![The Mao Case]()

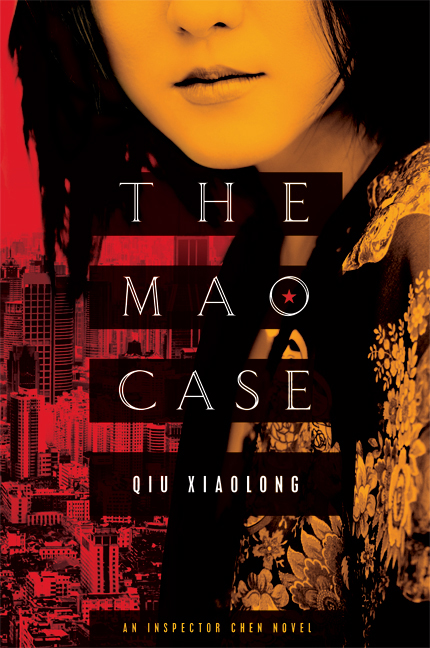

The Mao Case

revolutionary flame sweeping over the world.

But there was no market value for Mao poetry in the collective revival. No publishing house showed any interest in Long’s

revised edition, despite his passionate speeches and protests, both in and out of the Writers’ Association.

That was not the only trouble for Long. In the last few years, the Writers’ Association had suffered several cuts in their

government funding. People began to talk about reforming the system of “professional writers.” In the past, those acknowledged

as professional writers could get their monthly pay from the association until retirement, regardless of their publications.

Now a contract period was suggested, with each member’s qualifications being examined and determined by a committee. Long

was desperate, beginning to write something like short anecdotes — totally unrelated to Mao — in his effort to remain in the contract.

Chen happened to remember Long because of such a short piece published in

Shanghai Evening

. It was a vivid anecdote about river crabs, but “politically incorrect” in the judgment of the committee of the Writers’

Association, of which Chen was a member. So he dug the newspaper out and began rereading it. For a change, he added half a

lemon and a spoonful of sugar into his tea.

Several years before the economic reform started in the eighties, my old neighbor, Aiguo, a Confucianist middle school teacher

disappointed with the political banishment of Confucius from the classroom, began to develop a crab complex. He made a point

of enjoying the Yangchen river crabs at least three or four times during crab

season. His wife having passed away, his son having just started working in a state-run steel plant and dating a girl, Aiguo

justified his one and only passion by making reference to well-known writers like Su Dongpo, a Song-dynasty poet, who declared

a crab feast the most blissful moment of his life, “Oh that I could have crabs with a wine supervisor sitting beside me,”

or like Li Yu, a Ming-dynasty scholar, who confessed that he wrote for the purpose of making the crab-money — his life-saving

money. As an intellectual immersed in what “Confucius says,” Aiguo had to restrain himself from lecturing about the sage in

public, but he followed Confucius’s ritualistic rules for crab-eating at home.

“Do not eat when the food is rotten; do not eat when it looks off-color; do not eat when it smells bad; do not eat when it

is not properly cooked; do not eat when it is off season; do no eat when it is not cut right; do not eat when it is not served

with the appropriate sauce… Do not throw away the ginger… Be serious and solemn when offering a sacrifice meal to one’s ancestors…”

Aiguo would quote from the Analects by Confucius at the dinner table, adding, “It’s about the live Yangcheng crabs — all the

necessary requirements for them, including a piece of ginger.”

“All are excuses for his crab craziness. Confucius says,” his son commented with a resigned shrug to the neighbors, “don’t

believe him.”

Indeed, Aiguo had such a weakness, suffering a peculiar syndrome with the western wind rising in November, as if his heart

were being pinched and scratched by the crab claws. He had to conquer the craving with “a couple of the Yangcheng river crabs,

a cup of yellow wine,” and only then would he be able to work hard for the year, full of energy to throw himself into what

ever “Confucius says,” until the next crab season.

Aiguo retired at the beginning of the economic reform. The price of crabs had rocketed and a pound of large crabs cost three

hundred yuan. For an ordinary retiree like him, a pound of crab cost more than half of his monthly pension. Crabs became a

luxury affordable

only for the newly rich of the city. For the majority of the Shanghai crab eaters, like Aiguo, the crab season became almost

a season of torture.

In the same shikumen house lived Gengbao, a former student of Aiguo’s. Gengbao hardly acknowledged Aiguo as his teacher, for

he had flunked out of school, having received a number of Ds and Fs from Aiguo himself. As it is said in Taodejing, “In misfortune

comes fortune”: because of his failure at school, Gengbao started his cricket business in the early days of the reform and

became rich. In Shanghai, people gamble on cricket fights, so a ferocious cricket could sell for thousands of yuan.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher