![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

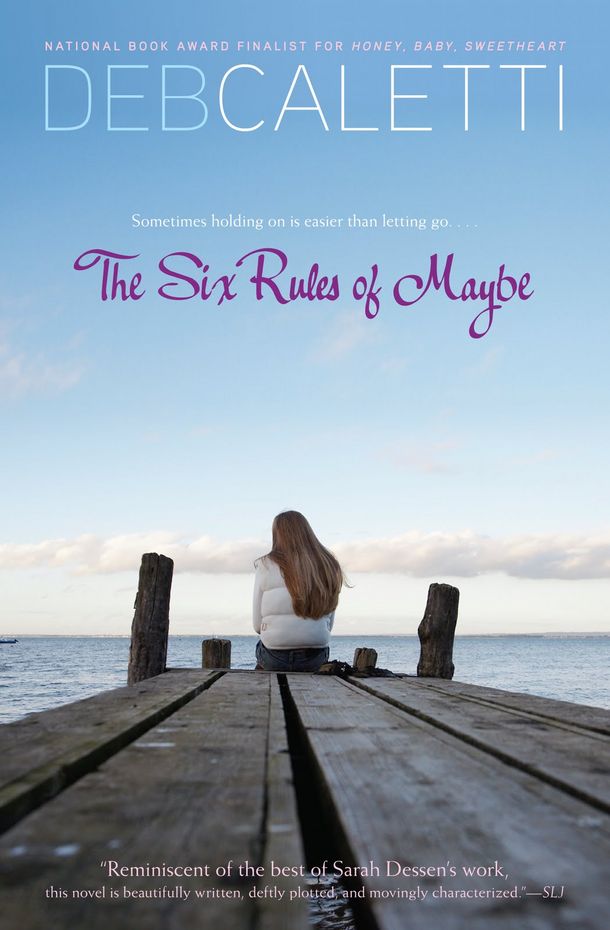

The Six Rules of Maybe

Kevin Frink didn’t belong there with Mom’s pots of tomatoes and the bird feeder (which needed filling) and the pile of our sandals next to the back door. He brought the pieces of a different life. His mom drove a hearse and they lived in a house where the curtains were never open and the roof was green with a thick layer of moss. He had body odor. We had lotions that smelled likepomegranate.

His eyes shot to our tree, to the noise of a squirrel scratching along a branch. Then, they were back to mine again. “We’ve got to break her out of there,” he said. “You go over, okay? Pretend to ask her somewhere. Shopping. Coffee. Who gives a shit. She goes with you …”

“What do you mean, break her out of there?” He seemed to think I was following along with him inside his head.

“She’s not supposed to leave. Fiona. Especially not to see me. It’s bullshit. She’s eighteen .”

“They can’t keep her prisoner.”

“Exactly. Jesus, it’s hot.”

He wiped the sweat from his face with the back of his arm. I pictured Mr. and Mrs. Saint George keeping Fiona locked in her room until she agreed to go to Yale, bringing her sparse meals on metal plates. I had a vision of stone walls, like in medieval prison movies. Then again, they didn’t seem that horrible. Mr. Saint George would bring in Clive Weaver’s garbage cans for him. Mrs. Saint George grew geraniums. They both were scientists over at the Marine Science Center. I doubted you could be too cruel if you studied sea life. “So, why did they ground her exactly?”

Kevin Frink picked at the plastic around the edge of our table. “It was dumb.”

I waited.

“You don’t need to look at me like that,” he said. “Big deal. My mom caught us in the back of the hearse.”

I’d never seen the back of a hearse, but my mind flashed a series of pictures. Maroon carpeting, quilted satin, a single creepy, curtained window. The slick bottom of a casket, slid inside. Kevin Frink’s big white whale flesh. I shuddered.

He stared at me. “For God’s sake, no one was in there,” he said. “It’s just a car .”

I didn’t want to help him and Fiona, not at all. Not anymore. I felt a little sick, from the sun and hot heavy air and from my intentions, which seemed right then stupid and innocent. They had gotten away from me, had become something else. All of my intentions had. The thing is, you open doors, but you never necessarily know what will come through them.

I wanted to back out of my actions, to sneak away in guilt, the same as that time I once knocked over a container of yogurt in the grocery store when I was maybe ten, leaving a splotch of white on the linoleum floor that I didn’t tell even my mother about. “I can’t do what you want,” I said.

“We just need to get her out of the house. That’s all. That’s all I’m asking.”

“What then?” I was afraid to know.

“She doesn’t want to go to Yale. She said she wasn’t even sure.” The high whine of a saw started over the back fence, and Kevin pulled at his ear distractedly as if the pitch bothered him. The radio started up. Do you re-mem-ber … The twenty-first night of Septem-ber … “Fucking Earth, Wind & Fire,” he said. “My mom listens to that shit.” He flicked the nail of his middle finger with his thumb over and over again. Click, click, click.

I wanted to say that not being sure about Yale wasn’t the same as not wanting to go at all. I wanted to say that I was sorry for leading him into a place he wasn’t really ready to be in. And that I was sorry too for abandoning him now in that place. But I didn’t say any of those things. “I can’t, Kevin.”

“You’re kidding, right? I thought you were my friend. I thought I could count on you.” He kept flicking that nail. It was making menervous. I wanted out of there. No, I wanted him out of there. This was my place.

I was quiet. I felt that thick curl of guilt again, the one that got in the way whenever there was something I most needed to say. “I am your friend,” I said finally.

“Whatever.” He headed for the gate. He stopped the nail thing, but he was shaking his head.

“Kevin.”

“What ever .”

The gate slammed behind him, and the latch shut with a clatter. The smell of him hung around a while until it, too, decided to go.

I stood there in the backyard among cheerful things—Mom’s watering can, the doormat with the sunflowers on it—and I listened to Kevin Frink step on the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher