![The Rembrandt Affair]()

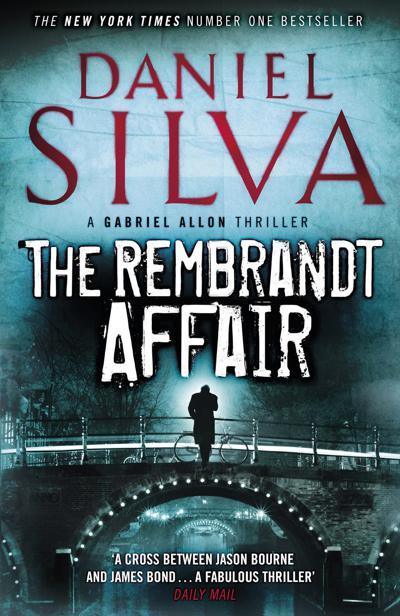

The Rembrandt Affair

attic. She remembered the hall had been in complete darkness. Even so, she had no trouble finding her way to the bathroom. She had taken those same seven steps, twice each day, for the past five months. Those seven steps had constituted her only form of exercise. Her only break from the monotony of the attic. And her only chance to see the outside world.

“There was a window next to the basin. It was small and round and overlooked the rear garden. Mrs. de Graaf insisted the curtain be kept closed whenever we entered.”

“But you opened it against her wishes?”

“From time to time.” A pause, then, “I was only a child.”

“I know, Lena,” Gabriel said, his tone forgiving. “Tell me what you saw.”

“I saw fresh snow glowing in the moonlight. I saw the stars.” She looked at Gabriel. “I’m sure it seems terribly ordinary to you now, but to a child who had been locked in an attic for five months it was…”

“Irresistible?”

“It seemed like heaven. A small corner of heaven, but heaven nonetheless. I wanted to touch the snow. I wanted to see the stars. And part of me wanted to look God directly in the eye and ask Him why He had done this to us.”

She scrutinized Gabriel as if calculating whether this stranger who had appeared on her doorstep was truly a worthy recipient of such a memory.

“You were born in Israel?” she asked.

He answered not as Gideon Argov but as himself.

“I was born in an agricultural settlement in the Valley of Jezreel.”

“And your parents?”

“My father’s family came from Munich. My mother was born in Berlin. She was deported to Auschwitz in 1942. Her parents were gassed upon arrival, but she managed to survive until the end. She was marched out in January 1945.”

“The Death March? My God, but she must have been a remarkable woman to survive such an ordeal.” She looked at him for a moment, then asked, “What did she tell you?”

“My mother never spoke of it, not even to me.”

Lena gave a perceptive nod. Then, after another long pause, she described how she stole silently down the stairs of the de Graaf house and slipped outside into the garden. She was wearing no shoes, and the snow was very cold against her stockinged feet. It didn’t matter; it felt wonderful. She grabbed snow by the handful and breathed deeply of the freezing air until her throat began to burn. She spread her arms wide and began to twirl, so that the stars and the sky moved like a kaleidoscope. She twirled and twirled until her head began to spin.

“It was then I noticed the face in the window of the house next door. She looked frightened—truly frightened. I can only imagine how I must have looked to her. Like a pale gray ghost. Like a creature from another world. I obeyed my first instinct, which was to run back inside. But I’m afraid that probably compounded my mistake. If I’d managed to react calmly, it’s possible she might have thought I was one of the de Graaf children. But by running, I betrayed myself and the rest of my family. It was like shouting at the top of my lungs that I was a Jew in hiding. I might as well have been wearing my yellow star.”

“Did you tell your parents what had happened?”

“I wanted to, but I was too afraid. I just lay on my blanket and waited. After a few hours, Mrs. de Graaf brought us our basin of fresh water, and I knew we had survived the night.”

The remainder of the day proceeded much like the one hundred and fifty-five that had come before it. They washed to the best of their ability. They were given a bit of food to eat. They made two trips each to the toilet. On her second trip, Lena was tempted to peer out the window into the garden to see if her footprints were still visible in the snow. Instead, she walked the seven steps back to the ladder and returned to the darkness.

That night was Shabbat. Speaking in whispers, the Herzfeld family recited the three blessings—even though they had no candles, no bread, and no wine—and prayed that God would protect them for another week. A few minutes later, the razzias started up: German boots on cobblestone streets, Schalkhaarders shouting out commands in Dutch.

“Usually, the raiding parties would pass us by, and the sound would grow fainter. But not that night. On that night the sound grew louder and louder until the entire house began to shake. I knew they were coming for us. I was the only one who knew.”

20

AMSTERDAM

L ena Herzfeld lapsed into a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher