![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

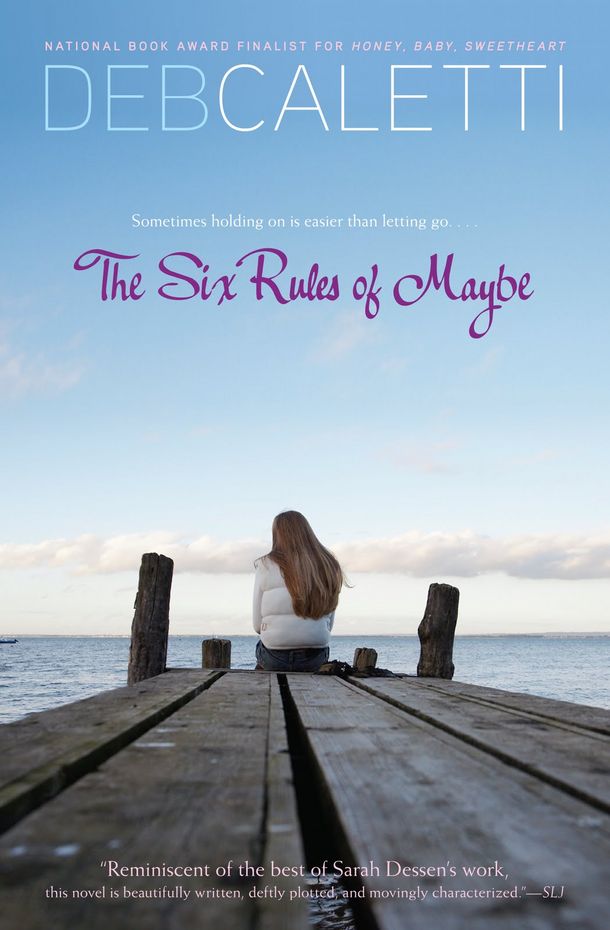

The Six Rules of Maybe

she was smiling.

“Love that baby,” Mom said. “ Love that baby.”

“That’s what Hayden says every morning,” she said. She was practically glowing.

If happiness shouldn’t make you so miserable, misery shouldn’t make you so happy.

That Sunday morning, I tried to call Nicole, but she didn’t answer. I tried again. I was beginning to act as desperate as Juliet with Buddy Wilkes.

We stayed in our robes too long that day, past the point of luxury and into the territory of self-disgust. We were all restless and edgy until finally everyone found a place to settle—Juliet took a nap, and Mom got out her scrapbook materials, something she hadn’t done in a long while. She sat cross-legged on the floor and spread out images of Beijing and Darjeeling and Trinidad on our coffee table, studying them with her head tilted to one side as she drank a cold beer. Even Clive Weaver had decided on something—he had taken Corky on a rare walk, letting Corky lead, as always, meaning they were then unwinding themselves around one of Mr. Martinelli’s rosebusheswhere they had become tangled.

Hayden had taken over my job and mowed the lawn, and as I laid on my bed and read, I had the full summer experience through my window—the sweet new odor of cut grass mixed with warm sun and the smoky, rich smells from someone else’s barbecue, set against the background music of a baseball game in the field a few blocks over and the tinkling notes of “The Entertainer,” coming from psycho Joe’s ice-cream truck.

The lawn mower stopped and started up again in the back. I wished we were having whatever those people were barbecuing. The construction men weren’t working on the weekend so there were no construction sounds, no radio Old black water, keep on rollin’, Mississippi moon won’t you keep on shining on meeee . I did hear the lumbering of a big vehicle out front and a bit later, Mr. Martinelli’s voice talking to another man. I couldn’t see either of them, just heard two voices and saw two old RVs parked next to each other, the Pleasure Way and some other big prehistoric beast, with a license plate that read CAPTAIN ED . Mr. Martinelli boasted about the GPS System and the Ample Storage but Captain Ed must not have been impressed enough, because he drove off a few moments later, leaving Mr. Martinelli silent.

That’s when the blast came. It was an explosive shot, a fierce crack and crash and shatter that I felt through my whole body. There was the clattering of glass, raining down like hail. A few pieces landed right next to me on my bed, one on the very page of Psychological Diagnosis by Dr. Gerald Drinksmore. I flew to my feet. My heart was pounding hard, hard, hard. Jesus, what had happened? There was a jagged hole in my window, right in my own window , glittering glass everywhere, a plastic rocket on my floor.

“Scarlet!” Mom yelled. I heard her racing up the stairs.

“I’m okay,” I yelled back.

I looked outside. I could see Jeffrey and Jacob there, staring back up at me. “Dad said to wait ,” Jeffrey said.

Ally Pete-Robbins dashed into the street, her blouse buttoned wrong. “What have you done?” she yelled. She looked up, saw me standing there. “Are you all right?”

“Everyone’s fine,” I called down.

“Dear Lord, you could have hurt someone! You’re lucky no one was hurt!”

Mr. Pete-Robbins came running out next. His hair was messed up, and he was shirtless. “Boys!” he said in a father voice.

“You coulda poked someone’s eye out, Jacob,” Jeffrey said.

Hayden covered the broken window with cardboard and duct tape until it could be repaired, but you could still feel a draft of cool air from the opening. It reminded me of the dreams I had sometimes, when a puncture would appear in the side of an airplane I was in, sucking things out.

I could hear everything outside as if there were no barrier between me and anyone else, none. I shot awake when the milk truck came the next morning—it sounded like it was driving right up to my bed, and while I was getting dressed later on, the voices of a couple and their small children and Yvonne Yolanda barged right in and made me cover up, fast. I hadn’t understood the importance of that sheet of glass before, or even the screen, how necessary a barrier was. Even the thinnest and most breakable boundary was better than none. But now, with only cardboard, I was open and exposed to whatever might happen.

I worked the cash

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher