![The Crowded Grave]()

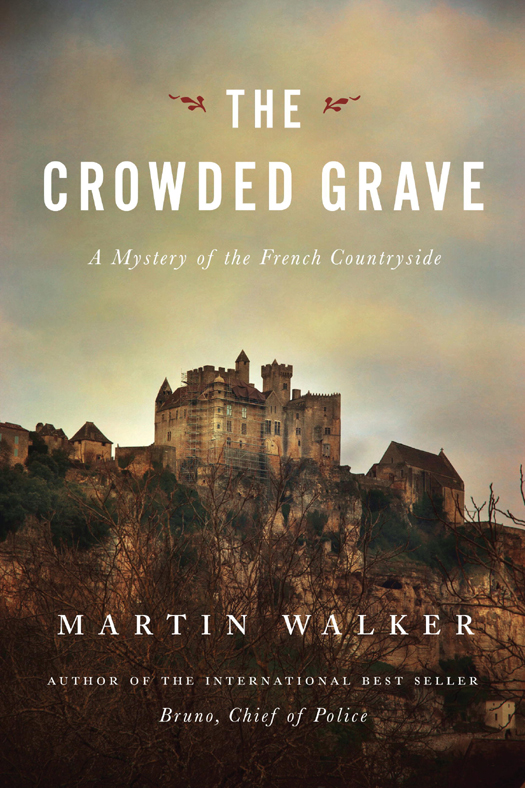

The Crowded Grave

the lives of the British in Périgord.

“Let me check connections to Edinburgh and call you back. I want to get there tonight so I may have to go via Bordeaux or Paris. I don’t know how long I’ll be gone,” Pamela said, her voice tense with dismay.

“Have you managed to speak to the hospital?” he asked.

“No, just to my aunt so far, but she had a brief meeting with the doctor and she’s at the hospital. It’s so unfair. She’s only in her sixties, never had a day’s illness and now this. Can you look after the horses? It might be easier if you and Gigi moved into my place …”

“Don’t worry, we’ll work it out,” he said, trying to calm her. Bruno had never heard Pamela like this, her voice gabbling, jumping from subject to subject. She must be in shock herself. “The important thing now is to get you there. Let me know about the flight times and I’ll drive you wherever you need to go.”

Part of his mind was wondering whether he’d be able tokeep that promise, with security meetings and bombings, foie gras and Horst’s disappearance, the mayor and horses all clamoring for his attention.

“I’m very sorry about your mother. I hope she recovers soon. What time did it happen?”

“That’s just it. We don’t really know,” said Pamela, her voice cracking. Bruno heard her swallow hard. “They think it was sometime yesterday evening. She was in her normal clothes, and her bed hadn’t been slept in. If my aunt hadn’t arranged to visit her for coffee this morning she might have been lying there another day.”

“Are you alone now?” he asked.

“Yes, but I’m okay. I’ll get onto the Internet and call you back.” Pamela hung up, and Bruno, ignoring the buzz of an incoming text message, quickly rang Fabiola at the clinic to tell her the news and ask if she could go and keep Pamela company. Fabiola promised to go as soon as her last morning appointment was finished, probably not long after eleven.

18

Although it was the smallest of the security committee meetings so far, for the first time the video conference link with the ministry in Paris was being used, and Bruno looked at the brigadier’s familiar face on the screen with interest. Most unusually, the brigadier was smiling.

His voice was normal, but his image on screen kept jerking in a disconcerting way as he explained that Horst’s name had raised an alarm in Berlin. Bruno was startled to learn that the quiet archaeologist had been a student militant in the sixties and a suspected sympathizer with the Red Army Faktion in the seventies. Isabelle gasped when the brigadier said that Horst had a brother called Dieter, now believed dead, who was an associate of the Baader-Meinhof Group and possibly even an active member. The brother got to East Germany, and the Stasi files reported him dying of a heart attack in 1989, the year the Wall came down. There were no specific links to ETA from his known record, although there was a well-documented history of cooperation between ETA and the Red Army Faktion.

“This Dieter was known to have attended a Palestinian training camp in the Beka’a Valley in the seventies, at a timewhen several ETA militants were there,” the brigadier said, and looked up from the file. “I think we have a connection.”

“Perhaps Señor Gambara can get us some more information on this,” Isabelle interjected.

“We never came up with much on this so-called cooperation,” Carlos said. “There were personal contacts and some visits, stemming from those training camps in Libya and Lebanon, but no real collaboration. No joint operations, no sharing of munitions, nothing useful that we could get hold of. Remember those Palestinian training camps were over thirty years ago. But if you can get me the name of the camps and the dates, we’ll check from our side.”

“Our German colleagues have also tracked the father’s war record for us,” the brigadier went on. “He was Waffen SS, the military arm, and served his entire war in the Totenkopf armored division, which spent most of its time on the Eastern Front.”

“But there was a photo of him in France, on a tank with a Dunkerque signpost,” Bruno objected.

But that had been in 1940, when Heinrich Vogelstern was a junior officer, an Untersturmführer, the brigadier explained. After the fall of France his unit was stationed south of Bordeaux near the Spanish frontier until April 1941. Then they were moved to the east, to take part in the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher