![The Moment It Clicks: Photography Secrets From One of the World's Top Shooters]()

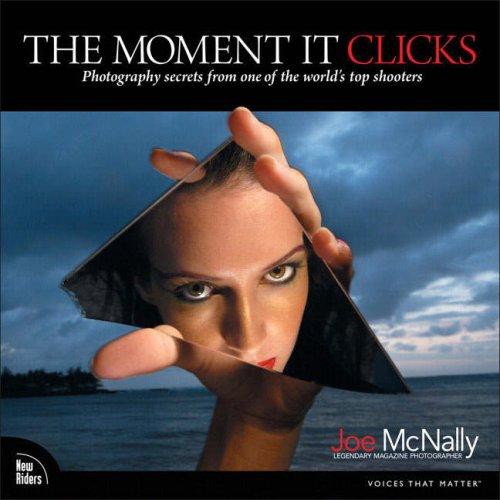

The Moment It Clicks: Photography Secrets From One of the World's Top Shooters

field beats a good day at the office, anytime. There are days that test this proposition. I once destroyed five motor-driven Nikons in one day. That was a bad day in the field.

When shooting a space shuttle launch, you are relying mostly on cameras you can’t be with or near. They’re called remotes, and you put them in the field 24 hours in advance of liftoff, rigged with devices that will trigger them (hopefully) at the right time. At launch time, you’re miles away, shooting a 1000mm lens through the heat waves. Lots of luck with that.

I put nine cameras in the field—the field being the saltwater estuary surrounding the launching pads at Cape Kennedy. I had high hopes.

A storm hit before liftoff. One of the worst I’d ever seen. All the photographers begged NASA to go back out and see what was left of their stuff. It was a camera graveyard out there. Grown men were crying. In my case, the only evidence of one of my rigs was three inches of tripod leg sticking out of the flooded swamp. I waded in up to my neck, eyeballing alligator warning signs, trying to haul my gear up from the muck.

Seeing as I was already in the swamp, I tried to get out some of the other shooters’ gear as well. They were standing on the bank, giving me directions. Since they were from the South, I asked if any of them knew whether a big storm got the gators riled up and made them more active. An answer came back: “Don’t you worry. Y’all just go get our stuff.” Probably the best use they’d ever seen for a Yankee.

My last rig was damaged, but not destroyed. I had one clean, dry 50mm lens in my pocket. I rewired that camera, popped the lens on, and patted it for luck. It was still pouring, and I figured I was just SOL. Turns out, the camera fired. Got a picture that ran as the cover of the year in a science issue for Discover , and it saved my butt.

The hard part was still to come. I had to call Al Schneider, cigar-chomping manager of the Time Life photo equipment area, to tell him I just destroyed a good chunk of the company’s pool photo gear. The cameras were in a garbage can in my shower at the Days Inn, being flushed with fresh water, when I called. Al chuckled. “I got the perfect solution for ya, kid,” he said. My heart skipped a hopeful beat. “Yeah,” he went on. “Deeper water.”

It’s a Rocky Road to Freelanceville

“Gosh, you mean after I get approved by a bunch of 20-year-olds, and I shoot it for free, I might get to use it after six months? Where do I sign up?”

My studio manager got this not too long ago from a magazine:

“Thanks very much for your email. It looks like before confirming this, both of our ends have to check on remaining details, i.e., our whole creative team has to agree on contracting Joe. Additionally, while we are happy to take care of the production legwork—i.e., getting the talent, clothes, makeup and styling, location scouted, and permission acquired—we generally do not offer a fee for photography. Unfortunately, with the increase of our circulation came staggering print cost increases. It is a large shot (virtually a full page), however, and a dynamic image. I will also get back to you ASAP with regard to usage, but I imagine that he will be able to publish it wherever he likes after 6 mos. time.”

Gosh, you mean after I get approved by a bunch of 20-year-olds, and I shoot it for free, I might get to use it after six months?

Where do I sign up?

One of the new road signs to Freelanceville.

Photo © Brad Moore

Be a Pest

I was shooting a Time cover on the launch of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Disney being Disney, they jumped into the zoo business with both feet, scouring zoos everywhere and buying up bunches of animals.

It was a cover story, so there was a lot of pressure. I needed certain things to happen which weren’t happening.

The main attraction was the safari ride, which I was told I had to shoot from the safari vehicles on the established path of the ride. No exceptions. I told them this was impossible. How do you shoot a picture of something you’re sitting on?

I also wanted to shoot behind the scenes with the animals, to show how they were being cared for. Disney didn’t want to show the animals behind bars. They wanted the public to believe that at night, the animals were being cared for by Mickey and Tinker Bell, and instead of being caged, they were chatting amongst themselves and hanging around at

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher