![The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)]()

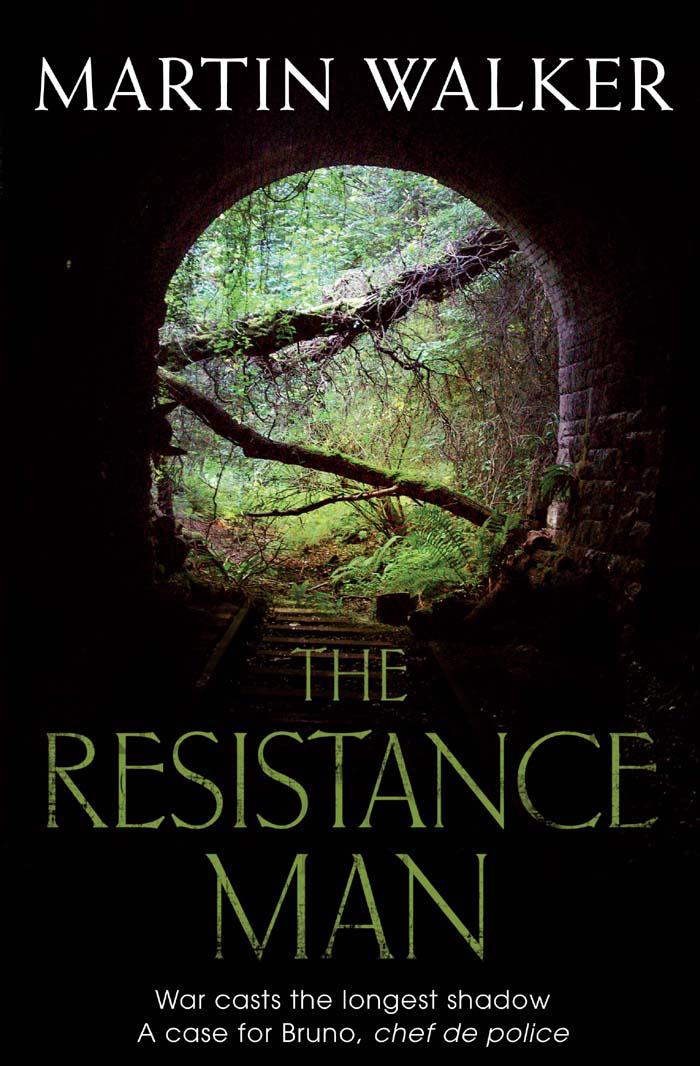

The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)

follow-through after the forehand drive had slammed her precious laptop into his temple. The sheer metallic case cracked open and components and letters from the keyboard tinkled to the floor.

‘Thank you,’ Bruno said, his legs still trembling and his mouth dry. Painfully, he swallowed and bent to collect the pistol that had fallen from Brian’s hand. ‘We’ll get you a new computer.’

Florence let out a great sob, threw down the wrecked computer, put her hands to her face and crumpled into Bruno’s arms.

‘Can you please take me home to my children?’ she asked him as J-J handcuffed the unconscious man.

Bruno led her out, leaving J-J and the rest of them to clear up, complete the paperwork and file the charges. He settled her in the passenger seat of his Land Rover and called the Mayor.

‘It’s over. Paul is dead, shot by Brian Fullerton, who has now been charged with the murder of his brother. No hostages hurt. I’m taking Florence home to her children. If Paris calls, tell them it’s all ended well. If Pamela calls, tell her I’m on my way. I’ll see you tomorrow.’

Bruno rang off, feeling a great wave of tiredness that slowed him as he climbed behind the wheel and set off back to St Denis. He thought of Yves and the way he’d spoken of his daughter, Odile. He thought of the murdered Francis Fullerton and his yearning to be a father. He felt himself groping to understand these deep and potent tides of parenthood andfamily, the waves of ancestry and succession that tied past and present together.

He looked at Florence, aching to be back with her children, and he thought of the risks he had taken that evening. And he wondered if he’d ever have stepped into such danger if Isabelle had still been carrying his child.

Acknowledgements

This is a work of fiction and all characters, places and institutions are inventions, except for the historical facts cited below.

The Resistance train robbery at Neuvic in July 1944 took place exactly as described here, and the haul was 2,280 million francs. The final months of the war were a period of sharp inflation, so comparative values are difficult to establish, but the exchange rate calculated for the US Federal Reserve by the US Embassy in Paris in 1945 suggests that the sum taken was around 300 million euros in today’s money, or $400 million. See: www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/rfd/1946/47/rfd47.pdf

In financial terms, it was by far the greatest train robbery of all time. In suggesting that this was five times the national budget for education, I used the best detailed analysis of the French state budget for 1946, which can be found online at: www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/pop_0032-4663_1947_num_2_4_1873

I am grateful to my friend Jean-Jacques Gillot, an eminent local historian and co-author of

Résistants du Périgord

, an authoritative encyclopaedia of the Resistance in Périgord, for his invaluable researches into the Neuvic affair. He generously shared his archives with me, including those of the

Paix et Liberté

movement, a shadowy anti-Communist group withaccess to police archives which was set up after the war to monitor the French left, apparently with clandestine US support. M. Gillot is also the author of the best account of the fate of the Neuvic money,

Le partage des milliards de la Résistance

, and of

Doublemètre

, an enthralling account of the Resistance leader Orlov, almost certainly a Soviet spy, who suddenly became exceedingly wealthy after the war. So did many others, including André Malraux, and despite repeated official inquiries, the fate of much of the Neuvic money remains unknown.

The use of the Marshall Plan slush-funds to finance US intelligence operations in Europe after the war is a matter of historical record. My own book,

The Cold War: A History

(London and New York, 1993), covers much of the ground. Preventing a Communist takeover in France and Italy after 1945, when the Communists were the largest and best-organized of all political parties, was a top priority for the US and Britain. George F. Kennan, the career US diplomat whose famous Long Telegram from Moscow in 1946 sketched out the grand strategy of containment that was to guide US policy throughout the Cold War, argued for US military intervention if the Communists looked like winning power through elections.

My account of Jacqueline’s researches into secret US assistance to the French nuclear programme after 1970 is historically

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher