![The Rembrandt Affair]()

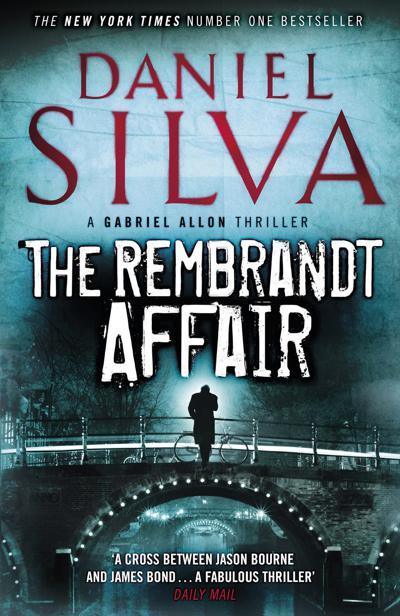

The Rembrandt Affair

finest while its international consultants provided entrée to firms wishing to do business in dangerous corners of the world. It operated its own private bank and maintained a vault beneath the Talstrasse used for storage of sensitive client assets. At last estimate, the value of the items contained in the vault exceeded ten billion dollars.

Filling Zentrum’s various divisions with qualified staff provided a unique challenge since the company did not accept applications for employment. The process of recruitment never varied. Zentrum talent spotters identified targets of interest; then, without the target’s knowledge, Zentrum investigators conducted a quiet but invasive background check. If the target was deemed “Zentrum material,” a team of recruiters would swoop in for the kill. Their task was made easier by the fact that Zentrum’s salaries and perks far exceeded those of the overt business world. Indeed, Zentrum executives could count on one hand the number of targets who had turned them down. The firm’s workforce was highly educated, multinational, and multiethnic. Most employees had spent time in the military, law enforcement, or the intelligence services of their respective countries. Zentrum recruiters demanded fluency in at least three languages, though German was the language of the workplace and was therefore a requirement for employment. Resignations were almost unheard of, and terminated employees rarely found work again.

Like the intelligence services it sought to emulate, Zentrum had two faces—one it reluctantly showed the world, another it kept carefully hidden. This covert branch of Zentrum handled what were euphemistically referred to as special tasks: blackmail, bribery, intimidation, industrial espionage, and “account termination.” The name of the unit never appeared in Zentrum’s files nor was it spoken in Zentrum’s offices. The select few who knew of the unit’s existence referred to it as the Cellar Group, or Kellergruppe, and its chief as the Kellermeister. For the past fifteen years, that position had been held by the same man, Ulrich Müller.

The two operatives Müller had sent to Amsterdam were among his most experienced. One was a German who specialized in all things audio; the other was a Swiss with a flair for photography. Shortly after six p.m., the Swiss operative snapped a photo of the trim Israeli with gray temples gliding through the entrance of the Ambassade Hotel, accompanied by the tall, dark-haired woman. A moment later, the German raised his parabolic microphone and aimed it toward the third-floor window on the left side of the hotel’s façade. The Israeli appeared there briefly and stared into the street. The Swiss snapped one final picture, then watched as the curtains closed with a snap.

29

MONTMARTRE, PARIS

T he steps of the rue Chappe were damp with morning drizzle. Maurice Durand stood at the summit, kneading the patch of pain in his lower back, then made his way through the narrow streets of Montmartre to an apartment house on the rue Ravignan. He peered up at the large windows of the unit on the top floor for a moment before lowering his gaze to the intercom. Five of the names were neatly typed. The sixth was rendered in distinctive script: Yves Morel …

For a single night, twenty-two years earlier, the name had been on the lips of every important collector in Paris. Even Durand, who normally kept a discreet distance from the legitimate art world, felt compelled to attend Morel’s auspicious debut. The collectors pronounced Morel a genius—a worthy successor to such greats as Picasso, Matisse, and Vuillard—and by evening’s end every canvas in the gallery was spoken for. But that all changed the following morning when the all-powerful Paris art critics had their say. Yes, they acknowledged, young Morel was a remarkable technician. But his work lacked boldness, imagination, and, perhaps most important, originality. Within hours, every collector had withdrawn his offer, and a career that seemed destined for the stratosphere came crashing ignominiously to the ground.

At first, Yves Morel was angry. Angry at the critics who had savaged him. Angry at the gallery owners who then refused to show his work. But most of his rage was reserved for the craven, deep-pocketed collectors who had been so easily swayed. “They’re sheep,” Morel declared to anyone who would listen. “Moneyed phonies who probably couldn’t tell a fake from the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher