![The Night Listener : A Novel]()

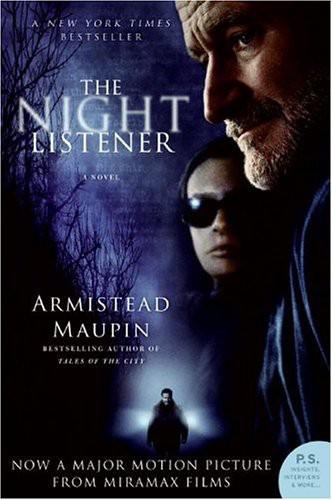

The Night Listener : A Novel

secrets.

She carried mine long before I knew that she knew. Her early suspicions were confirmed by a girlfriend of mine—a friend, really, nothing more—who had flown out to San Francisco in the preposterous belief that I had seen the light and was ready to propose. All I’d wanted, in fact, was a generous listener, someone from home to witness my fledgling joy, to hear about this handsome doctor I’d met, this stalwart professional that even Pap would find acceptable.

Becky Ravenel listened all right, her mouth slightly agape, pausing only to slip a Valium from her purse and gobble it dry like an after-dinner mint. The next day, when I was off at the radio station writing ads for waterbeds and singles bars, she phoned Charleston to break the news to the mother-in-law she would never have.

Mummie, mind you, never told me this. She harbored the knowledge for three or four years as that malignancy grew in her breast.

She wasn’t shocked, she told Josie later, but she was worried about the way the world would treat me, and the life I’d lead later. Maybe it seemed all right now, when I was young and reckless, but what would it be like when I was older, when I was fifty, say, and lonely and childless? She was just as worried about my father, resolving to keep the news from him at any cost, knowing how it would destroy him. But she did her best to educate herself, spending hours in the stacks of the Charleston library furtively reading books she was too ashamed to check out.

The following summer my folks came to visit. I wanted them to see, if not the whole truth of my life, at least the effects of that truth: my charming little house on a rooftop, my circle of presentable friends, my blazingly evident happiness. I wanted them to feel what I’d been feeling in the hope that it might transform them, force them to see the rightness—the staggering simplicity—of this thing that I’d feared so foolishly for most of my life.

So we took a drive up the coast, winding our way up Highway 1, where the golden hills and sparkling bays were certain to make my father a mellower man. Just outside Bolinas I spotted a teepee in the middle of a meadow. I had been to this place the month before, had met its occupants, in fact, and thought they would make the perfect field trip for my parents’ first visit to Lotusland. Explaining nothing, I led them across the meadow—Pap in a business suit, Mummie in her black wet-look trench coat—and yelled out a greeting to the teepee. Within seconds, a lion-haired kid of twenty had emerged, soon to be flanked by his tentmates, tawny girls in stretched-out Tshirts—two of them—braless as the day they were born. When I asked if they’d mind visitors, they invited us in for chamomile tea.

My folks handled it beautifully at first. Pap surveyed the teepee in silence, chuckling to himself, then finally declared it the damnedest thing he’d ever seen—his highest accolade. He asked questions about their water supply and what they used to protect their food from predators, and even made a sly joke about the utterly benign herbs drying above him on strings. Mummie exclaimed over the tea and the loveliness of the lagoon shimmering in the distance.

And our hosts were so gracious, so courtly in their sweet hippie way, that I believed I’d pulled off something wonderful: a meeting of polar opposites that had somehow altered everyone for the better.

Once we were back in the car, heading north to the Russian River, I could sense the sea change. Pap was quiet at first, then began to mutter about draft dodgers and degenerates, worthless little free-loading bastards who had never learned the value of hard work. I’d been trained not to argue with him, but it incensed me that he could be so charming and tolerant one moment and so bitterly condemning the next. I said as much, questioning his right to judge people he didn’t know, just because they were different, just because they weren’t like him. He called me a damn fool idiot, and his face turned dangerously red, and it just escalated from there.

I stood my ground as never before; at thirty I was sick of his tantrums, tired of playing my mother’s old game of placation and retreat. This wasn’t about hippies, after all, at least not for me; it was about becoming my own version of Gabriel Noone, though I’d never actually suggested what that might be. On my father’s part, there may have been something else at play, something to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher