![The Night Listener : A Novel]()

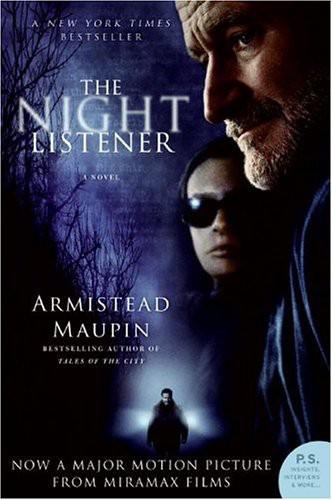

The Night Listener : A Novel

became convinced she was being investigated by St. Michael’s Church—by the Ladies’ Auxiliary, no less. “They think I’m an alcoholic,” I heard her tell my parents one night, and even then I guessed that this delusional nonsense was really about my grandfather and the firestorm of speculation that Dodie must have endured after his suicide. I had come across a bundle of old letters in the attic several years earlier: proclamations from local civic organizations extolling the virtues of the first Gabriel Noone upon his untimely death. Though they all avoided the particulars, there was a tone of anxious overstatement to them that invited suspicion even before I knew how my grandfather had died. In its concerted effort to remove the shame, the town had merely made it official. And Dodie had borne it for almost a quarter of a century. I remember passing her room late one night and hearing a sound that rattled me to the core. At seventy-five she was whimpering in her sleep like a baby, curled up there in the big mahogany sleigh bed that her grandfather’s slaves had built.

My mother took care of everyone, but her firstborn was especially blessed. When I was as young as eight, she would bring me breakfast in bed on Saturday mornings, so I could listen to Big John and Sparky in the alpine lair of my upper bunk. My father, who complained bitterly of her “mollycoddling,” had contributed to this indulgence by building a shelf near the ceiling that could hold both my short-wave radio and my vast collection of Hardy Boys books. Later, when I discovered The Big Show and its host, Miss Tallulah Bankhead, I would climb to my aerie after supper and surrender to the smoky-warm, mannish voice of a woman I worshipped as a goddess but had never actually seen.

In Mummie’s version of things I was simply her eccentric child.

My brother, Billy, was the athletic, methodical one, the natural heir to my father’s gift for finance, a lively, uncomplicated kid who spent hours moving marbles across the rug as if they were beads on an abacus. And Josie, by definition, was the Precious Little Girl, a role so exalted that no one could imagine a future for her beyond marriage and motherhood. Of the three children, I was the puzzlement: the one my mother dubbed Ferdinand, since, unlike the other little bulls, I preferred to sit alone in the pasture and smell the flowers.

How could she not have known from the beginning? She must have suspected something when I saw Singin’ in the Rain eight times at the age of ten, when I entered my homemade vegetable dyes in the junior high science fair, when I spent weeks designing a stained-glass window for my bedroom.

“Gabriel is just naturally creative,” Mummie would tell her friends, when Pap wasn’t there to hear it. “One day he’ll write a scandalous book that will embarrass the whole family. Just the way Tom Wolfe did.” My mother had grown up in Asheville when Wolfe was wreaking havoc there with Look Homeward, Angel . She recalled the way the author’s family had dined out for years on their literary notoriety. Old Mrs. Wolfe had always been ready with a stock reply when asked how it felt to have her dirty laundry aired in public.

Drawing herself up grandly, she would proclaim with a stoic sigh that “Caesar had Brutus, and Jesus had Judas, and we have our Tom.” But Wolfe was permitted his indiscretion, Mummie said, because he was a genius and a true bohemian; he had run off to the North, you see, and moved in with a Jewess who was much older than he was. You couldn’t get any more bohemian than that, she said with a knowing look, as if to suggest that there might be a Jewess or two in my own future.

Though she played by the rules of Charleston society, my mother herself nursed private dreams of bohemianism. Her own mother had been an ardent suffragist in England and was still known to read palms and cite the theosophy of Madame Blavatsky. So Mummie would often make reference to karma and rosy circles and past lives, without fully knowing what those things were, and certainly without abandoning her weekly Episcopal prayer group. But I wanted her to be Auntie Mame as much as she did, so I egged her on at every turn. We went flea marketing together and bought exotic Indian cotton bedspreads for the house. Once, in a rare display of physicality, I completely rearranged the living room to showcase more dramatically her fine collection of blue Pisgah Mountain

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher