![The Barker Street Regulars]()

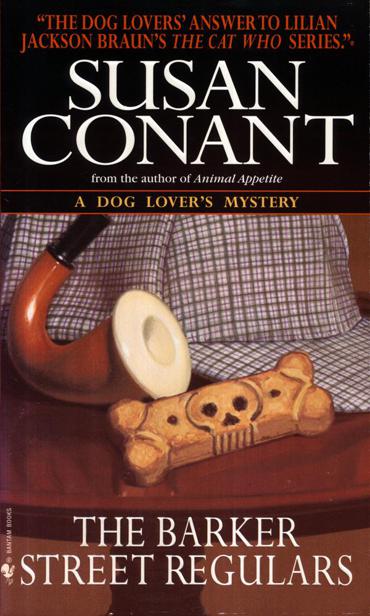

The Barker Street Regulars

I’d been warned to speak loudly. “I love him, too,” I bellowed awkwardly. “His name is Rowdy.”

On our second visit, with no prompting, Nancy called out Rowdy’s name and repeated it over and over: “Rowdy. Rowdy. I love him. I love him. Rowdy. Rowdy.” Licking her hands and face, Rowdy reminded me of a burly wolf tending to an emaciated feral child. Nancy suddenly looked away from Rowdy and directly at me. Her eyes were a faded hazel. She had more wrinkles than she did actual face. “God’s creature,” she said.

“Yes,” I agreed.

Entering the Gateway for our regular Friday morning visit, Rowdy and I always found a group of five or six sociable women in the lobby, their wheelchairs arranged in a welcoming half circle across from the elevators and next to the big dining hall. As soon as I’d signed in, pinned on my volunteer’s badge, and hung my parka in a closet rather alarmingly marked OXYGEN, I’d take Rowdy to the lobby, where the women made a fuss over him and helped me to train him to offer his paw gently and never to bat at people. The elderly, I’d been advised, have thin, fragile skin. On our first few visits, Rowdy himself proved more thin-skinned than I’d expected. He whined a few times and stayed so close to my left side that an obedience judge would have faulted him for crowding. Rowdy had been around wheelchairs before, but never so many as he encountered at the Gateway. And although he was used to the chaos of dog shows, the newness of everything at the nursing home taxed him.

Leaving the first floor, we took the elevator to the third. Near the nursing station, we always found a beautifully groomed woman who owned an enviable wardrobe of handsome business suits, silk blouses, and flower-patterned scarves. She never spoke a word to me. It took me a couple of visits to realize that although she didn’t want a big dog anywhere near her, she enjoyed looking at Rowdy from a distance of two or three yards. There was a tidy brown-skinned man named Gus whose wheelchair was always stationed in the TV room on the third floor. Gus liked to tell me about the German shepherd dogs he’d had. On every visit, he told me about his shepherds in the same words he’d used the last time I’d been there. Rowdy didn’t lick Gus’s face. Gus wouldn’t have liked it. “Shake!” Gus would demand. Rowdy would offer his paw, and he and Gus would exchange a dignified greeting. Then Gus would look back at the television screen, and Rowdy and I would move on, pausing in the hallways and stopping here and there in people’s rooms. In the corridors and elevators, the staff of the Gateway and people who lived there commented on Rowdy. Again and again, people reached out to touch him. There was an almost religious fervency about that need to lay a hand on him. I imagined the Gateway as a deviant yet orthodox temple and Rowdy as a canine Torah.

Big, vibrant, and boundlessly affectionate though Rowdy is, there was never enough of him to go round. To avoid overburdening Rowdy, I’d been ordered to limit my first visit to twenty-five minutes and to lengthen our stays gradually. In thirty minutes, we could have given one minute each to thirty people, five minutes each to six people, a rich fifteen minutes to two. No one got enough. No one except Althea Battlefield, who wasn’t even wild about dogs.

The plastic plaque on the wall outside Althea’s room on the fifth and top floor of the Gateway displayed two names: A. BATTLEFIELD and H. MUSGRAVE. Althea’s roommate, Helen, was a sprightly little woman who took frequent advantage of the numerous events listed in the Gateway’s monthly calendar and posted on the little kiosk in the first-floor lobby. I never found Helen napping on her bed. Rather, when she wasn’t having her hair done or attending a sing-along, a coffee hour, or an arts and crafts class, she bustled around rearranging the greeting cards, snapshots, and photocopied notices pinned to her cork bulletin board. I have never understood how Helen managed to keep track of the Gateway’s elaborate schedule of events. Her delight in the family photographs and cards on her bulletin board sprang in part from the perpetual novelty they held for her. The identities of the pleasant-looking people in the pictures were a mystery to her; she puzzled over the handwritten messages and signatures on the cards. The first time Rowdy and I entered Helen and Althea’s room, Helen, whose bed was the one

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher