![The Lesson of Her Death]()

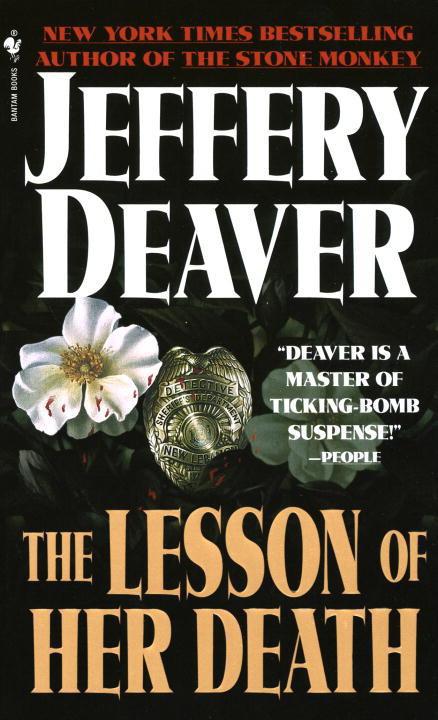

The Lesson of Her Death

looked at him with a surprised stare. Neither spoke as he walked past.

In his outer office Gebben accepted the hug of his tearful secretary.

“You didn’t …” she began. “I mean you didn’t need to come in today, Mr. Gebben.”

He said softly, “Yes I did.” And then escaped into his own sanctum. He sat in a swivel chair and looked out over a weedy lot surrounded by razor-wire-topped chain link and an abandoned siding.

Gebben—this stocky bull of a man, a Midwesterner with a pocked face, founder from scratch of Gebben Pre-Formed Inc., a simple man able to make whip-crack decisions—today felt paralyzed. He needed help, he had prayed for it.

He now spun slowly in his chair and watched the man who was going to provide that help walk up to his office door. A man who was cautious and respectful but unafraid, a man who had an immense physical presence even among big men. This man stood in Gebben’s doorway, patient, his own huge shoulders slumped. This was the only man in the world Gebben would leave his daughter’s wake to meet. The man entered the office and, when invited to, sat in an old upholstered chair across the desk.

“I’m very sorry, Mr. Gebben.”

Though Gebben did not doubt the sincerity of these words they fell leaden from the man’s chapped lips.

“Thank you, Charlie.”

Charles Mahoney, forty-one years old, was six three and he weighed two hundred and eighty pounds. He had been a Chicago policeman for thirteen years. Five years ago a handcuffed felony-murder suspect in Mahoney’s custody had died when two of the man’s ribs broke and pierced his lung. A perfect imprint of the butt of a police service revolver had been found on the suspect’s chest. Mahoney couldn’t offer any suggestions as to how this freak accident occurred and he chose to resign from the force rather than risk letting a Cook County grand jury arrive at one very reasonable explanation.

Mahoney was now head of Gebben Pre-Formed’s Security Department. He liked this job better than being a cop. When people were found inside the chain link or in the warehouse or in the parking lot and they got impressions put on their chests and their ribs broken, nobody gave a shit. Except the people with the broken ribs and Mahoney could tell them point blank to shut up and be happy that their ribs were the only things broken. They were rarely happy. But they did shut up.

Richard Gebben, who by fluke of age had missed military service, knew the Chicago story about Mahoney because the security chief was Gebben’s surrogate platoonbuddy. They drank together on occasion and told war stories and travel stories, though most of them involved Mahoney talking and Gebben saying, “It must’ve been a fucking great time,” or, “I’ve really gotta do that.” Gebben always picked up the check.

Gebben now held Mahoney’s eyes for a moment. “I’m going to ask you to do something for me, Charlie.”

“Sure, I’d—”

“Let me finish, Charlie.”

Mahoney’s eyes were on a toy truck that Gebben’s Human Resources Department passed out at Christmas. On the side of the trailer was the blue company logo. Mahoney didn’t have any kids so he’d never been given a truck. This irked him in a minor way.

“If you agree to help me I’ll pay you ten thousand dollars cash. Provided—”

“Ten thousand?”

“Provided that what I’m about to tell you never leaves this room.”

S he put the words one right after another in her mind. She said them aloud. “‘As virtuous men pass mildly away / And whisper to their souls to go …’”

The girl lay in the single bed, on top of a university-issue yellow blanket, under a comforter her mother had bought at Neiman-Marcus. The room lamps were out and light filtered through the curtains, light blue like the oil smoke of truck exhaust. Tears escaped from her eyes, saliva dripped onto the blanket beneath her head.

She remembered the last thing Jennie Gebben had said to her.

“Ah, kiddo. See you soon.”

Emily Rossiter spoke in a frantic whisper, “‘Whilst some of their sad friends do say, / The breath goes now and some say no.’”

They weren’t working. The words were powerless. She rested the book on her forehead for a moment then dropped it on the floor. Emily, who was twenty years oldand intensely beautiful, had a large mass of curly dark hair, which she now twined compulsively around her fingers. She recited the poem again.

At the knock on the door she inhaled in

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher