![Strange Highways]()

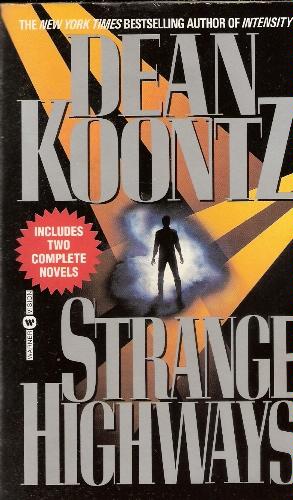

Strange Highways

by clinging to his fantasy of Heaven. Perhaps he no longer spoke to his mother every evening, and perhaps sometimes he even forgot to say his prayers, but his stubborn faith could not be shaken. When I spoke of atheism, when I made a scornful joke about God, whenever I tried to reason with him, he would only say, "No, Daddy, you're wrong," or, "No, Daddy, that's not the way it is," and he would either walk away from me or try to change the subject. Or he would do something even more infuriating: He would say, "No, Daddy, you're wrong," and then he would throw his small arms around me, hug me very tight, and tell me that he loved me, and at these moments there was a too apparent sadness about him that included an element of pity, as if he was afraid for me and felt that I needed guidance and reassurance. Nothing made me angrier than that. He was nine years old, not an ancient guru!

As punishment for his willful disregard of my wishes, I took away his television privileges for days - and sometimes weeks - at a time. I forbade him to have dessert after dinner, and once I refused to allow him to play with his friends for an entire month. Nothing worked.

Religion, the disease that had turned my parents into stern and solemn strangers, the disease that had made my childhood a nightmare, the very sickness that had stolen my best friend, Hal Sheen, from me when I least expected to lose him, religion had now wormed its way into my house again. It had contaminated my son, the only important person left in my life. No, it wasn't any particular religion that had a grip on Benny. He didn't have any formal theological education, so his concepts of God and Heaven were thoroughly nondenominational, vaguely Christian, yes, but only vaguely. It was religion without structure, without dogma or doctrine, religion based entirely on childish sentiment; therefore, some might say that it was not really religion at all, and that I should not have worried about it. But I knew that Dr. Gerton's observation was true: This childish faith might be the seed from which a true religious conviction would grow in later years. The virus of religion was loose in my house, rampant, and I was dismayed, distraught, and perhaps even somewhat deranged by my failure to find a cure for it.

To me, this was the essence of horror. It wasn't the acute horror of a bomb blast or plane crash, mercifully brief, but a chronic horror that went on day after day, week after week.

I was sure that the worst of all possible troubles had befallen me and that I was in the darkest time of my life.

Then Benny got bone cancer.

Nearly two years after his mother died, on a blustery day late in February, we were in the park by the river, flying a kite. When Benny ran with the control stick, paying out string, he fell down. Not just once. Not twice. Repeatedly. When I asked what was wrong, he said that he had a sore muscle in his right leg: "Must've twisted it when the guys and I were climbing trees yesterday."

He favored the leg for a few days, and when I suggested that he ought to see a doctor, he said that he was feeling better.

A week later he was in the hospital, undergoing tests, and in another two days, the diagnosis was confirmed: bone cancer. It was too widespread for surgery. His physicians instituted an immediate program of radium treatments and chemotherapy.

Benny lost his hair, lost weight. He grew so pale that each morning I was afraid to look at him because I had the crazy idea that if he got any paler he would begin to turn transparent and, when he was finally as clear as glass, would shatter in front of my eyes.

After five weeks he took a sudden turn for the better and was, though not in remission, at least well enough to come home. The radiation and chemotherapy continued on an outpatient basis. I think now that he improved not due to the radiation or cytotoxic agents or drugs but simply because he wanted to see the cherry trees in bloom one last time. His temporary turn for the better was an act of sheer will, a triumph of mind over body.

Except for one day when a sprinkle of rain fell, he sat in a chair under the blossom-laden boughs, enjoying the spring greening of the valley and delighting in the antics of the squirrels that came out of the nearby woods to frolic on our lawn. He sat not in one of the redwood lawn chairs but in a big, comfortably padded

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher