![The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)]()

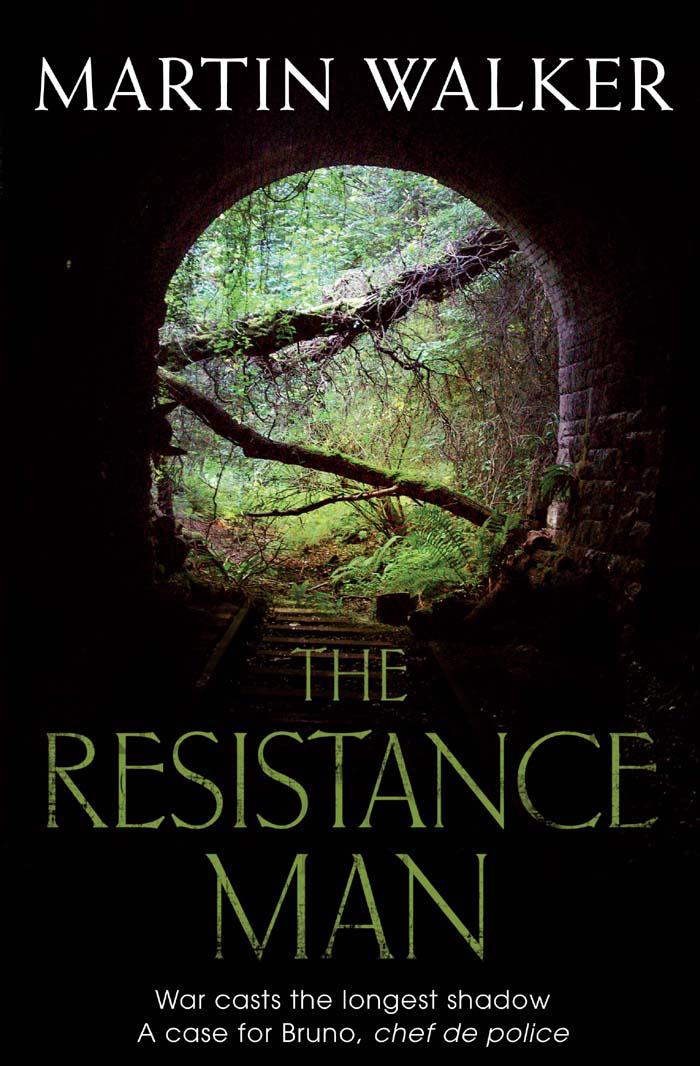

The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)

had one in tow, a dog or a cat. He had a way with them, stray dogs used to follow him home. He always wanted to keep them but his dad had walked out soon after he was born so there was no money.’

‘He did well to get to university,’ said Bruno.

‘That’s when it all went wrong. He was easily led astray was Paul, fell in with the wrong sort, and that’s why he droppedout. I blame those damn drugs, or he’d really have made something of himself.’

‘What did he study?’ Bruno was happy to have got her talking. He still didn’t feel he knew much about Murcoing.

‘He was specializing in architecture. He could always draw beautifully, even as a little boy. Portraits, landscapes, he had a real gift. He drew one of me and I didn’t even know he was watching me. It was so good I framed it, look.’ She heaved herself to her feet, went into the sitting room and brought back a cheap plastic frame. The pencil sketch it contained was not simply recognizable as her, but it conveyed something of the determination with which she had endured a hard and ill-paid life.

‘That’s very good.’

‘He was only fourteen when he did that. You ought to see his landscapes, ones he did when he was a bit older.’ She gestured to the kitchen wall behind Bruno and he turned to look at something that had not registered when he first glanced around the kitchen. Now that he looked more carefully he saw a framed watercolour of a Bergerac street scene in autumn, leaves turning brown and the stone of the buildings merging with the grey sky. It felt sympathetic rather than gloomy, an attempt to find some beauty in a drab scene.

‘He could make a living at this.’

‘He made a few francs in the summer, doing sketches of tourists down by the statue of Cyrano, but they wanted quick caricatures, not the little portraits he liked to make. Come and look at this.’

She led him back into the sitting room, dominated by an elderly three-piece suite around a TV set, and from the cupboardbeneath the TV she drew a thick sheaf of paintings, all sketches in pencil or chalk and some more watercolours. Bruno leafed through, thinking of the waste of talent that Paul’s life represented. There were a couple of scenes of Périgord villages and churches that he’d have been proud to own, and some more fine portraits. He stopped at one that looked familiar and he suddenly realized that it was Edouard Marty as a grown man in his late twenties. There were three exquisite portraits of Francis Fullerton, one dozing in a summer hammock, another in a formal pose in a chair, and a third on a beach-front, hair ruffled by the wind. There was an intimacy about them, a depth of affectionate knowledge that suggested love.

‘He’s really gifted. I wouldn’t mind buying some of these from him, or from you maybe.’ He pulled out a watercolour of a river scene and another of a Périgord village. ‘If I gave you the money, I know you’d see he got it eventually.’

‘Give it him in prison, you mean, once you buggers round him up?’ The moment of shared appreciation had gone and Joséphine was back in her defensive stance.

‘I’d forgotten about that, I just like the paintings,’ he said, genuinely. Her glance softened.

‘He used to charge twenty, thirty euros down at the statue. Give us fifty and you can have ’em both.’

23

This time his police uniform ensured that Bruno was shown directly to Pamela’s room in the hospital. Fabiola’s phone call with the good news had reached him as he was leaving Bergerac. Pamela was awake and lucid; the scan had shown no lasting damage beyond a broken collarbone and two cracked ribs. The tubes and wires had all been removed. She was sitting up with one arm in a sling, reading an English newspaper with a pen in her good hand, when he poked his head around the open door. He gave her the overpriced flowers he’d bought at the hospital shop.

‘They’re lovely, Bruno, thank you,’ she said, returning his kiss. She tasted of toothpaste and there was a scent of lavender he’d not known her to wear before. She filled in one of the clues in her

Times

crossword before continuing. ‘Fabiola was here earlier and told me about Bess. It’s very sad and I’ll miss her, but she was an old horse and you obviously had no choice.’

‘When will they let you go home?’ There was a rather battered metal vase on the cupboard. He filled it with water from the tap.

‘Maybe tomorrow, the doctor said, since

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher