![The Beginning of After]()

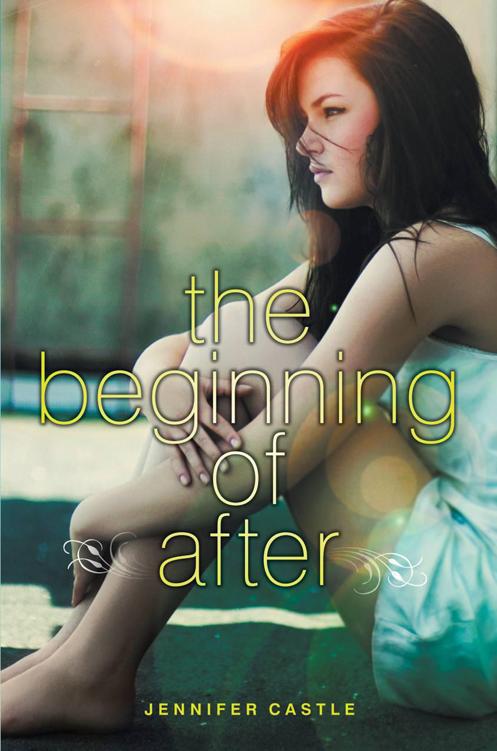

The Beginning of After

which wasn’t often. Sometimes I’d visit her studio and there would be an easel in the corner, tucked away like she was ashamed of it. A half-finished image of an old man on a park bench, or an abstract splatter of shapes that only suggested a face. Mom often talked about entering art shows or trying to arrange a gallery collection, but it never happened. The work that earned her a living took priority.

In our own house, there were just two of her paintings. One of my dad that she painted shortly after they first met, when he was still writing for a newspaper in the city. He’s sitting in front of an open window with skyscrapers and looks so young, most people who saw it thought it was Toby. I always used to look at that painting and think about him giving up the newspaper job for one in advertising right after they got married and Mom got pregnant, because it offered a higher salary.

They had each made their sacrifices, for our family.

The other painting, hanging in our dining room, was one of my brother and me as little kids, leaning against a tree in our backyard. We have the same face, an eerie medley of our mother’s and father’s features; I’m just taller and have longer straight brown hair than he does. I’m holding a cat that I don’t remember us ever owning.

“You have so much talent,” Mom had said to me the last time she saw one of my scenery flats. “But you never draw people.”

“I can’t. I’ve tried. They come out looking really disturbing.” We’d had this conversation at least a dozen times by then.

“Take a life drawing class. There’s a good one at the community arts center.”

“I just don’t have time,” I’d said to her, but to myself: She’s so embarrassed. It must suck to be a portrait painter and have a daughter who can only draw scenery!

She used to take me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art once a month. I loved those trips, even though she often borrowed my drawing pad to go sit on a bench somewhere, sketching other visitors, while I wandered the rooms alone.

The sadness came into my chest again, so I pushed away the image of my mother sketching and thought of how much I loved taking a tall canvas and turning it into something with dimension and depth; a street that curves on forever or deep rows of green hills. Maybe the truth was, I just didn’t like painting people.

“How are they doing with the flats?” I asked Meg.

“They still need some work. That’s why it would be great for you to come and help. Even Sam said so.”

“That’s just because of what’s happened. Do you remember how obnoxious he was a few weeks ago when I tried to start a house without him?” Samuel Ching was the stage manager in charge of the sets and generally a control freak. I was a better artist than he was, everyone knew it, but he never let me do anything without his approval. Once he painted over an Alp I did for The Sound of Music , which made me cry a little.

“I remember,” said Meg, “but they really do need you.”

I followed her into the auditorium, where most of the cast was goofing off in the seats and some of the finished scenery flats—a stone wall, a front door—were already onstage. She nodded me a little silent good-bye, and I headed for the backstage door. Inside, I found Samuel cleaning paintbrushes in front of a blank scenery flat.

“Hi, Sam,” I said.

He looked up at me and seemed surprised at first, but then his mouth settled into something practiced.

“Laurel, I’m so glad to see you!”

“Need help?” Now I felt we were reciting lines in a little play of our own.

“Do we ever. Here,” he said, handing me a brush and nodding toward the tall canvas. “This is the town square wall you sketched out before”— he tripped up for a moment—“last time. Do you think you could tackle it?”

Sam usually liked to be the one to paint on my sketches. It always felt like he was grabbing credit for the things I drew, but I couldn’t do anything about it because he was a senior and in charge and I didn’t want to be a whiny tattletale.

Now I smiled and said, “Just leave it to me.”

The next day, at my locker, taking too long to switch out my books because I knew I could be late for class and it wouldn’t matter, I overheard two seniors talking around the corner.

“I can’t believe Laurel Meisner’s back already,” said one, whose voice I couldn’t identify. I froze when I heard my name.

“Yeah, if it were me, I’d pull

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher