![The Night Listener : A Novel]()

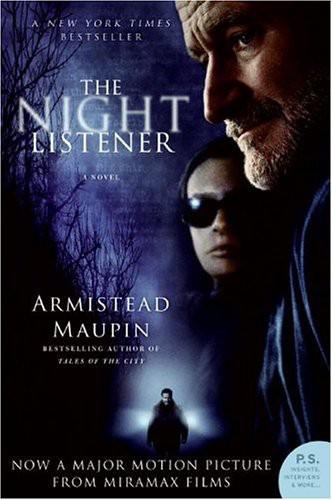

The Night Listener : A Novel

Hitchcock movies and old houses, and she thought we might enjoy each other.

Pap and I slept on her floor that night. At least I think we did. I’ve told this story so often that there may have been some bejewelling over the decades. Maybe I just meant it metaphorically back then—it’s hard to imagine what we would have used for bed-ding—but I do know that we stayed until dawn, camped out like Gypsies in defiance of the nurses’ orders. My mother wasn’t expected to die that night, so Billy and Josie had gone home to their kids, and the old man and I were left alone—on the floor or in chairs or somewhere—talking quietly while the patient slept.

And there, against the sound track of my mother’s labored breathing, my father said something unexpected: that he’d known I was gay—or sensed it, at least—since I was a child, and that he was sorry he hadn’t brought it up earlier and made life easier for me. I didn’t know what to say except to thank him. Pap had never even used the word gay before, and this was closer than he’d ever come to addressing my needs. This must be how it feels, I thought, to be close to your father, to receive his love without the burden of conditions. It didn’t occur to me until later, when the funeral was over and I was back in San Francisco, that this sweetest of paternal moments may have been orchestrated by the woman sleeping next to us. And sometimes I wonder if she was even asleep.

All this was on my mind that snowy night in Wysong, not because I had some prescient sense of what was already happening in Charleston—I didn’t—but because I was thinking about the bond between mothers and sons. Some mothers would do anything for their boys; mine would have, certainly, and did. And had I confessed that I was a serial killer, say, instead of a run-of-the-mill homosexual, Laura Noone would have dealt with that too, sooner or later. She would have found a way in her boundless heart to make me the sweetest, most misunderstood serial killer in the world.

Donna and Pete had a bond like that, I knew, a love so strong that it lay well beyond the strictures of ordinary morality. And that scared me a little as I set off into the night, following a star to a child I’d never met.

TWENTY-TWO

SNOW BLINDNESS

A WISE MAN would have waited until morning. It was pitch-black outside, and I already knew how hard it was to find my way around town in the snow. But I remembered Pete’s description of that derelict water tank, and how you couldn’t see the star from his bedroom, and how the light spilled over to accentuate the graffiti, and I knew that most of those things would be difficult—if not impossible—to determine in daylight.

No one could argue that I was acting rationally that night. Somehow I’d lost my perennial sense of authorship. What had begun as a simple mind game, a troubling diversion, had become the only universe I knew, as if I’d been reduced to a mere character in the story.

As if someone else was controlling the plot.

Finding the water tank was the easy part. The desk clerk’s directions—and the star itself—led me there in a matter of minutes. A gross brown onion on rusty legs, it was just as lethal-looking as Pete had described, with a Cyclone fence and an ugly coil of concertina wire to keep off the inmates of the junior high school. The neighborhood itself was residential and early twentieth century—close to what I’d imagined—though my heart sank when I realized how many of these little houses commanded at least a partial view of the water tank. I climbed from the car and turned up my collar against the snow. Then, gazing up at the pulsing blue ember of the star, I circumnavigated the tank until only the faintest haze could be seen creeping around its side. All the while I murmured this mantra under my breath: Roberta Blows, Roberta Blows, Roberta Blows .

I could make out a few indefinite scribblings, the sort of fat-lettered tagging you find all over the world. Seeing them I pictured Pete in his oxygen tent, peering up dolefully at the terrible proof that other kids could fly. I sighed at the thought, even as I realized that Roberta was nowhere to be seen. Maybe, then, I’d find her on the other side; the light, after all, had to spill in both directions. So I walked back to the star and kept walking until it was once again eclipsed by the tank. There was much more graffiti on this side, the side that could be seen from the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher