![Strange Highways]()

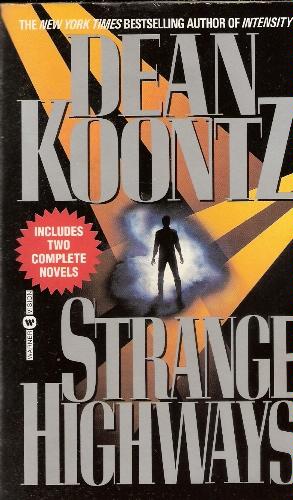

Strange Highways

naturally when he realized that God would never answer him. As the days passed without a miraculous sign assuring him that his mother's soul had survived death, Benny would begin to understand that all he had been taught about religion was true, and he eventually would return quietly to the realm of reason where I had made - and was patiently saving - a place for him. I did not want to tell him that I knew of his praying, did not want to force the issue, because I knew that in reaction to a too heavy-handed exercise of parental authority, he might cling even longer to his irrational dream of life everlasting.

But after four months, when his nightly conversations with his dead mother and with God did not cease, I could no longer tolerate even whispered prayers in my house, for though I seldom heard them, I knew they were being said, and knowing was somehow as maddening as hearing every word of them. I confronted him. I reasoned with him at great length on many occasions. I argued, pleaded. I tried the classic carrot-and-stick approach: I punished him for the expression of any religious sentiment; and I rewarded him for the slightest antireligious statement, even if he made it unthinkingly or if it was only my interpretation of what he'd said that made his statement antireligious. He received few rewards and much punishment.

I did not spank him or in any way physically abuse him. That much, at least, is to my credit. I did not attempt to beat God out of him the way my parents had tried to beat Him into me.

I took Benny to Dr. Gerton, a psychiatrist, when everything else had failed. "He's having difficulty accepting his mother's death," I told Gerton. "He's just not ... coping. I'm worried about him."

After three sessions with Benny over a period of two weeks, Dr. Gerton called to say he no longer needed to see Benny. "He's going to be all right, Mr. Fallon. You've no need to worry about him."

"But you're wrong," I insisted. "He needs analysis. He's still not ... coping."

"Mr. Fallon, you've said that before, but I've never been able to get a clear explanation of what behavior strikes you as evidence of his inability to cope. What's he doing that worries you so?"

"He's praying," I said. "He prays to God to keep his mother safe and happy. And he talks to his mother as if he's sure she hears him, talks to her every night."

"Oh, Mr. Fallon, if that's all that's been bothering you, I can assure you there's no need to worry. Talking to his mother, praying for her, all that's perfectly ordinary and-"

"Every night!" I repeated.

"Ten times a day would be all right. Really, there's nothing unhealthy about it. Talking to God about his mother and talking to his mother in Heaven ... it's just a psychological mechanism by which he can slowly adjust to the fact that she's no longer actually here on earth with him. It's perfectly ordinary."

I'm afraid I shouted: "It's not perfectly ordinary in this house, Dr. Gerton. We're atheists!"

He was silent, then sighed. "Mr. Fallon, you've got to remember that your son is more than your son - he's a person in his own right. A little person but a person nonetheless. You can't think of him as property or as an unformed mind to be molded-"

"I have the utmost respect for the individual, Dr. Gerton. Much more respect than do the hymn singers who value their fellow men less than they do their imaginary master in the sky."

His silence lasted longer than before. Finally he said, "All right. Then surely you realize there's no guarantee the son will be the same person in every respect as the father. He'll have ideas and desires of his own. And ideas about religion might be one area in which the disagreement between the two of you will widen over the years rather than narrow. This might not be only a psychological mechanism that he's using to adapt to his mother's death. It might also turn out to be the start of lifelong faith. At least you have to be prepared for the possibility."

"I won't have it," I said firmly.

His third silence was the longest of all. Then: "Mr. Fallon, I have no need to see Benny again. There's nothing I can do for him because there's nothing he really needs from me. But perhaps you should consider some counseling for yourself."

I hung up on him.

For the next six months Benny infuriated and frustrated me

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher