![The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)]()

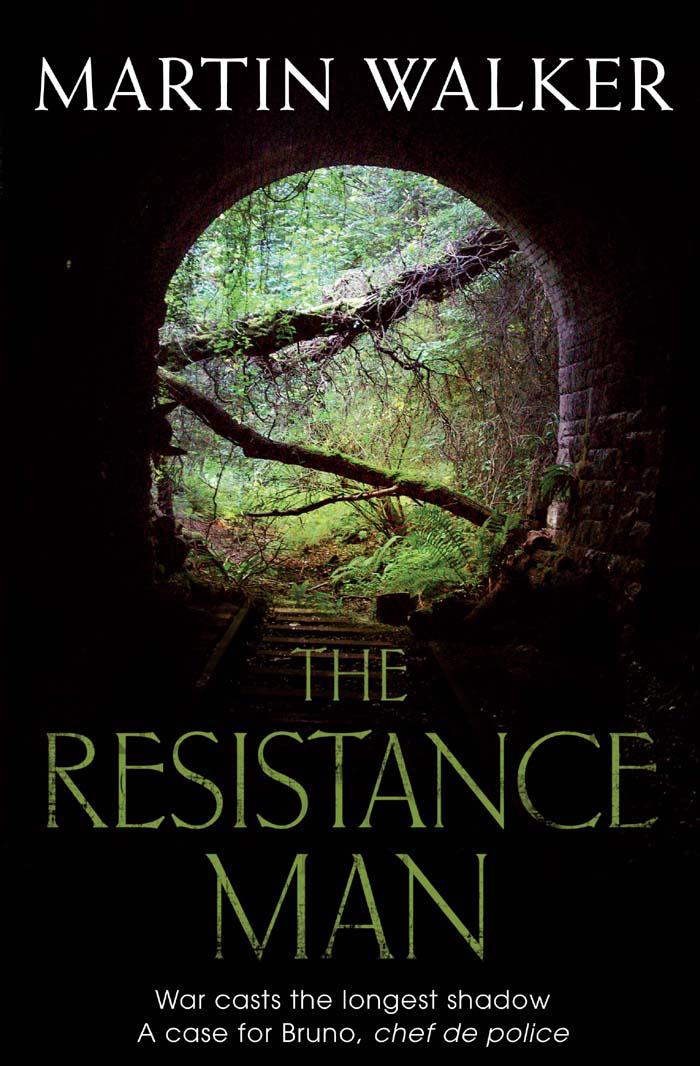

The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)

appeared to have been taken with a cell phone. One was of Yves Valentoux and Francis Fullerton standing together, eyes only for each other, at a bar. On a counter behind them was the kind of beer glass, a dimpled jug, that you only found in English pubs. The second photo was in the same place and showed the two men kissing. Was this the trigger for Paul’s jealous rage? Who might have sent it, and with what motive?

Most of the mail was junk, but he found an insurance form for the white van, a pharmacist’s receipt for eighty-three euros that had not yet been claimed back from the

mutuel

, the health insurance fund of the transport employees section of the Force Ouvrière trade union. Finally he found a bank statement that showed Paul with just over two thousand euros in his account. The address for the account was the bar downstairs.

‘No more,’ said the woman, and made no objection when Bruno took the papers. She followed him upstairs, and by the time he was at the door she was mopping the floor again. He suspected her boss would never learn of his visit. He left messages for both J-J and Jofflin to pass on Murcoing’s old address and to suggest that a visit to Marcel’s bar might produce some leads. Since he was in Bergerac he looked up the address he had for Joséphine, Murcoing’s aunt. She worked with old people, Father Sentout had said. She lived not far from the first tattoo place he had visited, a crumbling neighbourhoodwhere the butchers advertised halal meat and several of the women were veiled.

She answered the door in a housecoat with a towel wrapped turban-style around her head and flapping her hands in a way that suggested she was drying her nail polish.

‘I’ve come to give you fifty euros,’ he said, showing the banknote.

‘I thought you’d pay me at the funeral tomorrow.’

‘I was nearby so I thought I’d deal with it now. You might be busy tomorrow. If you’ll just sign this receipt for two of your father’s old banknotes, one for the

Mairie

and the other for the Resistance museum, and I’ll be on my way.’

She invited him in, offered a cup of coffee, and as her kettle boiled she glanced casually at the receipt he’d brought and pocketed the fifty euros. Bruno had drafted the receipt with care, saying that the sum was received ‘in return for two invalid banknotes of a thousand francs, dated 1940, said notes to be used for historical display only’. The space to be signed and dated by Joséphine identified her as representing the lawful heirs of Loïc Murcoing.

She sat at the kitchen table to sign it, and made no objection when he pulled out a chair and joined her, resting his arms on the slightly sticky waxed tablecloth. The kitchen looked as though it hadn’t been changed for decades. There were none of the usual fitted cupboards, but racks of shelves for the plates and a small refrigerator that growled and wheezed. Joséphine wrote clumsily, as one not much accustomed to writing, and then turned aside to make the coffee, grinding the beans and then using a cafetière. It was good and he said so.

‘I’m never one to scrimp on a good cup of coffee,’ she said, adding three lumps of sugar to her cup. ‘One of my only treats these days.’

‘Everybody in the family coming to the funeral?’ he asked.

She eyed him narrowly, her hand sliding down to the pocket of her housecoat as if to make sure the banknote was still there. ‘I’ll say this for you, you’re the first copper who didn’t push his way in and start asking where I was hiding Paul. And before you ask, I don’t know where he is and nor do my sisters. And nobody will be more surprised than me if he shows his face at the funeral and gets arrested.’

‘I heard he was living over a bar near the centre, a place called Proust, known to the customers as Marcel’s.’

‘You know more than the coppers round here then. He was supposed to have part-ownership of that place, but I don’t know what came of it. Probably nothing, like most of Paul’s big ideas.’ The words were harsh but her tone was fond, Bruno noted.

‘He seemed a bright lad from what I hear, someone who should be going places rather than just driving a van.’

‘His grandpa was so proud of him, always top of the class,’ she said. ‘We all were when he passed his

Bac

and went off to the university, first time anyone in our family ever did that. He was always clever, but a sweet kid. Everybody liked him, even animals. He always

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher