![The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared]()

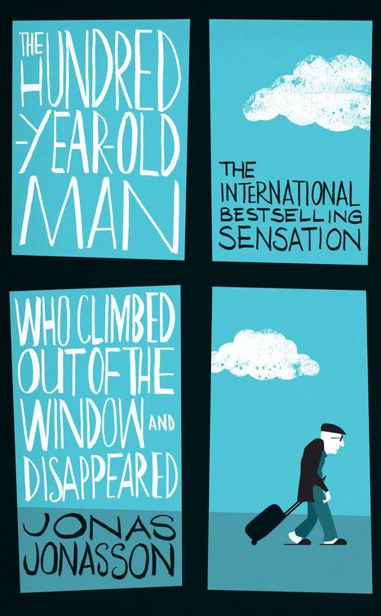

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared

boy, Ah Ming, was delighted by Jiang Qing’s promise that he would be able to serve Mao himself. The boy had secretly become a communist when he saw how the soldiers behaved, so he was fine with changing sides and advancing his career at the same time.

Allan, however, said that he was certain the communist struggle would manage just fine without him . So he assumed it would be okay if he went home. Did Jiang Qing agree?

Yes, she did. But ‘home’ was surely Sweden and that was terribly far away. How was Mr Karlsson going to manage?

Allan replied that boat or aeroplane would have been the most practical method but poor placement of the world’s oceans had ruled out catching a boat from the middle of China, and he hadn’t seen any airports up there in the mountains. And anyway he didn’t have any money to speak of.

‘So I’ll have to walk,’ said Allan.

The head of the village that had so generously received the three fugitives had a brother who had travelled more than anybody else. The brother had been as far afield as Ulan Bator in the north and Kabul in the west. Besides which, he had dipped his toes into the Bay of Bengal on a journey to the East Indies, but now he was home in the village again and the headman sent for him and asked him to draw a map of the world for Mr Karlsson so that he could find his way back to Sweden. The brother promised to do that and he had completed the task by the next day.

Even if you’re well bundled up, it is bold to cross the Himalayas with only the help of a homemade map of the world and a compass. In fact, Allan could have walked north of the mountain chain and the Aral and Caspian Seas, but reality and the homemade map didn’t exactly match up. So Allan said goodbye to Jiang Qing and Ah Ming and started upon his perambulation, which was to go through Tibet, over the Himalayas, through British India, Afghanistan, into Iran, on to Turkey and then up through Europe.

After two months on foot, Allan discovered that he must have chosen the wrong side of a mountain range and the best way to deal with that was to turn back and start over. Another four months later (on the right side of the mountain range) Allan realised he was making rather slow progress. At a market in a mountain village he haggled as best he could about the price of a camel, with the help of sign language and the Chinese he knew. Allan and the camel seller finally came to an agreement, but not until the seller had been forced to accept that Allan was not going to take in his daughter as part of the purchase.

Allan did consider the part about the daughter. Not for purely physical reasons, because he no longer had any such urges. They had been left behind in a bucket in ProfessorLundborg’s operating theatre. It was rather her companionship that attracted him. Life on the Tibetan highland plateau could sometimes be lonely.

But since the daughter spoke nothing but a monotonous-sounding Tibeto-Burmese dialect that Allan didn’t understand, he thought that where intellectual stimulation was concerned he could just as well talk to the camel. Besides, one couldn’t rule out that the daughter might have certain sexual expectations as to the arrangement. Something in the way she looked at him led Allan to believe that to be the case.

So another two months of loneliness ensued, with Allan wobbling across the roof of the world on the back of a camel, before he came across three strangers, also on camels. Allan greeted them in the languages he knew: Chinese, Spanish, English and Swedish. Luckily, English worked.

Allan told his new acquaintances that he was on his way home to Sweden. The men looked at him wide-eyed. Was he going to ride a camel all the way to northern Europe?

‘With a little break for the ship across Öresund,’ said Allan.

The three men didn’t know what Öresund was so Allan told them that it was where the Baltic Sea met the Atlantic Ocean. After they had ascertained that Allan was not a supporter of the British-American lackey, the Shah of Iran, they invited him to accompany them.

The men told him that they had met at university in Tehran where they had studied English. After their studies, they had spent two years in China, breathing the same air as their communist hero, Mao Tse-tung, and they were now on their way back home to Iran.

‘We are Marxists,’ one of the men said. ‘We are pursuing our struggle in the name of the international worker; in his name we will carry out a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher