![The Barker Street Regulars]()

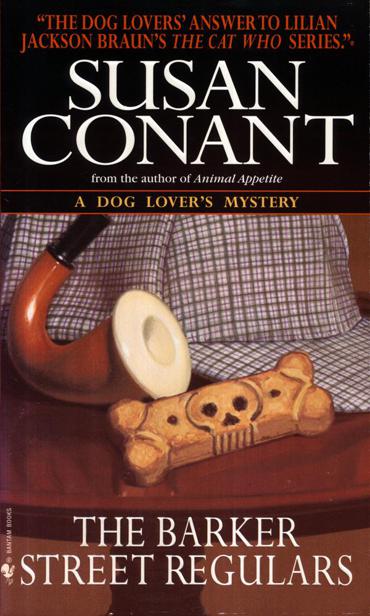

The Barker Street Regulars

dog euthanized before I can return the call. Alternately, the owner may give the dog away free to the kind of “good home” that beats him, sells him to a research laboratory, uses him in the so-called sport of dog fighting, or simply dooms him to years of neglect tied outside on a rope or cable.

This call, however, was from one of Steve’s vet techs, Rowena, who cheerfully informed me that my cat was ready to go home.

“It’s not my cat.” A call about any Alaskan malamute is a call about my dog.

“There must be some mix-up,” Rowena replied. “We have her here under your name.”

“It’s like Winnie the Pooh,” I said, “living under the name Sanders. Remember? Pooh had a sign over his door that said Sanders. Well, that cat is living under the name Winter.” Living under my name. Instead of dying underwater, “I’ll pick it up this afternoon,” I said grudgingly.

“If you don’t pick her up by noon,” Rowena said apologetically, “we’ll have to charge you for another day.”

Twenty minutes later I was standing at the tall counter in Steve’s waiting room as Rowena entered my name in the computer, found the cat’s file, and asked whether I’d come up with a name for her yet. Three or four people with cats in carriers or dogs on leash waited on the benches. I felt ashamed to have them hear me admit that I was the kind of heartless person who doesn’t name a pet.

“It’s not my cat,” I said. Suddenly inspired, I gave Rowena a big smile. “Maybe you’d like it.”

Shaking her dark curls, she returned the smile. “Sorry, but I’ve got three already. The doctor wants to talk to you before you leave. He’s with a patient now. Could you wait a couple of minutes?”

Instead of taking a seat, talking to the human and animal clients in the waiting room, or gritting my teeth at Steve’s mother’s embroidered and framed depictions of what are supposed to be terriers, I paced around, looked behind the counter, craned my neck, and scanned the notice board near the phone. Posted on it were business cards of dog trainers, contact information for humane societies and animal shelters, a list of obedience clubs, and notes and fliers about lost and found pets. Could I take the cat to an animal shelter? Every no-kill shelter I’d ever heard of avoided euthanasia by accepting young, healthy, adoptable animals while rejecting the old, the needy, and the difficult. The cat would never pass the screening. If I handed it over to one of the other facilities, it would probably be dead before I drove out of the parking lot. I was a person who rescued animals from shelters, at least from shelters where the staff really cared about the animals and called when a malamute came in. In contrast, a certain animal rescue league in Boston inexplicably refused to work with breed rescue groups. When the shelter manager told me that the policy was to euthanize dogs rather than to turn them over to rescue groups, I was insulted. I still am. Is a malamute better off dead than with me? And the organizations devoted to rescuing cats were so overwhelmed with stray and abandoned animals that I couldn’t bear to add another to the existing burden. No, I’d place the cat myself.

The lost-and-found notices suggested a wonderful new possibility. The despicable man in the dark van had yelled that the cat wasn’t even his. If he’d been telling the truth, maybe someone actually wanted the poor ugly thing back. Most of the lost animals whose descriptions and crudely photocopied snapshots were posted by the Phone were dogs: a beagle mix, a terrier mix who looked like Benji, a Great Pyrenees, a Doberman. Arabbit was missing. The only cat was a long-haired calico.

When Rhonda, another of Steve’s staff, ushered me into an empty exam room, she looked sad. “How do you think he’s doing?” she asked. She meant Steve.

“He’s holding up,” I said. “He’s making an effort. I wish he’d talk about it, but he won’t.”

“He got another letter from that woman today.”

“Gloria.”

Rhonda nodded.

“What did it say?”

“He tore it up. I didn’t see it.”

The swinging door opened, and Steve came in with the cat in his arms. When he’s about to discuss an animal, he always wears a serious expression. A stranger might not have noticed the tension in his jaw or the fine lines around his mouth. As he gently placed the cat on the metal exam table, he began to deliver one of his clear, maddeningly slow

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher