![The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)]()

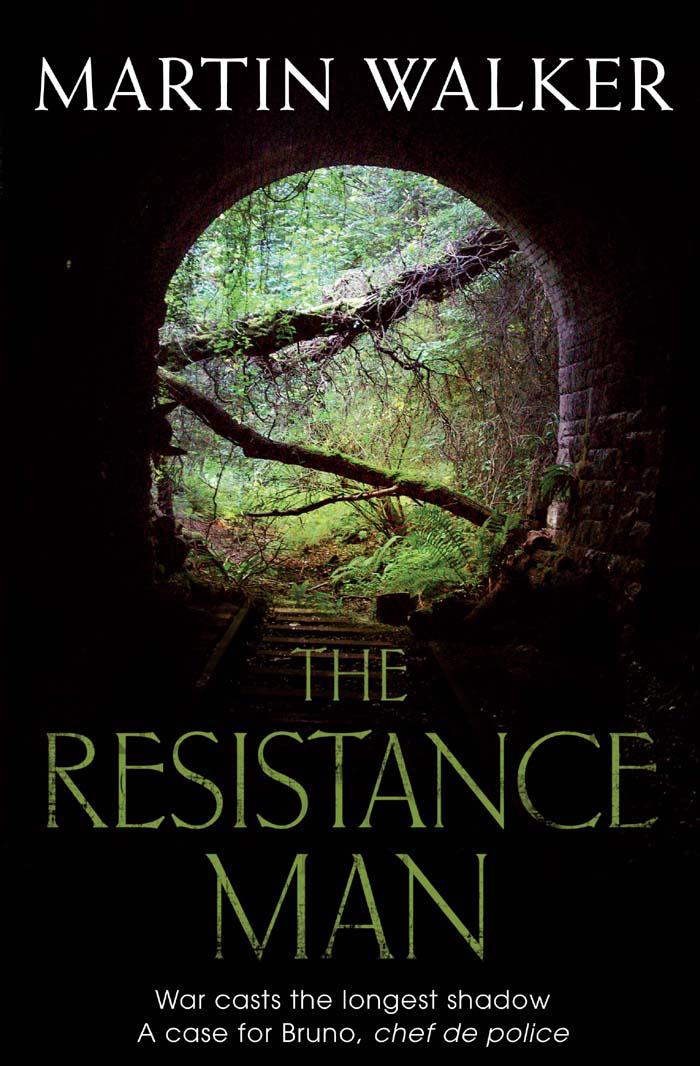

The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)

your fake email address,’ Bruno said. ‘And then you arrange a meeting. What do you suggest should happen then?’

‘I assume we can arrange the meeting at a place where you can organize a police ambush.’

‘We know he’s armed and dangerous and he’s already killed once. I don’t think you should be anywhere near the meeting place,’ Bruno replied firmly.

‘I hope you’re not planning to be involved yourself, Bruno,’ Florence said. ‘This is a job for a specialist police unit.’

‘Of course, you’re right,’ Bruno said. ‘What worries me is that we may be underestimating Murcoing. He’s no fool, and he must be suspicious of something like this falling so conveniently into his lap. I’m not sure he’ll just come waltzing to some prearranged meeting spot. If he takes the bait he’ll tryto set up a meeting at a place he can control and he’ll certainly check it out beforehand for any sign of an ambush. That’s what I’d do. Still, we may be lucky. Filial piety may bring him to his grandfather’s funeral tomorrow, which would save us all a great deal of trouble.’

The sommelier brought the decanter with the red wine Crimson had ordered, laying the cork beside it so Bruno could make out the stamped capital letters that spelled out Château Haut-Brion.

‘

Le quatre-vingts-quatorze, Monsieur

,’ murmured the sommelier, a man who had learned his art in the old school. Instead of pouring some wine for the customer to taste, he poured a tiny sip for himself and then sniffed and tasted it to pronounce it good before half-filling the three glasses.

The ninety-four, thought Bruno, a wine made when he’d been dodging mortar bombs in Sarajevo, when Paul Murcoing had been a young teenager and Francis Fullerton had been attending funerals in New York of friends who had died of AIDS. Crimson had been doing whatever the interests of the British crown required and Florence had been at school amid the dying coalfields of northern France.

Bruno’s eye was caught by a movement at the far side of the garden, where two diners had been hidden by the trees, and he was only a little surprised to see Gilles offering his arm to help Fabiola rise from her seat. The couple then strolled hand in hand from the garden and out into the night. Well, well, he thought, sniffing again at the wine and thinking that if Fabiola had been at school when it was made, Gilles had been darting across Sniper’s Alley in that same wretched Bosnian siege that he had known. Curious, thestrength of the bond that such a shared experience could forge, and it left him confident that his dear friend Fabiola was in good hands.

25

Bruno was always proud of his town, but he felt an extra glow as he stood at the big wooden doors of St Denis’s church greeting the steady flow of mourners arriving for Murcoing’s funeral. Some he had expected, like his friend the Baron wearing his medals from the Algerian war, and Joe, Bruno’s predecessor as the town policeman. Joe wore in his lapel the small red rosette of the

Légion d’Honneur

, awarded for his boyhood exploits as a Resistance courier. Then came those inhabitants of the retirement home who could still walk; they always enjoyed a good funeral, if only to remind themselves their turn had not yet come. What Bruno had not expected was the turnout of youngsters. He assumed at first it was because of Florence, their favourite teacher, in the choir. Then he saw Rollo the headmaster bringing up the rear.

‘I thought it made a good teaching moment,’ Rollo said, shaking hands. He spoke over the slow, sad tolling of the church bell. ‘We held a special lesson this morning on the history of the local Resistance for the senior classes and then asked if any of them wanted to join me at the funeral. I’m proud of them, not one stayed behind.’

Crimson murmured: ‘No reply from Murcoing yet,’ as he arrived with Brian Fullerton, followed by Monsieur Simpson,the retired English schoolteacher who had been called up in the closing weeks of the Second World War and thus counted as comrade-in-arms of the dead man. He was flanked by the only two other citizens of St Denis who could claim the honour, Jean-Pierre and Bachelot, one a veteran of the Gaullist Resistance and the other who had fought for the Communist FTP. After a lifetime of enmity which had made their families the Montagues and Capulets of St Denis, they had finally in old age and retirement become friends.

Jacqueline arrived

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher