![The Rembrandt Affair]()

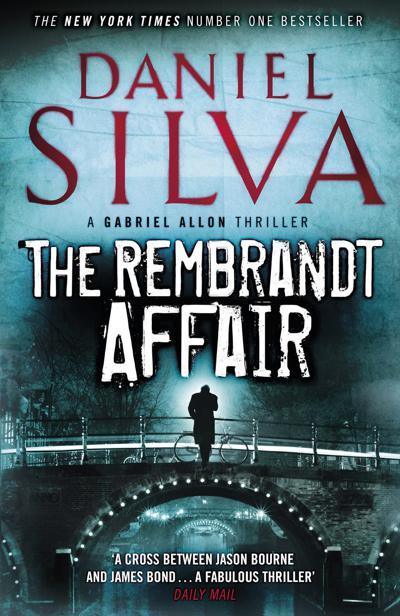

The Rembrandt Affair

forbidden to attend the theater, visit public libraries, or view art exhibits. Jews were forbidden to serve on the stock exchange. Jews could no longer own pigeons. Jewish children were barred from “Aryan” schools. Jews were required to sell their businesses to non-Jews. Jews were required to surrender art collections and all jewelry except for wedding bands and pocket watches. And Jews were required to deposit all savings in Lippmann, Rosenthal & Company, or LiRo, a formerly Jewish-owned bank that had been taken over by the Nazis.

The most draconian of the orders was Decree 13, issued on April 29, 1942, requiring Jews over the age of six to wear a yellow Star of David at all times while in public. The badge had to be sewn—not pinned but sewn —above the left breast of the outer garment. In a further insult, Jews were required to surrender four Dutch cents for each of the stars along with a precious clothing ration.

“My mother tried to make a game out of it in order not to alarm us. When we wore them around the neighborhood, we pretended to be very proud. I wasn’t fooled, of course. I’d just turned eleven, and even though I didn’t know what was coming, I knew we were in danger. But I pretended for the sake of my sister. Rachel was young enough to be deceived. She loved her yellow star. She used to say that she could feel God’s eyes upon her when she wore it.”

“Did your father comply with the order to surrender his paintings?”

“Everything but the Rembrandt. He removed it from its stretcher and hid it in a crawl space in the attic, along with a sack of diamonds he’d kept after selling his business to a Dutch competitor. My mother wept as our family heirlooms left the house. But my father said not to worry. I’ll never forget his words. ‘They’re just objects,’ he said. ‘What’s important is that we have each other. And no one can take that away.’”

And still the decrees kept coming. Jews were forbidden to leave their homes at night. Jews were forbidden to enter the homes of non-Jews. Jews were forbidden to use public telephones. Jews were forbidden to ride on trains or streetcars. Then, on July 5, 1942, Adolf Eichmann’s Central Office for Jewish Emigration dispatched notices to four thousand Jews informing them that they had been selected for “labor service” in Germany. It was a lie, of course. The deportations had begun.

“Did your family receive an order to report?”

“Not right away. The first names selected were primarily German Jews who had taken refuge in Holland after 1933. Ours didn’t come until the second week of September. We were told to report to Amsterdam’s Centraal Station and given very specific instructions on what to pack. I remember my father’s face. He knew it was a death sentence.”

“What did he do?”

“He went up to the attic to retrieve the Rembrandt and the bag of diamonds.”

“And then?”

“We tore the stars from our clothing and went into hiding.”

18

AMSTERDAM

C hiara had been right about Lena Herzfeld. After years of silence, she was finally ready to speak about the war. She did not rush headlong toward the terrible secret that lay buried in her past. She worked her way there slowly, methodically, a school-teacher with a difficult lesson to impart. Gabriel and Chiara, trained observers of human emotion, made no attempt to force the proceedings. Instead, they sat silently on Lena’s snow-white couch, hands folded in their laps, like a pair of rapt pupils.

“Are you familiar with the Dutch word verzuiling ?” Lena asked.

“I’m afraid not,” replied Gabriel.

It was, she said, a uniquely Dutch concept that had helped to preserve social harmony in a country sharply divided along Catholic and Protestant lines. Peace had been maintained not through interaction but strict separation. If one were a Calvinist, for example, one read a Calvinist newspaper, shopped at a Calvinist butcher, cheered for Calvinist sporting clubs, and sent one’s children to a Calvinist school. The same was true for Roman Catholics and Jews. Close friendships between Catholics and Calvinists were unusual. Friendships between Jews and Christians of any sort were virtually unheard of. Verzuiling was the main reason why so few Jews were able to hide from the Germans for any length of time once the roundups and deportations began. Most had no one to turn to for help.

“But that wasn’t true of my father. Before the war, he made a number of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher