention.

But when Pipo got inside the station, he saw at once that it would not be an evening of steady but relaxing work. Dona Cristã was there, dressed in her monastic robes. Was it one of the younger children, in trouble at school?

"No, no," said Dona Cristã . "All your children are doing very well, except this one, who I think is far too young to be out of school and working here, even as an apprentice. "

Libo said nothing. A wise decision, thought Pipo. Dona Cristã was a brilliant and engaging, perhaps even beautiful, young woman, but she was first and foremost a monk of the Order of the Filhos da Mente de Cristo, Children of the Mind of Christ, and she was not beautiful to behold when she was angry at ignorance and stupidity. It was amazing the number of quite intelligent people whose ignorance and stupidity had melted somewhat in the fire of her scorn. Silence, Libo, it's a policy that will do you good.

"I'm not here about any child of yours at all," said Dona Cristã. "I'm here about Novinha."

Dona Cristã did not have to mention a last name; everybody knew Novinha. The terrible Descolada had ended only eight years before. The plague had threatened to wipe out the colony before it had a fair chance to get started; the cure was discovered by Novinha's father and mother, Gusto and Cida, the two xenobiologists. It was a tragic irony that they found the cause of the disease and its treatment too late to save themselves. Theirs was the last Descolada funeral.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher