![The Rembrandt Affair]()

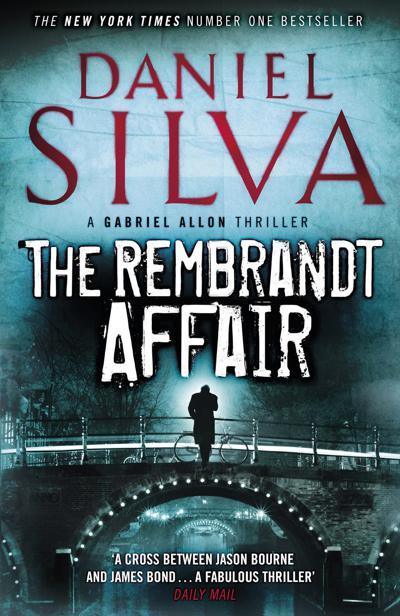

The Rembrandt Affair

existence.

“There were one or two paintings that were mildly interesting, but the rest was complete crap. As I was leaving, my mobile rang. It was none other than David Cavendish, art adviser to the vastly rich, and a rather shady character, to put it mildly.”

“What did he want?”

“He had a proposition for me. The kind that couldn’t be discussed over the phone. Insisted I come see him right away. He was staying at a borrowed villa on Sardinia. That’s Cavendish’s way. He’s a houseguest of a man. Never pays for anything. But he promised the trip would be well worth my time. He also hinted that the house was filled with pretty girls and a great deal of excellent wine.”

“So you caught the next plane?”

“What choice did I have?”

“And the proposition?”

“He had a client who wanted to dispose of a major portrait. A Rembrandt. Quite a prize. Never been seen in public. Said his client was disinclined to use one of the big auction houses. Wanted the matter handled privately. He also said the client wished to see the painting hanging in a museum. Cavendish tried to portray him as some sort of humanitarian. More likely, he just couldn’t bear the thought of it hanging on the wall of another collector.”

“Why you?”

“Because by the rather low standards of the art world, I’m considered a paragon of virtue. And despite my many stumbles over the years, I’ve somehow managed to maintain an excellent reputation among the museums.”

“If they only knew.” Gabriel shook his head slowly. “Did Cavendish ever tell you the seller’s name?”

“He spun some nonsense about faded nobility from an Eastern land, but I didn’t believe a word of it.”

“Why a private sale?”

“Haven’t you heard? In these uncertain times, they’re all the rage. First and foremost, they ensure the seller total anonymity. Remember, darling, one normally doesn’t part with a Rembrandt because one is tired of looking at it. One parts with it because one needs money. And the last thing a rich person wants is to tell the world that he’s not so rich anymore. Besides, taking a painting to auction is always risky. Doubly so in a climate like this.”

“So you agreed to handle the sale.”

“Obviously.”

“What was your take?”

“Ten percent commission, split down the middle with Cavendish.”

“That’s not terribly ethical, Julian.”

“We do what we have to do. My phone stopped ringing the day the Dow went below seven thousand. And I’m not alone. Every dealer in St. James’s is feeling the pinch. Everyone but Giles Pittaway, of course. Somehow, Giles always manages to weather all storms.”

“I assume you got a second opinion on the canvas before taking it to market?”

“Immediately,” said Isherwood. “After all, I had to make sure the painting in question was actually a Rembrandt and not a Studio of Rembrandt, a School of Rembrandt, a Follower of Rembrandt, or, heaven forbid, in the Manner of Rembrandt.”

“Who did the authentication for you?”

“Who do you think?”

“Van Berkel?”

“But of course.”

Dr. Gustaaf van Berkel was widely acknowledged to be the world’s foremost authority on Rembrandt. He also served as director and chief inquisitor of the Rembrandt Committee, a group of art historians, scientists, and researchers whose lifework was ensuring that every painting attributed to Rembrandt was in fact a Rembrandt.

“Van Berkel was predictably dubious,” Isherwood said. “But after looking at my photographs, he agreed to drop everything and come to London to see the painting himself. The flushed expression on his face told me everything I needed to know. But I still had to wait two agonizing weeks for Van Berkel and his star chamber to hand down their verdict. They decreed that the painting was authentic and could be sold as such. I swore Van Berkel to secrecy. Even made him sign a confidentiality agreement. Then I boarded the next plane to Washington.”

“Why Washington?”

“Because the National Gallery was in the final stages of assembling a major Rembrandt exhibit. A number of prominent American and European museums had agreed to lend their own Rembrandts, but I’d heard rumors about a pot of money that had been set aside for a new acquisition. I’d also heard they wanted something that could generate a few headlines. Something sexy that could turn out a crowd.”

“And your newly discovered Rembrandt fit that description.”

“Like one

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher