![The Chemickal Marriage]()

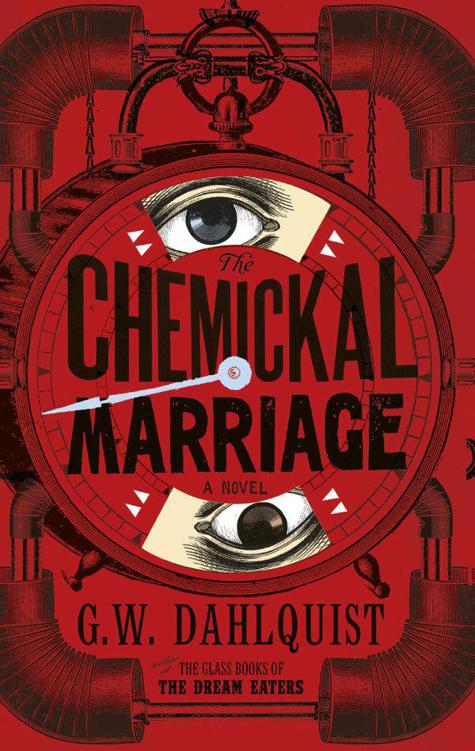

The Chemickal Marriage

given

you

pain. Your brothers are safe at home.’

‘I know how my brothers are.’

‘Have you visited them?’

The girl looked away.

‘No. Do you see? You

don’t

know – you have been

told

. What else have you trusted that woman to say?’ Miss Temple stood, rearranging her petticoats, and indicated the chamberpot. Again the girl shook her head. ‘It will be a long journey,’ said Miss Temple, annoyed that she had come to parrot every exasperating aunt or guardian she had ever known. With a shrug the girl took her place on the chamberpot, gazing sullenly at a point between her shoes.

‘The Contessa sent you to my hotel,’ said Miss Temple. ‘You did not try to go home.’

‘Why should I have done that?’

‘Because she is extremely wicked.’

‘I think

you’re

wicked.’

The retort flung, Francesca squirmed on her seat and said nothing. Francesca’s face was naturally pale, but now it was pinched and drawn. Had the girl been eating? Miss Temple imagined the woman flinging scraps at Francesca’s feet with an imperious sneer – but then recalled her own experience in the railway car, the Contessa breaking a pie in two, passing bites of a green apple with an insidious amity.

‘So the Contessa is your friend,’ she said.

Francesca sniffed.

‘She is very beautiful.’

‘More beautiful than

you

.’

‘Of course she is. She is a black-haired angel.’

Francesca looked up warily, as if ‘angel’ had a meaning she did not expect Miss Temple to know. Miss Temple put one gloved finger beneath Francesca’s chin and held her gaze.

‘I know it is frightening to be alone, and lonely to be strong. But you are heir to the Trappings, and heir to the Xoncks. You must make up your

own

mind.’

She stepped back and allowed the girl to stand. Francesca did so, the dress still gathered at her spindled thighs. ‘There is no water,’ she said plaintively.

‘I did without water perfectly well,’ muttered Miss Temple, but she opened her clutch bag and dug for a handkerchief. With a grunt she tore it in half, then in half again, and held the scrap to Francesca, who snatched it away and hunched to wipe.

‘A soldier does not need someone’s handkerchief,’ observed Miss Temple.

‘I am not a soldier.’

Miss Temple took the girl’s arm and steered her to the door. ‘But you

are

, Francesca. Whether you want to be or not.’

‘You are returned, excellent.’ Doctor Svenson rose to his feet, working both arms into his greatcoat, a lit cigarette in his mouth. Chang stood across the room. Miss Temple perceived the shift in each man’s posture at her entrance. They had been speaking of her. Her sting of resentment was then followed by an inflaming counter-notion, that they had

not

been speaking of her. Instead, at her entrance, they had ceased their discussion of strategiesand danger, matters to which she could neither contribute nor need be troubled by.

Despite his crisis Chang seemed every bit as able as before – and far more so than anyone imprisoned for weeks ought to be. One look at Svenson showed the man’s exhaustion. That he had been unable to kill the Contessa, of all people, was proof enough. Miss Temple resolved to help him as she could, just as a colder part of her mind marked him down as unreliable.

‘How best to return?’ asked Svenson. ‘The vestibule key allows us some choice –’

‘You don’t go

that

way.’ Francesca marched to the cupboard doors and pulled them wide. Inside was a metal hatch. ‘You need a lantern. There are rats.’

Svenson peered down the shaft. ‘And where does that – I mean, how far down –’

‘To the bridge,’ Chang answered. ‘The turbines.’

‘Ah.’

Miss Temple called to Chang. ‘Are you fully recovered?’

Chang spread his arms with a sardonic smile. ‘As you find me.’

‘Is that all you can say?’

‘I looked into something I should not have, like a fool.’

‘What did you see?’

‘What did

you

see? The Doctor described your ludicrous imitation.’

‘I looked in the glass ball to provoke the Comte’s memories – to learn how to help you.’

‘And in doing so only endangered yourself.’

‘But I discovered –’

‘What we already know. Vandaariff has made glass with different metals. The red ball figures prominently in his great painting, and thus no doubt is highly charged within his personal cosmology. An alchemical apple of Eden.’

‘But you –’

‘Yes,

I

have a foreign object near my

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher