![The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared]()

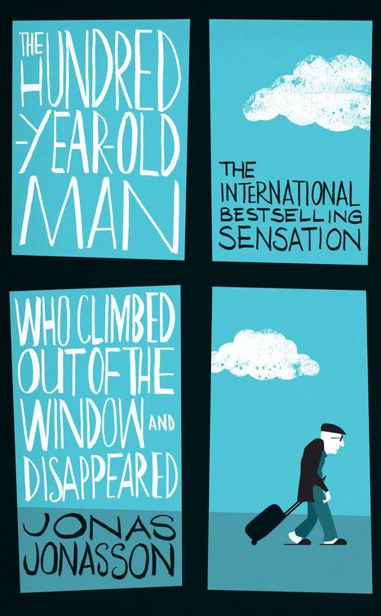

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared

ambulance men had wrapped a couple of hospital blankets round him, which wasn’t really necessary because the fire from the house that had almost burnt to the ground still gave off quite a lot of heat.

‘Mr Karlsson, I understand that you have blown up your house?’ said social worker Söder.

‘Yes,’ said Allan. ‘It’s a bad habit of mine.’

‘Let me guess that you, Mr Karlsson, are no longer in possession of an abode?’ the social worker continued.

‘There is some truth in that,’ said Allan. ‘Do you have any suggestions, Mr Social Worker?’

The social worker couldn’t think of anything on the spot, so Allan – at the expense of social services – was carted off to the hotel in the centre of Flen, where the following evening Allan, in a festive atmosphere, celebrated New Year with, among others, social worker Söder and his wife.

Allan hadn’t been in such fancy surroundings since the time just after the war when he had stayed at the luxurious Grand Hotel in Stockholm. In fact, it was high time he paid the bill there, because in the rush to leave it never got paid.

At the beginning of January 2005, social worker Söder had located a possible place of residence for the nice old man who had happened to become suddenly homeless a week earlier.

So Allan found himself at Malmköping’s Old People’s Home, where room 1 had just become available. He was welcomed by Director Alice, who smiled a friendly smile, but who also sucked the joy out of Allan’s life in laying out for him all the rules of the Home. Director Alice said that smoking was forbidden, drinking was forbidden, and TV was forbidden after eleven in the evening. Breakfast was served at 6.45 on weekdays and an hour later at weekends. Lunch was at 11.15, coffee at 15.15 and supper at 18.15. If you were out and didn’t keep track of the time and came home too late, you risked having to go without.

After which, Director Alice went through the rules concerning showers and brushing your teeth, visits from outside and visits to other resident senior citizens, what time various medicines were handed out and between which times you couldn’t disturb Director Alice or one of her colleagues unless it was urgent,which it rarely was according to Director Alice who added that in general there was too much grumbling among the residents.

‘Can you take a shit when you want to?’ Allan asked.

Which is how Allan and Director Alice came to be at odds less than fifteen minutes after they had met.

Allan wasn’t pleased with himself over the matter of the war against the fox back home (even though he won). Losing his temper was not in his nature. Besides, now he had used language that the director at the home might well have deserved, but which nevertheless was not Allan’s style. Add to that the mile-long list of rules and regulations that Allan now had to abide by…

Allan missed his cat. And he was ninety-nine years and eight months old. It was as if he had lost control of his own spirits, and Director Alice had had a lot to do with that.

Enough was enough.

Allan was done with life, because life seemed to be done with him, and he was and always had been a man who didn’t like to push himself forward.

So he decided that he would check into room 1, have his 18.15 supper and then – newly showered, in clean sheets and new pyjamas – he would go to bed, die in his sleep, be carried out, buried in the ground and forgotten.

Allan felt an almost electric sense of pleasure spreading through his body when, at eight o’clock in the evening, for the first and last time he slipped into the sheets of his bed at the Old People’s Home. In less than four months, his age would reach three figures. Allan Emmanuel Karlsson closed his eyes and felt perfectly convinced that he would now pass away for ever. It had been exciting, the entire journey, but nothing lasts for ever, except possibly general stupidity.

Then Allan didn’t think anything more. Tiredness overcame him. Everything went dark.

Until it got light again — a white glow. Imagine that, death was just like being asleep. Would he have time to think before it was all over? And would he have time to think that he had thought it? But wait, how much do you have to think before you have finished thinking?

‘It is a quarter to seven, Allan, time for breakfast. If you don’t eat it up, we shall take your porridge away and then you won’t have anything until lunch,’ said

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher