![The Beginning of After]()

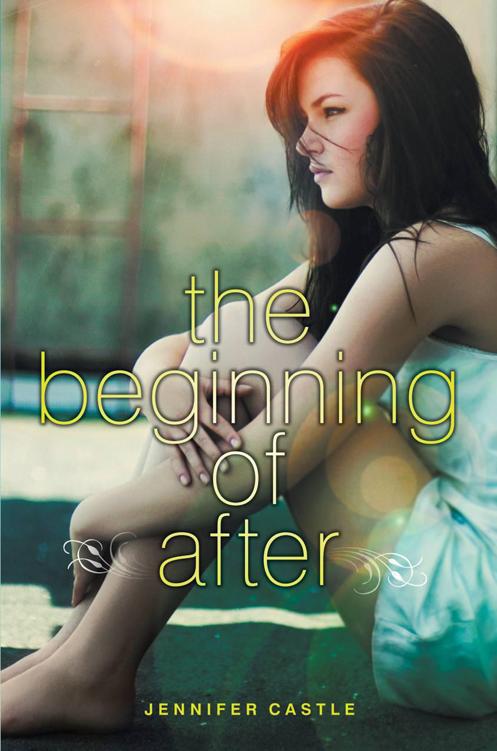

The Beginning of After

She’d offered to drive and wrote a note getting me out of school and work for the day, and made sure she got excellent directions from David’s grandparents. And here the flowers gave me something to do with my hands.

Now Nana was shopping at some nearby mall—she couldn’t stand these places, she’d seen too many of her friends die in them—and I was alone in the Peach Palace.

“Of course, sweetie. They smell lovely. He’ll like them, I’m sure.”

The nurse got up and motioned for me to follow her, down another long hallway. At the very end I could see a huge picture window with sunlight streaming in, and I had a sudden urge to take off running, running, until I could crash through the glass headfirst into freedom.

“Here we are,” she said. She knocked twice on a door that was slightly ajar, paused, then opened it all the way. “I’ll leave you two alone, but please let me know if you need anything. I’ll be back in a few minutes with a vase and some water.”

I peeked slowly around the door and first saw furniture—a dark wooden dresser, an overstuffed flowered armchair. Then a bright window draped in gauzy white curtains, the sun coming through so strong I almost had to look away from it. Next, a machine that whirred and beeped quietly but intensely, and the rising and falling chest of Mr. Kaufman, moving to the beat of what I realized was his respirator.

I came all the way into the room and looked at the carved wooden headboard of his bed, his navy blue pajamas with white piping, his closed, frozen eyes. The wedding band on his left hand and the framed photograph of himself, Mrs. Kaufman, and David peering down on him from the nightstand. I recognized it as their holiday card photo from two years ago, posed on a ski slope somewhere, all three of them making the kind of face that could either be a smile or just squinting into the sun.

I stood over him for a minute, watching this robotlike sleep he was in—the respirator even made it sound like he was snoring—and reminded myself of why I hated him. This jerk , I thought. This jerk who had all that scotch at seder and killed my parents. Killed my little brother, just a kid who still liked making fart noises with various parts of his arms. Ruined my life. Not to mention what he did to his own wife and son.

You got what you deserved, and now you’re basically broccoli.

There was a knock on the door again, and the nurse came back in with the vase. She placed it on the nightstand behind the photograph and smiled at me as I handed her the flowers.

“You said he’ll like them,” I asked. “Can he smell?”

“That depends who you ask,” she said as she lowered the flowers into the water. “A doctor might tell you no, Mr. Kaufman can’t smell anything because he’s in a vegetative state.” She glanced up at Mr. Kaufman’s face. “But if you ask me, he looks better when there’s something new in the room. Something pretty or that smells good. I noticed it once when his mother came in wearing a very strong perfume.”

The nurse moved to leave and I almost stopped her. But she was out the door fast and I was once again alone with the sleeping man and the loud machine. I’d lost the thread of that anger and now just felt nervous, so I sat down in the armchair and started saying the first things that came to mind.

“Hi, Mr. Kaufman,” I said. “It’s me, Laurel Meisner.”

I paused, like I expected him to answer. Just one of those things you do because you’re trained to do it.

“I saw David. He was planning on visiting you, but he got a job opportunity and had to leave really fast.”

I considered adding, Actually, your son ran away from something. I hope it wasn’t me.

What would David have told his father, if he’d come?

“Your parents sold the house. I hear it’s a young couple with a baby. It’s a great house for a family who’s just starting fresh. I think there are some other babies in the neighborhood, so that’ll be good, like a whole new generation of kids.”

I thought of David and Toby and me, of Megan and her sister Mary, Kevin McNaughton, and the Henninger twins, who now went to some private Catholic school and nobody ever saw anymore. A whole crop of children on two little streets, getting big and moving on. We grew into ourselves and away from simply being neighbors who all liked lawn sprinklers and swing sets.

I was stuck again for something to say. Just talk! He can’t hear you

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher