![Speaker for the Dead]()

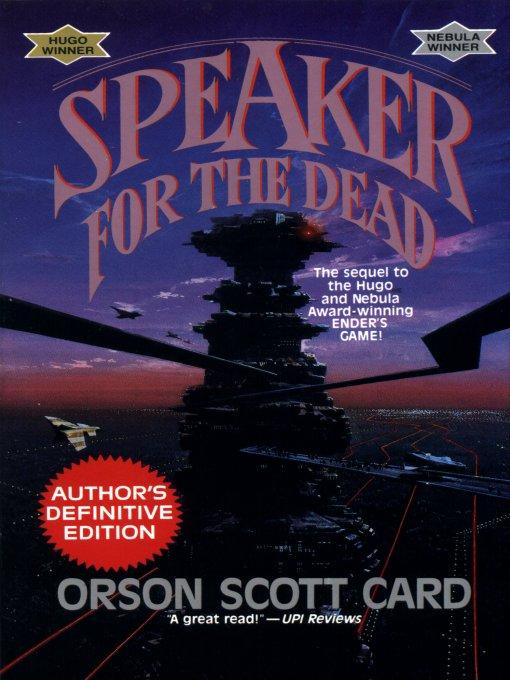

Speaker for the Dead

"Do you like her?" asked Pipo.

Libo paused for a moment in silence. Pipo knew what it meant. He was examining himself to find an answer. Not the answer that he thought would be most likely to bring him adult favor, and not the answer that would provoke their ire-- the two kinds of deception that most children his age delighted in. He was examining himself to discover the truth.

"I think," Libo said, "that I understood that she didn't want to be liked. As if she were a visitor who expected to go back home any day."

Dona Cristã nodded gravely. "Yes, that's exactly right, that's exactly the way she seems. But now, Libo, we must end our indiscretion by asking you to leave us while we--"

He was gone before she finished her sentence, with a quick nod of his head, a half-smile that said, Yes, I understand, and a deftness of movement that made his exit more eloquent proof of his discretion than if he had argued to stay. By this Pipo knew that Libo was annoyed at being asked to leave; he had a knack for making adults feel vaguely immature by comparison to him.

"Pipo," said the principal, "she has petitioned for an early examination as xenobiologist. To take her parents' place."

Pipo raised an eyebrow.

"She claims that she has been studying the field intensely since she was a little child. That she's ready to begin the work right now, without apprenticeship."

"She's thirteen, isn't she?"

"There are precedents. Many have taken such tests early. One even passed it younger than her. It was two thousand years ago, but it was allowed. Bishop Peregrino is against it, Of course, but Mayor Bosquinha, bless her practical heart, has pointed out that Lusitania needs a xenobiologist quite badly-- we need to be about the business of developing new strains of plant life so we can get some decent variety in our diet and much better harvests from Lusitanian soil. In her words, 'I don't care if it's an infant, we need a xenobiologist.'"

"And you want me to supervise her examination?"

"If you would be so kind."

"I'll be glad to."

"I told them you would."

"I confess I have an ulterior motive."

"Oh?"

"I should have done more for the girl. I'd like to see if it isn't too late to begin."

Dona Cristã laughed a bit. "Oh, Pipo, I'd be glad for you to try. But do believe me, my dear friend, touching her heart is like bathing in ice."

"I imagine. I imagine it feels like bathing in ice to the person touching her. But how does it feel to her? Cold as she is, it must surely burn like fire."

"Such a poet," said Dona Cristã . There was no irony in her voice; she meant it. "Do the piggies understand that we've sent our very best as our ambassador?"

"I try to tell them, but they're skeptical."

"I'll send her to you tomorrow. I warn you-- she'll expect to take the examinations cold, and she'll resist any attempt on your part to pre-examine her. "

Pipo smiled. "I'm far more worried about what will happen after she takes the test. If she fails, then she'll have very bad problems. And if she passes, then my problems will begin."

"Why?"

"Libo will be after me to let him examine early for Zenador. And if he did that , there'd be no reason for me not to go home, curl up, and die."

"Such a romantic fool you are, Pipo. If there's any man in Milagre who's capable of accepting his thirteen-year-old son as a colleague, it's you. "

After she left, Pipo and Libo worked together, as usual, recording the day's events with the pequeninos. Pipo compared Libo's work, his way of thinking, his insights, his attitudes, with those of the graduate students he had known in University before joining the Lusitania Colony. He might be small, and there might be a lot of theory and knowledge for him yet to learn, but he was already a true scientist in his method, and a humanist at heart. By the time the evening's work was done and they walked home together by the light of Lusitania's large and dazzling moon, Pipo had decided that Libo already deserved to be treated as a colleague, whether he took the examination or not. The tests couldn't measure the things that really counted, anyway.

And whether she liked it or not, Pipo intended to find out if Novinha had the unmeasurable qualities of a scientist; if she didn't, then he'd see to it she didn't take the test, regardless of how many facts she had memorized.

Pipo meant to be difficult. Novinha knew how adults acted

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher